Politics

What makes some people not vote

Experts point to factors like geography and elected representatives disappointing voters.

Purushottam Poudel

Voting is a fundamental right of every adult citizen. But if we look at turnout figures from Nepal’s last two elections, around 35 percent of registered voters, on average, do not cast their ballot.

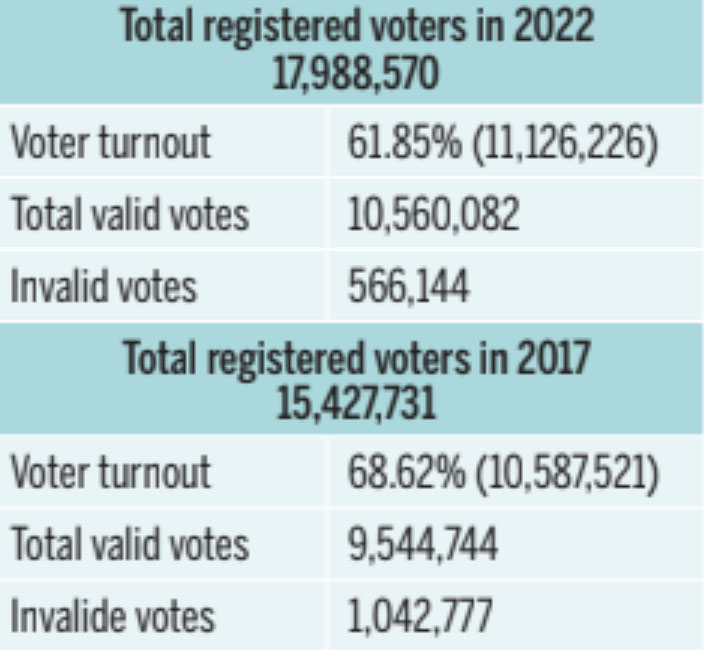

According to the Election Commission, registered voters for the 2017 federal elections totalled 15,427,731. Among them, 10,587,521 people participated in the voting process while only 9,544,744 votes were valid. The voter turnout was 68.62 percent.

In 2022, there were 17,988,570 registered voters and 11,126,226 people turned up at polling stations. Among the ballots cast, 10,560,082 were valid while 566,144 were declared invalid. This accounted for 61.85 percent voter turnout.

Despite having 2,560,839 more registered voters, voter turnout in 2022 fell 6.77 percent from the 2017 percentage. Nearly a million new voters have registered themselves this time following the Gen Z uprising of September.

Former election officers deem a voting percentage above 50 percent good, especially in democratic countries where elections are regularly held.

In the 2024 US presidential election, around 64 percent of voters cast their ballots. In neighbouring India, the 2024 Lok Sabha election saw 65.79 percent voter turnout.

Still, an oft-asked question is—why do so many people not care to vote when it’s not just their fundamental right, but also a duty?

Former Chief Election Commissioner Bhojraj Pokhrel says voter turnout in Nepal should be considered comparatively low considering the number of registered voters. In remote hilly regions, difficult geography makes it impossible for everyone in a household to take part in the elections. As a result, after managing household responsibilities, it is often only one family member who goes to cast a vote.

In urban areas, voters face different kinds of problems. Shankar Khatiwada, a permanent resident of Okhaldhunga who currently lives in Kathmandu, says his job is the reason why he won’t be able to vote in the March 5 election.

Though there were discussions on allowing inter-constituency voting this election, it did not materialise because of “resource constraints” of the Election Commission. Failure to ensure this adds to the voters’ burden.

“Going home and coming back after the election period would cost thousands of rupees,” Bijay Ghimire, a 34-year-old hailing from Madi in Chitwan-3, told the Post. “At a time when the economy is sluggish, I cannot afford such unnecessary expenses.”

Ghimire, who runs a business at the National Business Trade Centre (NBTC) in Kalanki, says he won’t be taking part in this election. Due to his business commitments, it is not possible for Ghimire and his family members to travel home for the vote. Ghimire lives in Kathmandu with his joint family and admits that he has not even made a voter identity card.

Despite constraints, the interest in voting is generally stronger in rural areas than in urban places, former election commissioner Pokhrel told the Post. “This is not unique to Nepal. In other countries as well, people living in cities tend to be less inclined to participate in the voting process.”

Pokhrel agrees that the absence of inter-constituency voting discourages some people from exercising their franchise. In addition, he notes that the mindset among sections of the public that a single vote does not really make a difference in the outcome also deters many voters.

Pokhrel further points out that in some parts of Nepal, women choose not to vote, deeming it unessential once the head of the family has already cast a ballot. Such attitudes, he says, lead to a lower turnout.

But for Bikal Shrestha, a researcher at the National Election Observation Committee, the main reason behind non-participation in elections is the absence of a large number of registered voters from the country. “Our study shows that most of the people in the country participate in the polls,” Shrestha said.

A large section of the country’s population has gone abroad in search of jobs and education, and the lack of a system that allows people to vote from overseas is another major factor of low voter turnout.

Even among the citizens in the country, prolonged political instability, frequent changes in government, and unfulfilled election promises have led to deep frustration and mistrust. When voters feel that the representatives they sent to parliament fail to address problems—such as lack of jobs, inflation, poor service delivery, and bad governance—they doubt whether their vote makes a difference, experts and observers stress.

Others stay away from the polls as they do not have clear choices. When political parties field candidates who appear disconnected from public concerns, or when the same faces return election after election despite their poor performance, voters could feel they are being asked to choose between equally uninspiring options. In such cases, abstaining can seem like a form of silent protest, Shrestha shared.

Poor election awareness also contributes to low turnout in the election, Shrestha added.

Narayan Prasad Bhatta, spokesperson for the Election Commission, concedes that the lack of awareness of the duty to vote also contributes to low turnout.

Adds Pradip Pokhrel, former chairperson of the Election Observation Committee Nepal: “If we look back, people of Nepal have always voted for change. But lately, in the absence of good options, people have had to choose from among the worst.”

16.13°C Kathmandu

16.13°C Kathmandu