Money

Remittance hits Rs961 billion, an all-time high in the time of Covid-19

The flow of capital from immigrants reached a record high despite labour migration dropping to a 16-year low.

Sangam Prasain

From 2020 to early 2021, the global economic crisis worsened with millions of workers losing jobs due to the Covid-19 pandemic. Like in other countries, a reverse migration started in Nepal too, with official figures suggesting that nearly half a million Nepalis who were stranded abroad were rescued, and outbound numbers plunged.

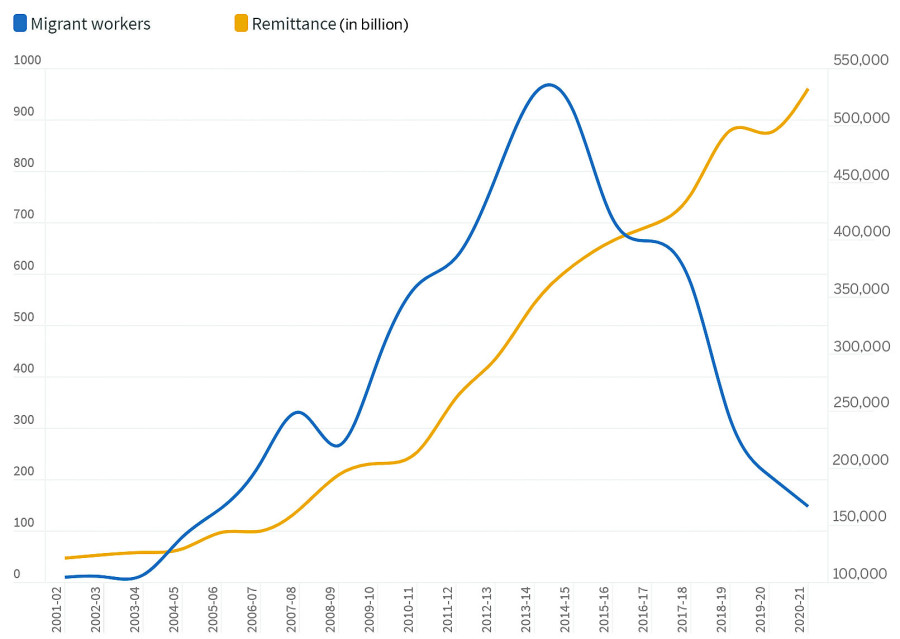

But despite an odd situation, Nepali migrant workers sent home Rs961.05 billion in the last fiscal year, ending mid-July, a record-high money transfer to Nepal since Nepalis started to look for overseas employment more than two decades ago.

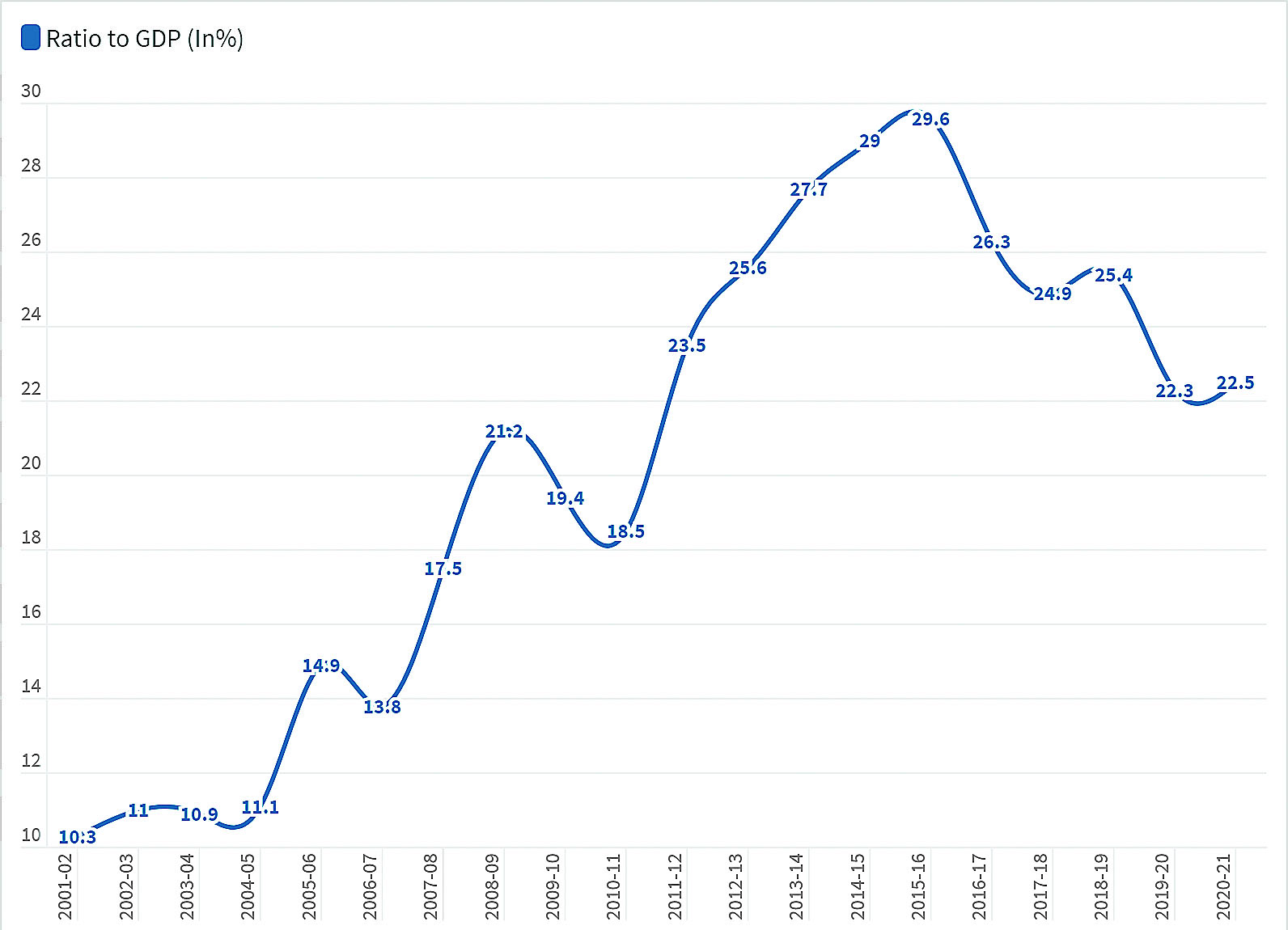

The amount grew 10 percent year on year, which is equivalent to 22.5 percent of Nepal’s current gross domestic product of Rs4.26 trillion evaluated at current market prices.

Remittance, the flow of capital from immigrants to families back home, is a crucial source of income for many countries, including Nepal.

Despite the popular labour markets in the Gulf Cooperation Council countries and Malaysia being severely impacted by Covid-19 that left millions of foreign workers with no option than to pack their bags and leave, remittance has proved far more resilient than expected.

The number of migrant workers going abroad, however, dropped to a 16-year low to 166,698 individuals.

There is a mismatch.

Economists say Nepal’s labour market indicators can broadly be divided into two types–stock variables and flow variables.

“Generally, we have an understanding that if a greater number of people go abroad, they will send home more money. But that’s not the case,” Nara Bahadur Thapa, former executive director of the Nepal Rastra Bank, told the Post.

“First after the earthquake of 2015, and now, it has become evident that we have a massive labour stock abroad, or at least 3 million Nepalis are working in different countries for years or decades. So that’s stock variables.”

According to Thapa, even though the number of migrant workers going abroad, which are flow variables, on an annual basis drops, it will not impact the earnings.

“These people did not return during the pandemic as they felt safe where they were because of the social security protection schemes of the respective countries,” said Thapa.

According to the Department of Foreign employment, the numbers of Nepalis working abroad started to increase after 2000 when the Maoist insurgency that started in 1996 was at its peak.

In the fiscal year 2000-01, just over 55,000 Nepalis went abroad. They sent home a little over Rs47 billion. With the country’s economy suffering due to the insurgency, Nepali youths had no choice.

From just 3,605 migrant workers who were given work permits in 1993-94, the numbers started to multiply, reaching as high as 527,814 individuals in 2013-14, a jump of nearly 147 times in two decades.

The remittance amount too jumped more than 11 times, reaching Rs543.29 billion in the same period. According to the department statistics, it has issued labour permits to more than 4.5 million Nepalis in the last two decades.

But the number started to drop after the government started tightening the labour sector amid reports of workers being abused in most of the labour destinations. In 2018-19, a year before the Covid-19 pandemic, the number dropped to 243,868 individuals. In the last fiscal year 2020-21, the number dropped to a 16-year low.

Despite a drop in migrant worker numbers, remittance kept soaring.

There are basically, as assumed, five different factors why the income has been inversely proportional to the number of migrant workers, according to Thapa, who also served at the research division of Nepal’s central bank.

Besides the stock variables and flow variables, says Thapa, the second factor is many countries have increased the workers’ wages significantly in the last five years and that has been reflected in Nepal's earnings.

“Thirdly, migrant workers cut their spendings on consumption, entertainment and movement due to Covid-19 related restrictions,” he said

Migrant workers returning home did not buy gold, clothes and electronic items. “The appreciation of the US dollar is also a factor to boost remittance earnings,” said Thapa.

Fourthly, the illegal funds transfer channel or hundi has been almost closed due to restrictions caused by the Covid-19 globally. And lastly, during crises, as happened after the 2015 earthquake, Nepalis living abroad send more money to support their families, basically for health.

As per the details released by the Covid-19 Crisis Management Centre, a total of 489,418 Nepalis from 60 countries have so far been rescued in the last one year and a half. Most people were rescued from labour destinations including the Persian Gulf states, Malaysia and India.

The highest number of Nepalis were rescued from the United Arab Emirates with 146,624 people repatriated from the country, followed by Qatar (117,408), Malaysia (51,459), Saudi Arabia (45,186), and India (39,541). A significant number of Nepalis were also rescued from Kuwait, Turkey and Japan. Nepal is among the countries having reverse migration on a massive scale.

According to the International Labour Organization, over 600,000 were repatriated by India and 230,000 returned home to the Philippines, where the economy depends significantly on remittances from migrant workers.

According to Nepal Rastra Bank statistics, in the last two decades, remittance earnings increased 20 times, boosting consumption and economic growth although Nepal’s economy suffered a slowdown.

A survey conducted by the Nepal Rastra Bank in 2014-15 in 16 districts comprising 320 households shows that 25.3 percent of the money received from migrant workers goes towards repayment of the loans taken by the households, 23.9 percent is spent on buying foods, clothes and other daily essentials, 9.7 percent on education and health bills, 3.5 percent on marriage and other social occasions, and 3 percent on buying assets like land.

Similarly, 28 percent goes for saving purposes and 1.1 percent for investment in business.

"Although most of the remittance is spent on consumption, it has been contributing to the health, education and uplift of the family creating a direct impact on the economy,” the survey said.

The central bank’s report says that one of Nepal's major exports is labour, and most rural households now rely on at least one member's earnings from employment away from home.

Nepali workers have sought foreign employment as both the agricultural and non-agricultural sectors struggle to generate new employment opportunities.

With limited arable land, landlessness is pervasive and the number of landless households has steadily increased in the agricultural sector. In the non-agricultural sector, the slowdown in growth, especially since 2000-01, due to the Maoist insurgency which killed more than 17,000 people further retarded the pace of employment creation, the report said.

Political unrest in the country adversely affected economic growth. According to the central bank, for most of the past decade, the economic growth rate hovered around a mere 3–4 percent, peaking in 2007-08, at 6 percent, following the comprehensive peace accord between the Maoists and the government in 2006.

Then Nepalis started to live under darkness. Between 2007 and 2017, the country went through a massive electricity supply shortage that caused up to 18 hours of daily power outages.

This load-shedding had had a dire effect on Nepal's economy. According to a World Bank report, the reliable power supply would have increased the country's annual gross domestic product by almost 7 percent, and annual investment would have been 48 percent higher. Load-shedding became another push factor for young Nepalis to go abroad.

“Obviously, due to various factors, Nepal is gradually switching to a remittance-driven economy from an agriculture-driven economy,” said economist Min Bahadur Shrestha.

The money sent home by Nepalis working abroad has played a crucial role in lifting people from the traps of poverty. Remittance income has also pushed up consumption. According to the Central Bureau of Statistics, in the last fiscal year that ended in mid-July, Nepal’s final consumption expenditure at current prices amounted to Rs3.98 trillion, representing 93.38 percent of the gross domestic product.

There are worries any significant decline in remittances could disturb the structure of the economy from the macro level.

But Shrestha does not agree. “It’s an exceptional case that the collapse of any country’s economy will hurt the remittance of another country,” he said. “We should not worry.”

However, the one thing that will hurt Nepal is that it will not reap the demographic dividend in terms of nation-building in the long term, despite more than 40 percent of the country’s population being young, said Shrestha, a former vice-chairman of the National Planning Commission.

“We are getting little but losing big,” he said.

The short-term risk, according to Shrestha, will be on trade as imports will increase drastically fuelled by remittance once the Covid-19 situation improves. “As the agriculture sector will suffer from the labour deficit, demand will be met by imports supported by remittances,” he said. “It’s a check and balance principle in our economy.”

Unfazed by the Covid-19 pandemic and resultant restrictions on movement which strangled foreign trade across the world, Nepal continued to splurge on its ever-increasing remittance inflow on imports and even achieved new highs in spending.

According to the statistics released by the Department of Customs, the country’s overall imports grew by 28.66 percent to Rs1.53 trillion in the last fiscal year. Exports, however, remained at a mere Rs141 billion. The trade deficit rose by 27.26 percent over a year.

While the number of migrant workers dropped to a 16-year low last fiscal year, experts believe that the outlook of the labour market, particularly from Nepal, is encouraging.

Jeevan Baniya, a labour migration expert with the Centre for the Study of Labour and Mobility at Social Science Baha, told the Post that the number of Nepalis going abroad, including students, will grow leaps and bounds in the near future.

“There is a huge shortage of workers in the developing and developed nations and that’s a positive sign for aspirant Nepalis who struggle their whole life in Nepal to get a decent job,” he said. “The slowed economic growth caused by the pandemic, including the political situation in Nepal, gives little hope for the aspiring young population. The only alternative for them is going abroad.”

Baniya said that even if the job market improves in Nepal, the salary or the pay is so low that even the highly-skilled manpower does not want to stay in Nepal.

“The wages in almost all labour destinations have increased significantly and it’s a big pull factor,” he said, adding that skilled workers get a starting pay of $1,000 a month in most of the labour market. “Why should one stay in Nepal then where a government secretary earns a little over Rs50,000 per month.”

According to the International Labour Organisation report released recently, jobs lost in the heat of the Covid-19 crisis will not be recovered until 2023, at the earliest.

The pandemic, which caused a shortfall of 144 million available jobs in 2020, will have aftershocks in the global labour market.

Asia will not return to pre-pandemic levels in 2022 despite enjoying the world's highest labour force participation and employment rates in the decade before the crisis.

But according to Shrestha, given the labour demand and vaccination drive in the developed countries, the labour market will recover by 2022.

“The job outlook bodes well for young people entering the labour market,” said Shrestha.

19.6°C Kathmandu

19.6°C Kathmandu