Culture & Lifestyle

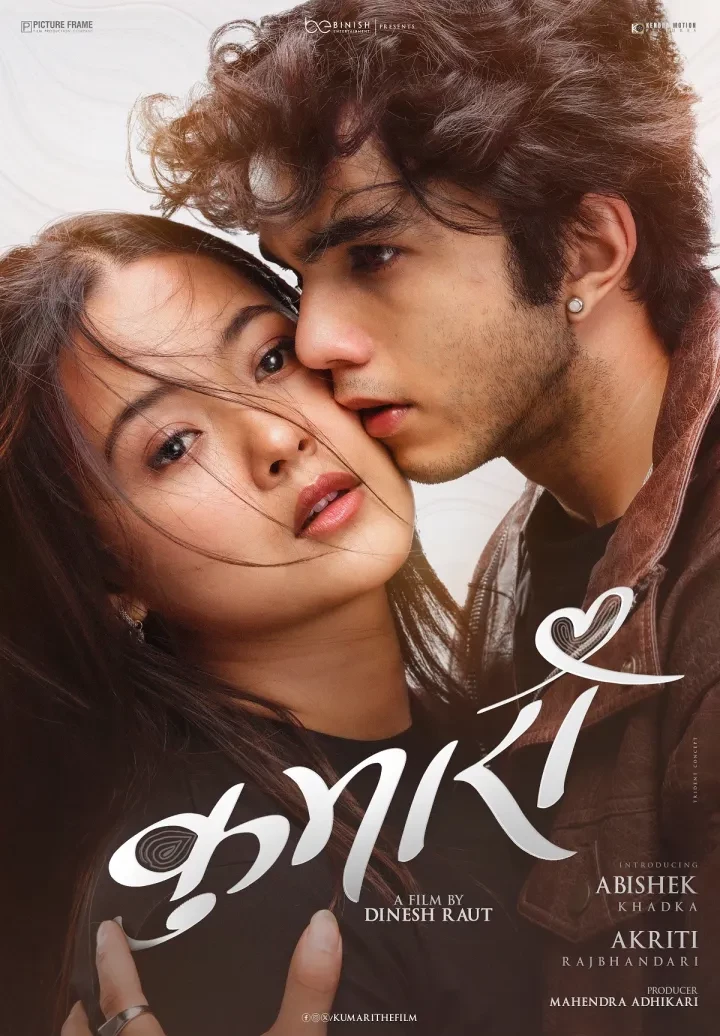

‘Kumari’: Falling in love under society’s watchful eye

A restrained romantic drama carried by sincere performances and rooted in themes of trauma and social stigma.

Sanskriti Pokharel

‘Kumari’ begins with colour and light. Isha, played by Aakriti Rajbhandari, laughs freely among children during Holi. The frame is warm, sunlit, and alive. There is ease in her smile. That sense of brightness, however, does not last long.

The film subtly introduces fear into that happiness, and from that moment onward, it becomes clear that this is not simply a love story. It is a story about memory, shame, and the social obsession with purity.

The romance between Isha and Prayag, played by Abishek Khadka, is built on familiarity. They are neighbours. Their houses face each other. He waits on the balcony, hoping he can see her. They run into each other at grocery stores and on the street. These details are undeniably sweet. The actors handle these moments with natural restraint. Their glances feel genuine. Their hesitation feels real. For two newcomers, the emotional honesty they bring to the screen is impressive. There is no exaggerated drama in their early interactions. Instead, there is awkwardness, silence, and curiosity that make the romance relatable.

At the same time, the film leans heavily on coincidence to keep them together. The repeated “accidental” meetings sometimes feel engineered rather than organic. While love often feels fated when one is inside it, cinema requires a careful balance between destiny and plausibility. Here, that balance occasionally slips. The charm remains, but it begins to feel slightly constructed.

Moreover, there is also a rescue sequence that feels instantly recognisable to anyone familiar with South Asian films. A woman is harassed, a man intervenes, and his masculinity is affirmed through confrontation. Although the scene is engaging and meant to establish emotional safety, it follows a well-worn cinematic pattern.

The real disruption arrives in a single slap.

It is a shocking moment, not because of its physical force but because of its social consequences. A girl slapping a boy in a family gathering activates a deeply gendered assumption. If she hit him, he must have wronged her. Honour collapses instantly.

This is where ‘Kumari’ begins to examine how trauma operates. Isha’s reaction is not random. It is rooted in a past the film references but never fully visualises. Having gone through a difficult childhood, she carries triggers that surface without warning.

Yet this is also where the film falters.

When showing Isha’s past, the glimpses of a foreign city are limited and abstract. There is no sustained attempt to immerse the viewer in the structural violence she endured. It feels like the filmmakers wanted the weight of the issue without fully committing to its visual and emotional depth.

Had the film invested in rendering that past with honesty and texture, the present would have felt heavier.

Where the film finds unexpected complexity is in the character of Meera, played with magnetic intensity by Akanchha Karki. Her presence alters the energy of every scene she enters. It does not feel like she is performing.

Meera is a social worker. But she is not written as a saint. And that is the film’s boldest choice.

When she attempts to falsely accuse Prayag of harassment as a strategic retaliation against his family, the narrative takes a morally uncomfortable turn.

It is a deeply unsettling portrayal.

The film suggests that even those positioned as saviours can manipulate narratives. That social capital can be weaponised. That advocacy can blur into control.

This portrayal is both risky and thought-provoking. On one hand, it challenges the tendency to romanticise social workers as flawless heroes. On the other hand, it risks reinforcing suspicion toward advocacy. What makes it compelling is that Meera is neither entirely virtuous nor entirely corrupt. She represents how power can shift, and how even good intentions can become entangled with ego, reputation, and control. The film does not fully interrogate her motivations, but it leaves enough room for reflection.

Another refreshing aspect of the film is the bond between Prayag and his uncle. Their relationship is warm, humorous, and emotionally open. In many Nepali families, young people struggle to speak about love or vulnerability with their parents. The uncle becomes a safe space. Their conversations, often over drinks, feel relaxed and authentic. He teases Prayag but also listens to him seriously. This dynamic brings emotional realism to the film.

‘Kumari’ also addresses how society treats survivors. Isha is judged not for her character but for what happened to her. Her past becomes a label. People speak of her as though she carries contamination. This portrayal is painfully accurate. Survivors are often burdened with shame that does not belong to them. The film effectively highlights how stigma can wound as deeply as the original violence.

The title itself invites interpretation. What does it mean to remain “Kumari”? Is purity physical, moral, or social? The closing narration insists that women are not flowers that wither after touch. It is an overt metaphor, but it resonates. It confronts the obsession with virginity and reframes it as a social illusion.

Technically, the film delivers mixed results. The songs are strong. They are energetic and visually appealing. The costumes and festive sequences are vibrant.

However, the product placement of a clothing brand is too obvious. It appears repeatedly and conspicuously. The marketing could have been subtle.

All in all, the film may stumble at times, but it remains emotionally present throughout. It asks difficult questions without offering easy answers, and it resists turning its characters into either victims or heroes.

_______________

Kumari

Director: Dinesh Raut

Cast: Aakriti Rajbhandari, Abishek Khadka, Akanchha Karki

Duration: 2 hours 7 minutes

Year: 2026

Language: Nepali

16.13°C Kathmandu

16.13°C Kathmandu

.jpg&w=300&height=200)