Culture & Lifestyle

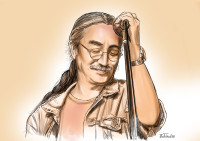

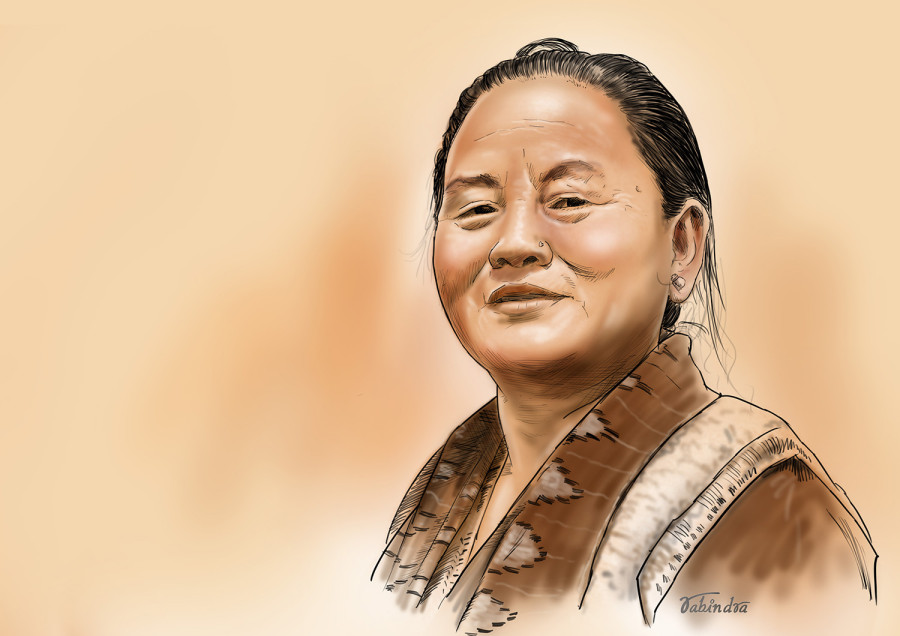

Shiva Maya Tumbahangphe: Patriarchy is structural—it is in every individual

The former deputy speaker talks about her fight for the position of House Speaker, women’s representation in politics, and patriarchy’s deep roots.

Pranaya SJB Rana

Shiva Maya Tumbahangphe is exactly how she has appeared in public in the last several weeks—articulate, no-nonsense and stern—but also prone to moments of levity, where she is funny and sardonic.

We are sitting at the Himalayan Java in Thapathali and discussing the recent controversy regarding the position of Speaker of the House of Representatives. Although she is initially hesitant to talk about what she calls a “closed chapter”, over coffee, she gradually opens up.

After Krishna Bahadur Mahara resigned in October over allegations of attempted rape, the position of Speaker became vacant and Tumbahangphe had argued that she was well-qualified to take Mahara’s place. She was not just Deputy Speaker, but also a lawyer with a doctorate degree. The Nepal Communist Party refused and asked her to step down, not realising the media storm they were about to unleash.

“Do you think I would’ve let them get away with it?” Tumbahangphe asks, before describing her fateful January 10 meeting with Nepal Communist Party co-chairs Pushpa Kamal Dahal and KP Sharma Oli, when they asked her to step down as Deputy Speaker.

“When I went to meet the co-chairs, one of them asked me when I joined the party and what I had done,” she says. “They didn’t know anything about me. I used to be a teacher so I gave them a lesson on who I was. That’s when I presented my 12-point resume.”

Tumbahangphe has long said that she was being punished for Mahara’s sins, as she had done nothing wrong. And if the House needed a Speaker, they could always have elevated the Deputy Speaker to that position. After all, the constitution says that the Speaker and Deputy Speaker need to be from different parties and of different genders.

“Comrade Prachanda called me an obstacle and I took serious issue with that. I told him that word he used was not right and I did not like it. I said that I was becoming a victim of political violence,” she recalls. “They told me that according to their lawyers, I was an obstacle. I replied, your lawyers have failed and, comrade chairman, so have you.”

Tumbahangphe wasn’t just demanding that she be made the Speaker. She had said that the moment the party decided on another candidate for Speaker, she would step down, which is why she was so offended by the co-chair’s use of the word ‘obstacle’.

“I told them I would do exactly what the constitution says. No person or position is above the constitution,” she says.

The party’s refusal to nominate Tumbahangphe for Speaker and to instead ask her to step down was met with widespread condemnation in the media and social media. I tell her about one particular comment on Twitter that basically said that Singha Durbar must be trembling at the sight of an educated, experienced, Janajati woman. She laughs and asks me to send her that comment.

She also received support from women lawmakers, but that support appeared to be partisan. Leaders from the former UML spoke out in her favour, while those from the former Maoists did not say anything.

“They definitely spoke out,” she says. “Dev Gurung, Narayan Kaji Shrestha, Devendra Poudel, Haribol Gajurel, they all spoke out. Whether they spoke in my favour or against me is another thing, but they did speak.”

On January 19, the Nepal Communist Party secretariat decided to nominate Agni Sapkota for House Speaker, and as promised, Tumbahangphe resigned as Deputy Speaker a day later on January 21.

“Let me make one thing clear, I didn’t resign because the party asked me to,” she explains. “I was not going to leave the Parliament in a vacuum so when the party decided on a Speaker, I stepped down.”

Before she stepped down, at a discussion over her book ‘Nepalma mahila andolan’ (The women’s movement in Nepal) last month, she had made a telling comment that seemed to encapsulate the entire saga: “the patriarchy appears to be even stronger than the monarchy.” I press her on that statement.

“That is just one sentence,” she says. “But inside that sentence lies the state of our society and the state of women.”

Nepal might have discarded the Ranas, the Panchayat and the monarchy but it still hasn’t been able to rid itself of the patriarchy that is ingrained in all of Nepali society. Tumbahangphe has seen this all her life, from growing up and joining politics in Taplejung and Jhapa to becoming a central committee member in the former UML.

“Forty years ago, when I was starting politics, sons and daughters were treated differently. And 40 years later, not much has changed,” she says. “I tested the patriarchy and I learned that it was as strong as ever. Patriarchy is structural and it is in every individual.”

Nepal has had a female Speaker before—Onsari Gharti Magar in 2015. That was when three of the highest positions in the state were occupied by women, with Bidya Devi Bhandari as President and Sushila Karki as Chief Justice. Many have pointed to this to refute Tumbahangphe’s argument that patriarchy was holding women down.

“That was in a different context and I wouldn’t like to comment on that,” she says. “But let’s just say that if I had a moustache, things would’ve gone very differently for me.”

Gharti Magar had her husband Barsa Man Pun, an influential Maoist leader, lobbying for her so that could have turned the tide in her favour. Tumbahangphe all of a sudden appears almost wistful that she doesn’t have any of her relatives on the ruling party secretariat that I can’t tell if she is serious or joking.

There were powerful people on Tumbahangphe’s side—President Bhandari for one, according to media reports. But Tumbahangphe rubbishes that rumour.

“If I had the prime minister and the president backing me up, would I not be Speaker?” she says. “The president is the head of state and she cannot lobby on behalf of one person. It is not considered becoming of the prime minister to lobby for one person. Those institutions should not work in favour of individuals.”

Her last remark is pointed. It is no secret that Oli was heavily in favour of Subhash Nembang for Speaker, even though it was ultimately Dahal’s choice of Sapkota who got the post.

Both co-chairs had their own men but that is no surprise to Tumbahangphe. The ruling Nepal Communist Party technically does not meet constitutional and legal requirements to be registered as a political party.

“The constitution and the Political Parties Act specifically mandates that one-third of seats at all levels of the state and the parties should be for women,” says Tumbahangphe.

This is something that women leaders in the party have long been lobbying for. The Nepal Communist Party’s 45-member standing committee includes just two women—Asta Laxmi Shakya and Pampha Bhusal—while the nine-member secretariat includes no women. In December, Shakya and Bhusal had presented a proposal demanding that the secretariat, the party’s highest decision-making body, be made more inclusive. The proposal was flatly rejected.

Even Oli’s new Cabinet, reshuffled in November, includes just two women out of 22 members.

“At the party’s ongoing central committee meeting, we spoke about women’s representation and we said that if you’re not going to ensure representation, then you need to remove that clause from the party constitution,” says Tumbahangphe. “You cannot just talk about inclusion and representation, you have to institutionalise it.”

Even the Women’s Ministry has a male minister, I say.

“That’s a good thing,” she says, before asking me whether that sounds strange to me.

“So far we’ve only trained women to speak about women’s issues but we need to change tracks and get men to speak about women’s issues as well,” she explains. “We talk about prosperity but if one half of the population is left behind, how can the nation prosper? We need to understand that women’s issues are everyone’s issues.”

Tumbahangphe is one of the rare party members who speaks so openly against the top leadership. She recently went back to her role as a central committee member of the Nepal Communist Party and there are rumours that she might be made a minister to compensate for having to step down. She doesn’t affirm or deny if that is happening. But what if the leadership, which is not known for having thick skin when it comes to criticism, decides to punish her for her public criticism?

“I’m not worried,” she says lightly. “I have many other options. In the end, it’s about working for the people and no one can stop me from doing that. But I will never stop speaking out; that’s my constitutional right.”

The entire controversy over the position of Speaker was one rare instance of an outspoken woman staking a rightful claim to a high-level position that has long been the province of men. But Tumbahangphe always said that she did not want the position because she is a woman; she wanted it because she was qualified and she deserved it. But in the end, she was denied the position because she is a woman.

“Women cannot ask for things solely on the grounds that we are women. We have to develop our capabilities first and then demand what is rightfully ours,” she says. “We need to be able to say, ‘I am as capable as any man.’”

HIMALAYAN JAVA, THAPATHALI

ON THE MENU

Cafe Latte: Rs 195

Americano Rs 150

Organic Green Tea X2 Rs 430

15.12°C Kathmandu

15.12°C Kathmandu

.jpg&w=200&height=120)