Columns

Nurturing culture and creativity

Giving creative work and culture their due would be an enormous service to Nepal.

Sophia L Pandé

Today, with global warming and mass consumption, one often feels helpless. The country is importing more than it can afford, domestic production is stalled, meaningful jobs are hard to come by, pollution is rampant, and waste is everywhere, with microplastics invading even our organs. Over 2,000 Nepalis are leaving the country every day to seek work abroad.

Unfortunately, due to outdated biases, creative and culture-related jobs are still not seen as legitimate work, though the Cultural and Creative Industries (CCIs) generate $2.25 trillion annually, which is 3.3 percent of the global GDP. The CCIs also provide employment to 6.2 percent of people around the world who are often marginalised and struggle to find more mainstream jobs.

In Nepal, investing in this nascent but vital industry must be programmed into our budget and factored into our national planning. Culture must have its own ministry for proper, well-thought-out policymaking; it can no longer be lumped into the same subset as civil aviation and tourism, though its links with the latter are inextricable.

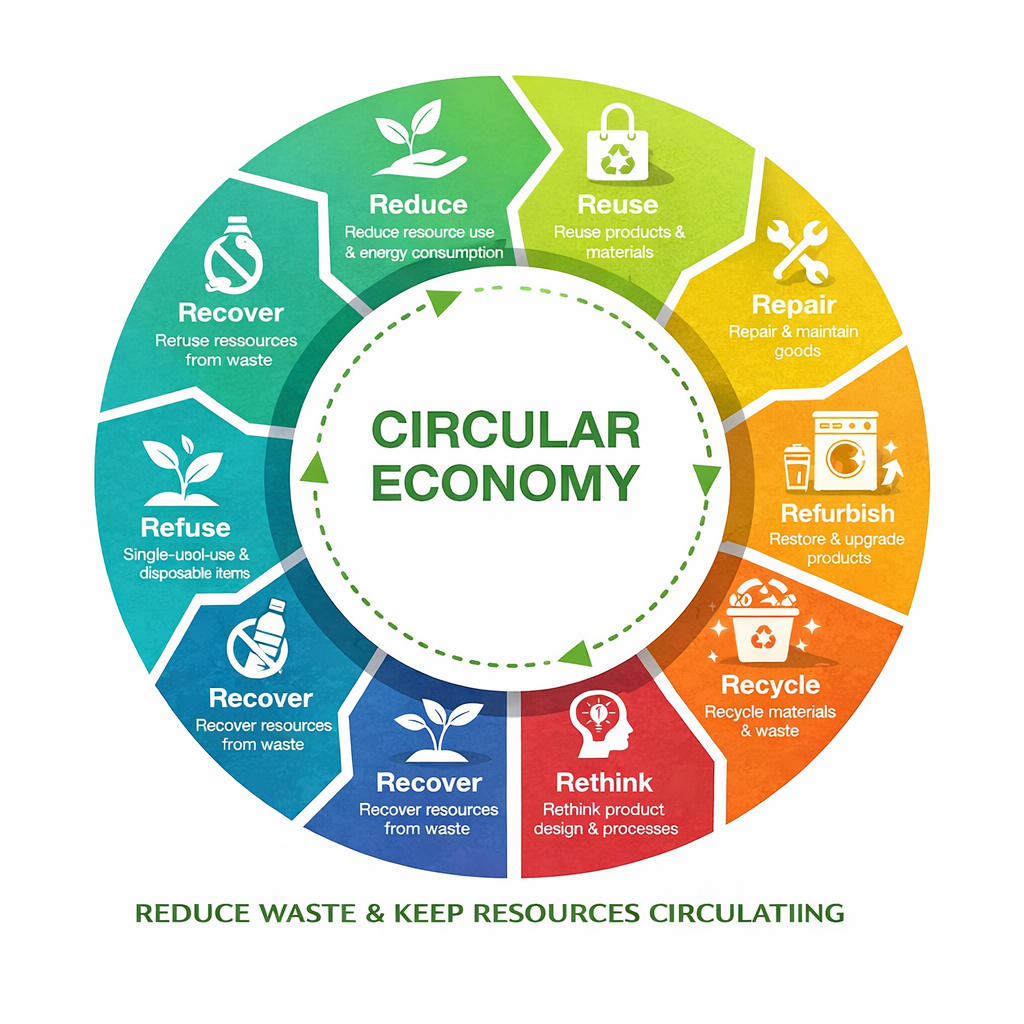

By giving creative work and culture their due, in education, in government, we would be doing a country like Nepal an enormous service, laying down a roadmap for a circular economy, with more domestic production and less waste, that will contribute towards a sustainable, equitable future for everyone.

Creativity and problem-solving are closely linked, along with thinking out of the box and working constructively while collaborating across sectors, an essential skill for development that is woefully lacking in even those with the best of intentions. Learning how to be creative and open, early on, can open up a range of opportunities for the young, allowing them to become better at life and jobs, whatever they may choose to take up.

This is why our education system needs to change, as soon as possible, from concentrating on just Science, Technology, Engineering and Mathematics (STEM) to STEAM, which includes the Arts, into what can sometimes be a very dry and rigid mix.

The strength of a balanced liberal arts education, which includes the arts, is necessary for every learner so that they can see the world through prisms and not just from one angle. Insights into disciplines aside from one’s own and openness are essential not only for good leadership but also for everyday life and a successful career.

Our existing systems are designed for those who are obviously bright and for those who work hard to succeed; they are skewed against the neurodivergent and people who float in the clouds—dreaming, living and creating in their minds. Creative fields tend to be more inclusive, not exclusive, of those who are different.

Success comes in many forms. Happiness is one of them, but it is often undervalued. The creative economy can support a more sustainable circular economy, goals we all should be working towards in today’s dying world. However, it is equally important to acknowledge that creative acts are a vital tool for nurturing the maker within us so that more people can find meaningful ways to thrive outside of the traditional nine to five grind.

UNESCO has long sought to formalise and sustain the CCIs. This past year, working together with the British Council, Finland Aid, and the International Labour Organisation, I advised on and co-wrote a long overdue, much-needed baseline survey report of the cultural and creative industries, starting with the Kathmandu Valley.

Using both quantitative and qualitative analysis, the 127 page in-depth report is soon to be published formally on the UNESCO Nepal website. This document seeks to examine the current landscape of the creative fields across the sectors of design, folk arts & crafts, film, gastronomy, literature, media arts and music.

There are many obstacles and challenges. Many creatives work informally without healthcare or pension systems, with piecemeal jobs that are often few and far between. Government funding for art and culture is non-existent, and while good governance inroads have been made in the film industry in particular, friendly policies meant to enable and encourage creativity are often stymied by bureaucratic obstinance and a lack of understanding as to their greater purpose and impact.

If proper incentives and laws were put in place, along with interventions starting at primary-level education through to vocational training, the creative economy, already coming into its own, would thrive. There is no dearth of creativity in a country like Nepal, which has a rich, varied, deep-rooted culture and a long, celebrated history of artisanship across mediums.

To invest in creativity means to buy domestically, eat locally, and encourage young and old in every aspect of their creative journey, understanding that it will help them in unforeseeable but immensely valuable ways in the future.

The tourism industry, too, has a precious, synergetic relationship with the CCIs; our local designs, architecture, artisanship, food, music, film and literature are powerful draws for the discerning tourist who wants more than just a superficial Thamel shopping experience, or a few hours at one of the durbar squares before being rushed off to their trek or jungle safari.

In the coming columns, we will explore how culture and creativity are key pillars for a sustainable economy, even as they contribute to social and political equity for those who have long practised them without the benefits of recognition.

I will end this first column on the subject with a concrete example from my own experience as a creative practitioner. Growing up in Nepal, educated at St Mary’s and Budhanilkantha School, I had no creative training. I could memorise almost anything, but I couldn’t figure out problems on my own.

Thanks to the IB programme, which I went on to, which underscores a liberal arts philosophy, I could break away from just a STEM concentration. I realised, to my horror, that I knew nothing about our own remarkable, innovative, versatile, resilient cultural heritage in Nepal.

I became fascinated with images and the history, religion and philosophy behind the arts, going on to an MFA in film production at the Tisch School of the Arts, in New York University.

While I am no longer a practising filmmaker, my creative studies taught me how to think critically, how to flesh out ideas from end to end, how to analyse and defend my stances, how to plan projects rigorously with immense attention to detail, and finally how to teach myself to evolve and adjust in all aspects of my life.

That is what a sound, balanced education does; it is the nurture to our nature. With the right teaching environment, each person’s imaginative, artistic self can blossom, and when that creative self manifests, new jobs are generated. These jobs become so much more than just a way of making a living; they become a way of expressing and creating, with one’s skills, thoughts and talents, enriching oneself and everyone around us.

This is the true value of investing in the creative economy; we must recognise it so that we can move towards a better, more egalitarian world.

16.13°C Kathmandu

16.13°C Kathmandu