Culture & Lifestyle

Writers should keep challenging themselves

Samrat Upadhyay reflects on his writing journey and discusses how his work has evolved from strict realism to the imaginative dystopia of ‘Darkmotherland’.

Sanskriti Pokharel

Samrat Upadhyay is a Nepali-born fiction writer based in the United States. His debut short story collection, ‘Arresting God in Kathmandu’ (2001), was the winner of the 2001 Whiting Writers’ Award. His first novel, ‘The Guru of Love’ (2004), was a New York Times Notable Book. Books like ‘Buddha’s Orphans’ (2010), ‘The City Son’ (2014), and ‘The Mad Country’ (2017) are his critically acclaimed books.

His latest novel, ‘Darkmotherland’, is a dystopian novel that explores themes of political corruption, authoritarianism, personal ambition, identity, and the collision of Eastern and Western cultures in a globalised world. He is also a Professor of Humanities at Indiana University, where he teaches creative writing.

In this conversation with the Post’s Sanskriti Pokharel, Upadhyay discusses how his writing has evolved since ‘Arresting God in Kathmandu’ and why he shifted from strict realism to dystopian writing.

You’re known as one of the first Nepali-born writers in English. How has your relationship with that label changed over time?

When my first book came out in 2001, it received some attention in the US, and there was excitement among readers in Nepal as well. When I returned and met readers here, the response was mixed. Alongside support, there was scepticism about how anyone could write about Nepal in English, a language not dominant here. Some also felt that writing in English meant writing mainly for a Western audience, and that raised questions about representation. There was an unspoken expectation that I should somehow represent all of Nepal, which is, of course, impossible.

At the same time, many Nepalis were genuinely proud, and that meant a lot to me. Over the years, my relationship with that label has changed as my work has evolved. I began with a fairly strict realism, but my latest novel, ‘Darkmotherland’, moves beyond that, allowing space for elements I once thought I would never write. If you had asked me ten years ago, I probably would have laughed and said, ‘That’s not my kind of writing’.

What made you think there was a need for a Dystopian novel like ‘Darkmotherland’?

There were a few reasons behind it. One was the way the world was changing. The rise of authoritarian regimes, especially Donald Trump’s presidency in the US, and the growing strength of right-wing politics across Europe and elsewhere, made the present moment feel unsettling.

The other reason was my own evolution as a writer. I wanted to do something new. Writers should keep challenging themselves. We do not remain the same, and neither do our concerns. Each book has its own needs, and I try to listen to what a particular work demands.

Before writing fiction, you studied commerce and explored theatre and journalism. How did those early detours shape the writer you eventually became?

I think a part of me still secretly wants to be an actor. I was deeply interested in performance and was a big fan of Bollywood films.

At the same time, I was naturally drawn to writing, and I was better at it. I began writing short stories during my master’s degree in Hawaii, but I did not imagine they would become a book. In the US publishing world, debut writers are rarely published as short story writers.

Things changed unexpectedly when one of my stories was selected for a Western American anthology. A publisher then asked if I had more stories. I quickly put together the rest of what I had and sent them in, fully expecting another rejection. Instead, they decided to publish the collection. It felt sudden and surprising, but it brought together all those early detours in theatre, journalism, and writing in a way that finally made sense.

When you look back at ‘Arresting God in Kathmandu’ and compare it with your recent ‘Darkmotherland’, what feels most different?

‘Arresting God in Kathmandu’ has its own beauty, but I wrote it with far less caution. I was younger then, and the writing came more easily. At that stage, I believed that once I published my first book, the hard part would be over, that I would have mastered the craft and everything after would feel effortless.

The reality has been the opposite. Writing has become more difficult with time, not easier. That is partly because I have grown and matured as a writer, and I am no longer satisfied with what I produce. I go through many internal drafts now, questioning every choice.

With ‘Darkmotherland’, this was especially true. The emotional weight and the framing of the novel demanded far more care, making it one of the most challenging works I have written.

Your book titles: ‘Arresting God in Kathmandu’, ‘The Guru of Love’, ‘Buddha’s Orphans’, ‘Darkmotherland’ are striking and provocative. How do you arrive at a title?

Titles are something I talk about a lot in my workshops and university classes. For me, the first job of a title is to excite the reader. ‘Arresting God in Kathmandu’ is a good example. There is no story in the collection with that exact title, and people often questioned that choice. But there is a story of Indra descending to earth, stealing flowers, and being arrested. That image felt powerful enough to represent the spirit of the entire book.

With ‘Darkmotherland’, the title refers directly to the dystopian country in the novel. The darkness comes from the political reality of the place, a land ruled by a dictator. Some readers read multiple meanings into the title, but for me it simply names the book’s world.

I am rarely satisfied with a title. I go back and forth between options many times, sometimes changing my mind daily. The process often continues into the editorial stage, where conversations with editors can also shape the final decision.

In ‘Darkmotherland’, Dictator PM Papa is an interesting character. Did real-life figures inspire him, or is he entirely of your imagination?

Dictator PM Papa was inspired, in part, by real-world politics and imagination. I drew on my experiences observing the rise of Trump in the US and the growth of nationalist movements globally, but I also wanted to explore the broader psychology of dictators. I did some research on historical figures like Benito Mussolini, who, like many dictators, was fascinated by physical violence and spectacle.

What tip would you give to aspiring Nepali writers who want to be known internationally?

Becoming known internationally is not something you can plan. It’s unpredictable, and success is never guaranteed. My advice to aspiring writers is to focus on the joy of writing itself. The happiest moments for me are always the first drafts, when I’m discovering the story. Revising second or third drafts is harder because then you are shaping, tightening, and trimming.

Publication and recognition are unpredictable; talented writers may struggle to be published, while less skilled writers may find acclaim.

The key is to focus on your craft and improving your work, not on trying to control how it will be received. Write because you want to tell the story well. Let the rest fall where it may.

You’ve taught creative writing for many years. How has teaching influenced your writing, and has being a working writer shaped how you teach?

Teaching has deeply influenced my writing, and my life as a working writer shapes how I teach. Writing is not something I do on the side. It is central to my life, and that creates a natural connection between the classroom and my own work.

I learn a great deal from my students. They are producing exciting and thoughtful work, and during workshops, I often find myself admiring a particular passage or technique and thinking about how I might use a similar strategy in my own writing. In that way, teaching fuels my creative process. At the same time, when I am struggling with something in my own work, I bring those challenges into the classroom and share them honestly with students.

‘Darkmotherland’ took about a decade to complete. What kept you returning to it, and did the story change significantly over time?

Yes, the story changed a great deal over time. Once I commit to a project, I tend not to let go of it. That persistence is something I also tell my students to value.

My first drafts are about discovery. I write by hand, and the process is deliberately messy. Crossing things out, letting the handwriting loosen, even become unreadable at times, gives me freedom. I am trying to find the story rather than control it too early. Only later do I return with a more critical eye.

With ‘Darkmotherland’, the direction shifted dramatically after the 2015 Gorkha earthquake. Until then, the novel was something quite different. The scale of loss and fear the earthquake produced felt impossible to contain within ordinary realism.

Around the same time, global politics were also shifting. I had not originally planned to write about a dictator, but that figure slowly emerged. When I began the project, Donald Trump was only a Republican nominee, and few believed he would become president. Yet the political atmosphere kept intensifying, and those realities found their way into the novel.

As the book evolved, new characters and storylines followed. The novel kept growing in unexpected ways, and my curiosity about where it might go is what sustained me through those ten years.

Samrat Upadhyay’s five book recommendations

Morning and Evening

Author: John Fosse

Year: 2000

Publisher: Det Norske Samlaget

A Norwegian Nobel Prize-winning author, Fosse explores life, death, and human experience in his distinctive, meditative prose.

Their Eyes Were Watching God

Author: Zora Neale Hurston

Year: 1937

Publisher: J B Lippincott

A classic African American novel that examines identity, race, and gender through the life of Janie Crawford.

Collected Stories

Author: William Trevor

Year: 2009

Publisher: Viking Penguin

This collection showcases Trevor’s skill in creating nuanced characters and compelling narratives across multiple stories.

Fox

Author: Joyce Carol Oates

Year: 2025

Publisher: Hogarth Press

‘Fox’ is Oates’s recent novel, reflecting her long-standing reputation for exploring human psychology and social complexities.

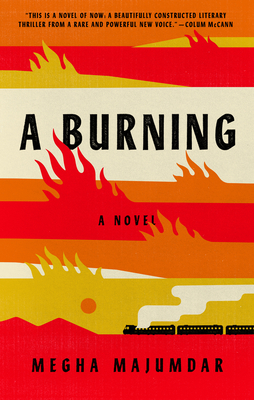

A Burning

Author: Megha Majumdar

Year: 2020

Publisher: Alfred A Knopf

I have taught Majumdar to my students. This one in particular reveals how individuals get caught in dangerous political currents.

16.13°C Kathmandu

16.13°C Kathmandu

.jpg&w=300&height=200)