Culture & Lifestyle

My early years in St Xavier’s School

After being admitted to StX Jawalakhel’s Standard II in January 1972, I spent the winter vacation anticipating the first day of school on February 1.

Pratyoush Onta

By the early 1970s, St Xavier’s School (StX) had a reputation for being the best school in the country for boys. American Jesuits originally founded StX as an English-medium school in 1951. It had expanded to two wings by 1971: a junior school with boarding facilities in Godavari and another wing in Jawalakhel, for day scholars in the junior school and boarders in the high school.

After being admitted to StX Jawalakhel’s Standard II in January 1972, I spent the winter vacation anticipating the first day of school on February 1. However, on the early morning of January 31, King Mahendra (1920-1972) passed away. School remained closed for days as part of the national mourning.

My new friends

When school reopened, except for my second cousin Chatur, I got to meet more than 30 new friends for the first time. They came from families with various surnames: Acharya, Bhandari, Khunjeli, Dev, Gongal, Maharjan (2), Malla (2), Panth, Pradhan, Rana, Ranjan, Regmi, Sharma, Shrestha (several), Thapa, Upadhyay, and Vaidya. The Vaidya friend came from a family related to my mother, whose maiden surname was also Vaidya. One Shrestha friend was so brilliant that he was eventually double-promoted.

Dev’s family was from the Eastern Tarai. The friend with the Thapa surname was a Magar Thapa. One Malla friend was Newa, and the other was a Chhetri. Of course, at the time, I would not have known all these facts. I would also not have noticed the absence of students with the Tamang surname, or many other surnames that reflect different layers of marginalisation in post-18th-century Nepal. I learnt that surnames were important signifiers in Nepali society only much later in my life.

In 1973, several new friends with surnames such as Basnet, Lohani, Maskey and Rajbhandary joined our class. Hence, our class in 1972-1973 contained a fair number of boys from Bahun, Chhetri and Newa families. There was one Madhesi and no Dalits. Janajatis other than Newa kids were mostly missing. As I would learn years later, in the corresponding Standard II in StX Godavari, apart from quite a few Bahun, Chhetri and Newa kids, there was a Chaudhary, a Budhathoki, a Thapa (Magar), a Gurung, a Tamang, two Lamas, and two Sherchans. I don’t know what explains this difference. Perhaps Janajatis other than Newa people were not residentially present in the Kathmandu Valley in significant numbers to send their boys to the day school. Hence, boys from such Janajati families based outside the Valley could only enrol their sons in the boarding wing of StX. While not as diverse as the Godavari class, my Jawalakhel class included people from more social backgrounds than I had been exposed to in my Thamel upbringing.

Kathmandu then

My new friends and I lived in different parts of Kathmandu and Patan. In the early 1970s, the entire Kathmandu Valley was not densely populated. People mostly lived in the core areas of one of the three main cities—Kathmandu, Patan and Bhaktapur—and the rest of the land was primarily agricultural. That is not to say that people did not live in the peripheries of these major towns; they did, both in smaller cities like Kirtipur or Tokha, or in thinly populated villages—kanth—near the edges of the hills surrounding the Valley. My family lived in Thamel. Although the Kathmandu Guesthouse had come into operation in 1968, Thamel was not yet a tourist ghetto. Parts of this residential neighbourhood, the older parallel streets on either side of Bhagwan Bahal, were densely populated by Pradhans and other Newa people, and also many Rana, Basynat, and Pyakurel families.

Among my new friends who lived near the school, those who walked there came from areas such as Kupondole, Bakhundole, Sanepa, Jhamsikhel, Jawalakhel, Lagankhel, and Mangal Bazaar. Although I live in one of these neighbourhoods now, they were mostly foreign to me then. I and many of my classmates who lived in various other parts of the Valley, used to take the school bus. My bus stop was in front of Kaiser Mahal, the gateway to Thamel. On the way back from school, my bus route meandered slowly through Kupondole, Singha Durbar, Putalisadak, Dillibazaar, Bhatbhateni, Nagpokhari, Kaiser Mahal, and Lainchaur.

On the way to school, the route varied a bit, but both routes covered the core of Kathmandu as it existed then. During the monsoons, watching the swollen Bagmati River from the school bus as it crossed the bridge near Kupondole was my favourite activity.

There was very little traffic and all major roads ran both ways, unlike how it is now in Kathmandu’s core. There was no school bus service to the small towns in Kathmandu’s outskirts. In fact, if you lived in Balaju, Baneshwar, or areas north of Panipokhari, you either had to walk to the nearest school bus stop or take public transportation to school.

.jpg)

Our mothers and fathers

Many of our parents were the first in their families to go to college. However, most of our mothers were full-time homemakers. My mother, Mainya Baba Onta (1941–2025), went to college but dropped out to manage our house single-handedly, thus making possible my father’s public life and her children’s education. I don’t know how many of the other mothers held professional jobs. One friend’s mother certainly did. From 1973, she held an administrative position in the Law Campus of Tribhuvan University before switching to teach economics at its Patan Campus in 1977.

Our fathers worked in various professions. Some fathers, including my own, were academics who taught in different colleges. But my father Tirtha Raj Onta left his teaching job in about 1973 and took up an administrative position at Nepal Red Cross. My second cousin’s father was a physicist who taught at Tri-Chandra College. Fathers of at least two friends were medical doctors, one was a surgeon at Bir Hospital and another worked for the then Royal Nepal Army. Another father worked as a soil scientist for the Government of Nepal (GoN). I assume several other fathers also worked for various GoN departments.

There was a father who worked in the finance department of the state-owned airlines; another who worked briefly as an auditor briefly taking up farming. Some probably worked in private business. I do know that there were several full-time farmers and probably many others enjoyed it as a past-time. Thus, we mostly came from families which could be described as middle-class in terms of professional orientation, although on a country-wide scale, we were members of the cultural elite.

School routine

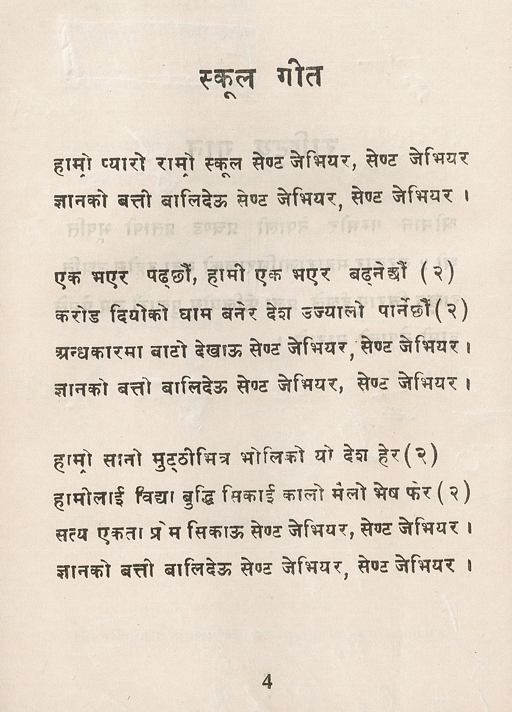

In 1972-1973, our mornings began with a school assembly where we would sing the then national anthem (‘Shreeman, Ghambir, Nepali….’) every day and the school song occasionally (‘Hamro pyaro ramro school, St Xavier’s, St Xavier’s…’). Then our time was broken into a structured routine: two classes and first break; two classes and then lunch; two classes and a games period.

This routine was different from the one I had maintained during 1971 when I was home-schooled by my parents because I was too sick to attend a regular school. Looking back, this was a vital lesson for me: the tedious routine of school life was precisely what fostered a lifelong habit of study.

During the lunch break, unlike at many other schools in the Kathmandu Valley and other parts of the country, most students were not allowed to go outside the school compound.

An exception was made only for those friends who lived near the school: they were allowed to go home for lunch. Hence, lunch was not an adventure for stealing other people’s fruits in nearby gardens, as it would have been the case for our contemporaries in many schools located in rural Nepal then. Most of us who did not live near the school brought food from our homes for lunch. Perhaps one or two ate lunch in the school cafeteria for which there was an extra charge (Rs40 in 1974). Most of the time, my mother packed sliced bread with jam in my tiffin box. I have vague memories of sharing lunch with some of the new friends on occasions.

During the recreational and lunch breaks, we would play on swings and slides. Later, in the higher classes, table tennis and one-wall handball were also popular. Extracurricular physical activities at StX at the time were mainly sports. The Jesuits probably had a philosophy of how sports fit into the making of the character of the young Nepali men they were training at the school. If so, I was not aware of it. As a kid, I had been mighty impressed by the big playing fields in the back of the StX compound, an erstwhile Rana Durbar. Next to Tundikhel in Kathmandu’s centre, I had not seen such big playing fields until then.

I was a sickly boy whose sports-playing ambitions were far ahead of what my body could endure. In classes II and III, by the mid-afternoon, I would often have a headache. The source of those headaches remains a mystery. Perhaps my body, then and even now, has a metabolic system that cannot deal with too many physical activities in the first half of the day. Whatever the case, in my early years at StX, I would use my headaches as an excuse to avoid team sports such as football, softball or kickball. We might have also played throwball, a version of volleyball for small kids.

On the days I did participate, I enjoyed playing football in one of the two “small” fields on the southern side of the two “big” fields. Those small fields—which do not exist in the same form today—were very close to the Central Zoo in Jawalakhel. We would occasionally hear the roars of the big cats while we played. While our peers in Godavari enjoyed wrestling and swimming, we in Jawalakhel did neither. Lacking a pool of our own, we often felt jealous when hearing about their swimming and diving competitions.

All the students were grouped in various teams (Green House, Yellow House, etc). Once a year, we held a sports day where students competed against classmates from other teams. Apart from the regular track-and-field events, tug-of-war, spoon-in-the-mouth race, sack race, and balloon phukne competition were quite popular.

Looking back, as young boys from families with residential roots in the Kathmandu Valley attending the country’s best English-medium school, we enjoyed immense privilege. In classes II and III, we were shaped by the “civilising” education for which Jesuits are world-renowned. Kids from different social backgrounds were amalgamated by that force into a group that gradually absorbed the StX School culture. Amid the tedium of everyday classes, we kids formed bonds of friendship that have now endured for over 50 years.

In 1974, ‘Naya Shiksha’ experimentation reached us as we started grade four. The Jesuit mission had to now accommodate the state’s serious attempt to cultivate Nepali-ness on us kids. But that is a story for another occasion.

16.13°C Kathmandu

16.13°C Kathmandu

.jpg&w=300&height=200)