Movies

Queer, rural, and all too human stories on screen

Showcased at the Queer Film Festival Kathmandu, these short films explore resilience and give voice to stories often ignored in mainstream cinema.

Sanskriti Pokharel

If I Were a Voice

In today’s climate, where queer silencing and institutional abuse remain disturbingly common, ‘If I Were a Voice’ feels necessary. It speaks for the gender minorities whose voices are dismissed. More importantly, it reminds us that sometimes survival begins when one voice dares to rise, and others follow.

In this short-film, a queer student is blamed after a teacher secretly records and leaks an intimate moment, revealing the school’s deep injustice and abuse of power. When the institution chooses silence over truth, students come together through performance to speak out and reclaim their voices.

Denbert Tiamson’s direction is most compelling when it leans into performance. The speech choir becomes more than an aesthetic choice. It functions as a form of resistance, turning synchronised voices into a protest against institutions that prefer silence to accountability. The film understands how systems protect abusers through everyday indifference, procedural calm and selective blindness. This feels relevant, especially in a time when educational spaces continue to fail queer students under the guise of discipline and decorum.

What makes the film resonate is its refusal to isolate queerness as an individual burden. Ralph’s struggle is never framed as a lone fight for dignity. Instead, the film insists on collectivity. Friendship, shared risk and mutual recognition become the only viable responses to power that is entrenched and predatory. This warmth, the sense of classmates standing shoulder to shoulder, softens the film.

There are moments when the symbolism feels overt, and the confrontations occasionally lean towards theatrical excess. Yet even these choices feel intentional, rooted in the director’s background in performance and oral tradition.

Director: Denbert Tiamson

Cast: Lorenze Moral, Chi Carreon, Mark Russel Royo

Language: Filipino

Year: 2024

Duration: 20 minutes

_________________

Mantutiya

The politics of naming sits at the heart of the film ‘Mantutiya’.

Born into a family that was waiting for a son, Mantutiya is given a name shaped by disappointment rather than love. Growing up in a poor village in Dhanusha, she learns early that her gender decides her worth, freedom and the limits of her dreams. ‘Mantutiya’ follows the girl’s journey of breaking away from what was imposed on her.

A name born out of rejection becomes a lifelong burden, shaping how a girl is seen and how she learns to see herself. In Nepal, where patriarchal values still decide whose lives are worth investing in, this feels painfully relevant.

The film moves gently but leaves a lasting weight. It resists spectacle and instead trusts stillness, labour and the slow realities of survival. Oppression here settles into everyday life through names, expectations and silence.

What feels most striking is how the film treats work and dignity. Mantutiya’s life in Janakpur is not romanticised, yet it is never reduced to suffering alone. Her labour as a hotel housekeeper is shown with respect, as something earned and claimed. In a cinematic landscape where women from marginalised communities are often portrayed as victims, this choice matters.

Stories from Janakpur and the Madhesh region rarely find space in mainstream cinema, and when they do, they are often simplified. ‘Mantutiya’ refuses that. The city exists as lived space, familiar and textured, never exoticised.

The closing moment at the Janaki Temple is powerful. Mantutiya moving her body freely within a sacred traditional space feels quietly radical. It is not rebellion for performance, but release. The film reminds us that freedom does not always roar. Sometimes, it begins with the courage to loosen the name that was forced upon you.

Director: Bisestha Bohora and Shreeti KC

Cast: Mantutiya

Language: Nepali

Year: 2025

Duration: 6 minutes

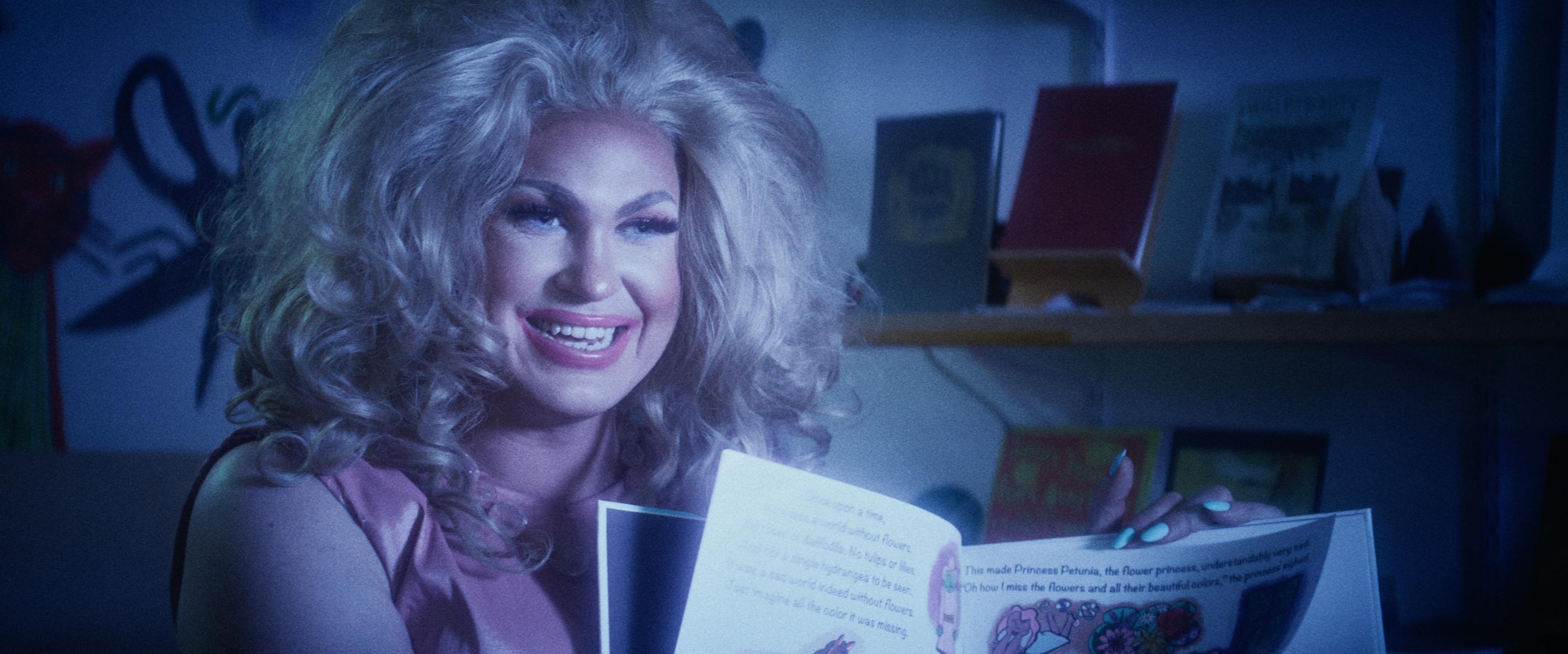

The Last Story on Earth

A drag queen reads fairy tales to children at a local library while protesters gather outside, angry and loud. When an alien invasion suddenly traps everyone inside, her storytelling becomes the only thing standing between humanity and extinction. ‘The Last Story on Earth’ turns a familiar culture war into a sharp, unsettling fable.

Aaron Immediato’s short film blends science fiction with political urgency in a way that feels playful on the surface and deeply alarming underneath. The hostility towards drag performers is not just about morality or fear. It is about control, and about who gets to shape imagination.

The film’s strength lies in how seriously it takes storytelling. The drag queen is not framed as a novelty or provocation. She is a caretaker of wonder. Her voice, gestures and warmth stand in contrast to the rigid anger of the protesters and the cold calculation of the alien force. Immediato suggests that imagination is not harmless entertainment but a form of power. It can nurture empathy, curiosity and resistance.

The film asks why those who claim to defend children are often the first to strip away spaces where children can imagine freely and without fear. In this sense, the story speaks far beyond the American context it draws from.

The library’s confined setting works beautifully. It becomes a battleground where hate, fear and hope collide. The drag queen’s calm persistence feels radical. She refuses to stop telling stories, even when the world seems to be ending.

‘The Last Story on Earth’ feels urgent because attacks on queer visibility continue to grow, often disguised as concern or tradition. The film reminds us that when imagination is silenced, humanity loses more than art. It loses its future.

Director: Aaron Immediato

Cast: Pickle, Dan Kauss, Jamie Lopez

Language: English

Year: 2024

Duration: 18 minutes

A Farewell to Arm

A young man loses a hand in an accident but refuses to let the loss define his future. Leaving behind the friendships and rhythm of city life in Kathmandu, he returns to his village to build and do something. ‘A Farewell to Arm’ follows this turning point with care.

What sets the film apart is its refusal to frame disability solely as tragedy. Sher Bahadur is not treated as a symbol of suffering or inspiration. He is allowed to be ordinary, conflicted and tender. The camera lingers on his routine moments, on work that demands patience, and on the silences that come with starting over. In doing so, the film resists the urge to dramatise pain and instead focuses on endurance.

The emotional core of the film lies in loss that is not always visible. The missing hand is only one part of it. There is also the loss of youth spent in the city, of dreams he dared to dream, and of a life that once felt possible. The film handles this nostalgia gently. Kathmandu appears not as a dream that failed, but as a chapter that had to end. This choice feels honest, especially in a country where migration to cities is often framed as the only path forward.

The decision to return to the village carries political weight. At a time when rural life is frequently depicted as stagnant or lacking ambition, the film subtly challenges that notion.

‘A Farewell to Arm’ matters because stories like Sher Bahadur’s are rarely centred. Disability, rural aspiration and young men choosing to stay rather than leave are still treated as side notes in Nepali cinema. This film brings them to the front, which is praiseworthy. In its warmth and restraint, it reminds us that resilience does not always look heroic. Sometimes, it looks like choosing to stay and learning how to begin again.

Director: Mishlin Gurung and Sabina Shrestha

Cast: Sher Bahadur

Language: Nepali

Year: 2025

Duration: 10 minutes

16.41°C Kathmandu

16.41°C Kathmandu