Movies

When control is mistaken for care

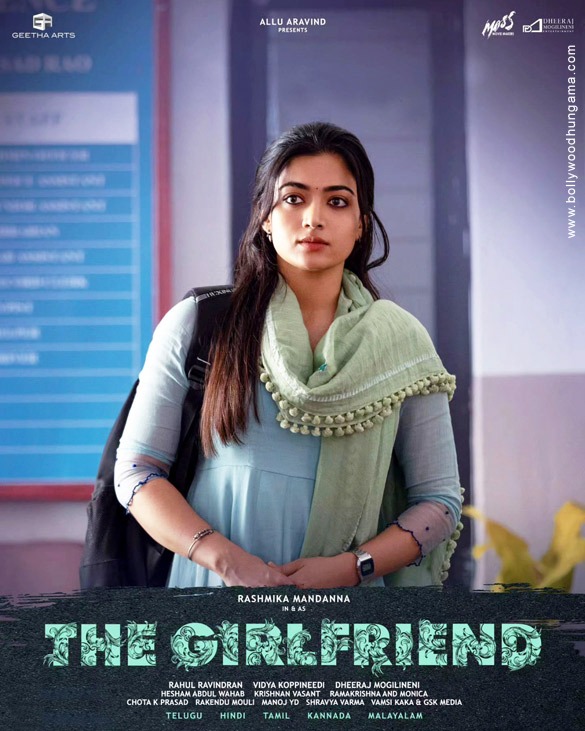

‘The Girlfriend’ exposes how romantic relationships can mask control and entitlement as love, showing the gradual erosion of a woman’s autonomy.

Sanskriti Pokharel

Films like ‘The Girlfriend’ remain relevant across time because they address patterns that persist within romantic relationships, patterns that are often excused, normalised, or even celebrated.

Directed by Rahul Ravindran, the film exposes how control is repeatedly misread as love and how women are trained to endure this confusion. Rather than centring male redemption or romantic resolution, the narrative remains anchored in Bhooma’s (Rashmika Mandanna) gradual loss and partial recovery of agency.

Bhooma’s character reflects a woman socialised to seek safety rather than autonomy. Her attachment to literature is significant. Books become a refuge because they offer a private space that her lived world denies her. Bhooma’s reading is not an escape born of leisure, but a survival strategy shaped by emotional neglect and control.

Vikram (Dheekshith Shetty) represents a familiar masculine archetype sustained by patriarchal reward systems. His aggression, entitlement, and performative dominance are validated by male peers who function as an echo chamber. The film does not isolate Vikram as an anomaly. Instead, it situates him within a culture that celebrates male volatility while dismissing female discomfort as overreaction.

Bhooma’s consent is repeatedly overridden in small, cumulative ways. Her privacy is denied, her relationships with friends are monitored, and her emotional space is occupied. The film accurately captures how such control often appears affectionate at first, making resistance difficult to articulate.

Public exposure plays a crucial role in this dynamic. Bhooma’s relationship with Vikram exists under constant observation, yet her voice is absent from its narration. Vikram’s desire to display her and broadcast about their relationship and affectionate moments reflects ownership rather than intimacy. Bhooma becomes a marker of Vikram’s masculinity rather than a subject with independent desires.

The film also foregrounds the intergenerational transmission of patriarchy. Bhooma’s father and Vikram mirror one another in their possessiveness. Bhooma’s compliance is not weakness but conditioning. The film resists blaming her for staying and instead exposes the social training that makes leaving feel impossible.

Vikram’s expectations of womanhood further reveal the misogynistic logic of the relationship. His attraction to Bhooma’s resemblance to his mother collapses romantic desire into maternal obligation. Feminist critique identifies this as a demand for unpaid emotional and domestic labour disguised as love. Bhooma’s ambitions, her academic goals, her to-do list shrink as her caretaking role expands. Her intellectual and creative pursuits are sidelined, reflecting how women’s aspirations are often treated as secondary to male comfort.

Moreover, when Bhooma performs on stage, she receives applause, recognition, and visibility from everyone except Vikram. Rather than feeling proud, he feels threatened. Her presence in the public eye unsettles him because it challenges the control and hierarchy he has built. He insists that she stay away from the stage, claiming he dislikes others looking at her. The scene is bound to anger viewers, revealing just how insecure he is.

The portrayal of Vikram’s mother is one of the film’s most powerful feminist critiques. She embodies the endpoint of submission. Her drained presence, lack of eye contact, and confinement to domestic space illustrate the cost of lifelong compliance.

The visit to Vikram’s home intensifies the film’s psychological tension. Bhooma is taken there to meet his mother without her consent. Vikram’s mother is introduced through tight, claustrophobic framing, confined to colourless domestic spaces.

When Bhooma recognises herself in this woman, the film articulates a feminist warning. This is not an individual fate but a structural one, produced by gendered expectations and endurance.

Bhooma sees how easily her present could become that future. Bhooma gradually comes to understand that love without autonomy erases her identity.

When Bhooma attempts to leave, Vikram’s response reflects male entitlement. His immediate turn to slut shaming and public character assassination reflects a familiar pattern. A woman who speaks up for herself is punished. The film’s refusal to redeem Vikram is a deliberate feminist choice. It rejects narratives that prioritise male growth over female safety.

The reference to Virginia Woolf’s ‘A Room of One’s Own’ strengthens this feminist framework. Woolf argued that women require space, privacy, and financial independence to create and exist freely. Bhooma’s tragedy lies in never fully accessing such space. She is always watched, directed, or needed. Her struggle is not just emotional but structural.

The movie utilises symbols and imagery to convey her entrapment further. The symbolic imagery of Bhooma lying flat on the forest floor, her arms spread out, as thick, tangled tree roots coil tightly around her body, is chilling. The roots bind her chest, arms, and torso. Her face is turned upward toward the sky, eyes wide and filled with fear and helplessness. She appears conscious but trapped, unable to move, as if caught between resistance and surrender.

Symbolically, the scene suggests emotional and social entrapment: the roots resemble forces like past trauma and toxic relationships, holding her down.

Ultimately, ‘The Girlfriend’ functions as a feminist critique rather than a romance. The film portrays a reality many women live. It presents a pattern that continues across relationships and generations. The film provides awareness rather than entertainment and urges viewers to recognise control, question silence, and reconsider what is often mistaken for love.

Those who dismiss the film as exaggerated or unrealistic may want to reflect on what unsettles them. Is it the narrative, or the mirror it holds up?

The Girlfriend

Director: Rahul Ravindran

Cast: Rashmika Mandanna, Dheekshith Shetty, Rao Ramesh

Duration: Telugu

Year: 2025

Language: 2 hours 18 minutes

Available on Netflix

16.13°C Kathmandu

16.13°C Kathmandu