Editorial

The poverty paradox

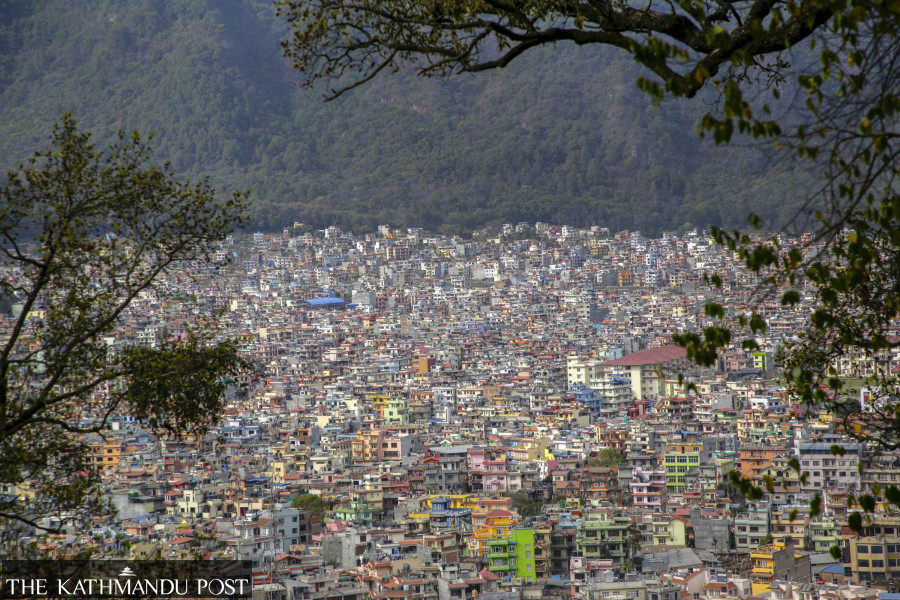

The steady rise in urban poverty calls for a shift in the country’s rural areas-centric approach.

With 66 percent of Nepal’s population living in municipalities, its urban population has steadily increased over the years, and so has urban poverty. According to the recently published fourth Living Standard Survey 2022-23 of the National Statistics Office, urban poverty climbed up to 18.34 percent in 2022-23, from 15.46 percent in 2010-11. Meanwhile, rural poverty came down to 24.66 percent, from 27.43 percent in 2010-11. The poverty percentage is the highest in Sudurpaschim Province (34.16 percent) and the lowest in Gandaki Province (11.88 percent).

It is common knowledge that people migrate to cities in search of better opportunities, infrastructure, education and health facilities. Also, when they are dissatisfied with their limited lives in remote places, they seek refuge in cities and urban areas. However, only a handful of people who make the transition can earn a proper living, while many others end up in slums with poor sanitation, inadequate shelter and dirty potable water. This is in fact a worldwide problem. The United Nations Statistics Division shows that between 2014 and 2018, the population living in urban slums globally rose from 23 percent to 24 percent. The issue of slum dwellers has been a headache for the office of Kathmandu Metropolitan City, as Mayor Balen Shah has often tried to drive them away without proper settlement plans.

Urban poverty remains Nepal’s invisible underbelly, as policymakers’ focus remains on rural poverty. It also stems from the mindset that people, just by the virtue of their living in cities, are well-off. They, therefore, cannot be poor. This is why our poverty-reduction programmes are also lopsided. One such programme run by the country’s Poverty Alleviation Ministry called “Bisheshwar with the Poor”, unsurprisingly, focuses only on the rural poor. While it is vital to cut down on rural poverty, the importance of programmes aimed at alleviating (rising) urban poverty cannot be overstated.

Moreover, the government often leaves the urban poor in a lurch. For instance, even though Nepal’s Urban Development Strategy 2017 was aimed at developing a vibrant urban environment, infrastructure and jobs, the authorities have fallen far behind in its implementation. The strategy also discusses implementing a Community Development Programme focused on the urban poor, housing, infrastructure and transport, which too are far from being realised.

Unless Nepal learns to deal with the urban poor, the country will continue to be beset by a high level of poverty. As per the survey, 20.27 percent of the country’s population still lives below the poverty line, compared to 25.16 percent in 2011. As Nepal prepares its 16th periodic plan, urban poverty alleviation through job creation and budgetary provisions should be the government’s priority. It should also include plans for federal, provincial and local levels to work together to solve slum-related problems. Indonesia, the fourth most populated country in the world, is not free of slum dwellers either. But it has effectively managed them through its mass intervention called the National Slum Upgrading Project. We shouldn’t delay emulating such interventions.

There is a need to integrate the urban poor in development programmes and policies and keep a record of those in need of immediate help and attention. As important is helping people stay in their villages and to encourage people working in urban areas to take their skills back to their rural bases. Poverty anywhere—rural or urban—is a big threat to a country aiming to achieve middle-income status and Sustainable Development Goals by 2030.

20.9°C Kathmandu

20.9°C Kathmandu