Columns

Regulations, revolution and chaos

The media must review their performance of 2025 to ensure they continue to function as the fourth estate.

Bhanu Bhakta Acharya

In 2025, Nepal experienced perhaps the most turbulent year in press freedom after the decade-long conflict between the government and the Maoist forces. Nepal was already 16 places behind in the world press freedom index in the year, compared to the previous year’s ranking of 74. The worsening scenario in Nepal’s media landscape is likely to push the ranking further down, smearing its most free press status in South Asia.

Social Media Bill

The government introduced the controversial social media bill, called ‘Bill on the Operation, Use, and Regulations of Social Media’, to the National Assembly. The bill obliged all social media companies operating in Nepal to register with the government. Government officials argued that the bill was urgent in controlling harmful online activities, such as cyberbullying, phishing, scams and hacking. However, political stakeholders, media organisations and civil society groups opposed the bill. They argued that it was against the spirit of Article 17 (right to free expression), Article 19 (right to communication) and Article 27 (right to information) of the 2015 Constitution. These articles collectively guarantee freedom of expression and press freedom in the country.

Section 16(2) of the bill states that “one must not post, share, like, repost, live stream, subscribe, comment, tag, use hashtags, or mention others on social media with malicious intent.” The law allows authorities to impose hefty fines, revoke licences and impose prison sentences on offenders, with fines exceeding $10,000 and up to five years of imprisonment for content deemed harmful to national sovereignty, territorial integrity, national unity or security.

The vague definition of the bill covers all forms of journalism practices, such as accessing, moderating and disseminating information using social media platforms, deeming such activities to be considered digital offences. More seriously, the bill empowers government officials to remove content if they believe such content is ‘indecent’, ‘misleading’, or ‘defamatory’ on digital platforms.

Moving further, controversy on the proposed social media bill drew attention from international organisations such as the International Federation of Journalists (IFJ), Reporters Without Borders, Committee to Protect Journalists (CPJ) and many others. These organisations urged the amendment of the bill through in-depth dialogues with stakeholders, suspecting that government authorities could misuse the bill against professional journalists.

Gen Z protests and consequences

The KP Sharma Oli-led government urged social media platforms to register in Nepal under the Directives for Managing the Use of Social Networks, 2023. However, only three platforms (TikTok, Viber and Weetok) registered by the deadline. On August 17, the Supreme Court ruled in favour of the government’s directives, mandating all social media platforms to register in the country. On September 4, the government suspended 26 platforms that ignored the directive.

Gen Z-ers organised a protest in Kathmandu on September 8. The protest turned violent, killing 19 young protesters in a single day. It quickly spread into nationwide unrest, with vandalism and arson of government buildings, the residences of politicians and media houses. According to a report published by the Federation of Nepali Journalists (FNJ), a total of 26 incidents of press freedom violations were recorded due to the protests that affected over 100 journalists and media houses.

Journalist safety worsened

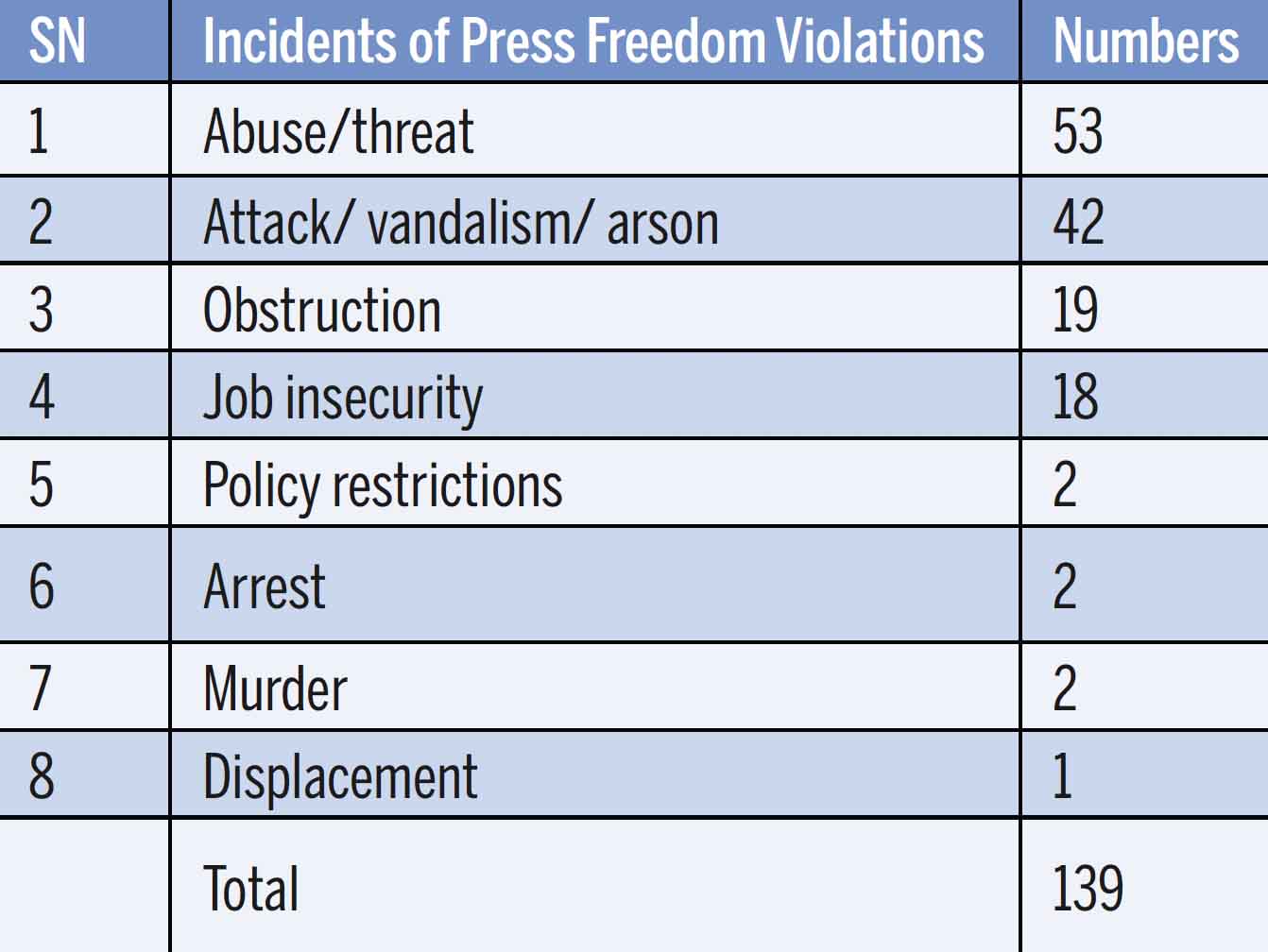

In 2025, FNJ Nepal reported 139 incidents of freedom of the press violations, affecting 218 journalists and 31 media houses. Of them, 53 incidents related to threats to journalists, whereas abuse of journalists was the highest in the decade. Likewise, 42 incidents included physical attacks, vandalism and arson. As the number of press freedom violations increased almost three times more than in 2024, it signals the vulnerability of journalists’ safety in the country.

The safety of journalists was a major concern throughout the year. Demonstrations by pro-monarchist groups, Gen Z and other groups directly impacted journalists and media houses due to their professional performance.

While covering a demonstration in Kathmandu, photojournalist Suresh Rajak of Avenues Television was caught in a building that was set on fire by pro-monarchist protestors and burned alive on March 28. In the same incident, two other journalists were assaulted. Offices and vehicles of national media, including Kantipur Media Group, Annapurna Post and Himalaya Television, were vandalised, set on fire, and journalists were harassed for their professional role.

On June 16, an arrest warrant was issued to journalist Dil Bhushan Pathak from the Patan High Court under the Electronic Transaction Act 2008 after a complaint was filed against him with the Cyber Bureau of Nepal Police. Pathak had published a controversial report on his YouTube channel claiming connections between a former prime minister’s family and the Hilton Hotel in Kathmandu.

Although the government and the political stakeholders keep repeating the fact that the safety of journalists was a major concern, crimes against journalists remained unresolved. Two plausible underlying reasons may have overshadowed the safety issue: First, the government's primary focus on imposing social media regulations during the first half of the year, and second, increased political vulnerability and chaos in the latter half of the year.

Way forward

Social media platforms are critical tools for traditional news outlets for information gathering and dissemination, and a large majority of the public relies on these platforms for news consumption. These platforms are instrumental in facilitating constitutional rights, and, as such, they should be considered an intrinsic part of the freedom of expression and press freedom. Obstructions on these platforms may pose substantial challenges to journalists in their routine of news reporting, production and dissemination.

Several news media institutions and outlets are often targeted in different protests, which raise serious concerns with respect to their professional performance. Two important aspects, which may have triggered this sense of concern, are: (a) mainstream media may have overlooked the grievances of society, leading to a trust gap, and (b) these media outlets mostly cover big newsmakers such as politicians, industrialists and social leaders, failing to address grassroots issues. Further investigation is warranted on why social media platforms, compared to traditional mainstream media, have been more effective in reflecting public grievances against the government.

Finally, Nepal’s social media revolutions and upheavals indicate that mainstream news media and social media may serve the interests of two distinct groups: the powerholders and the grassroots. When media outlets overly engage in prioritising the interests of powerholders, the media’s function as the voice of the voiceless can be compromised, and the isolated public may ventilate their frustrations via social media platforms. News media organisations should review their performance to ensure that they are functioning as the fourth estate to make the powerholders accountable to the public.

16.13°C Kathmandu

16.13°C Kathmandu