Culture & Lifestyle

‘Women cannot trek’: The myth three sisters set out to break

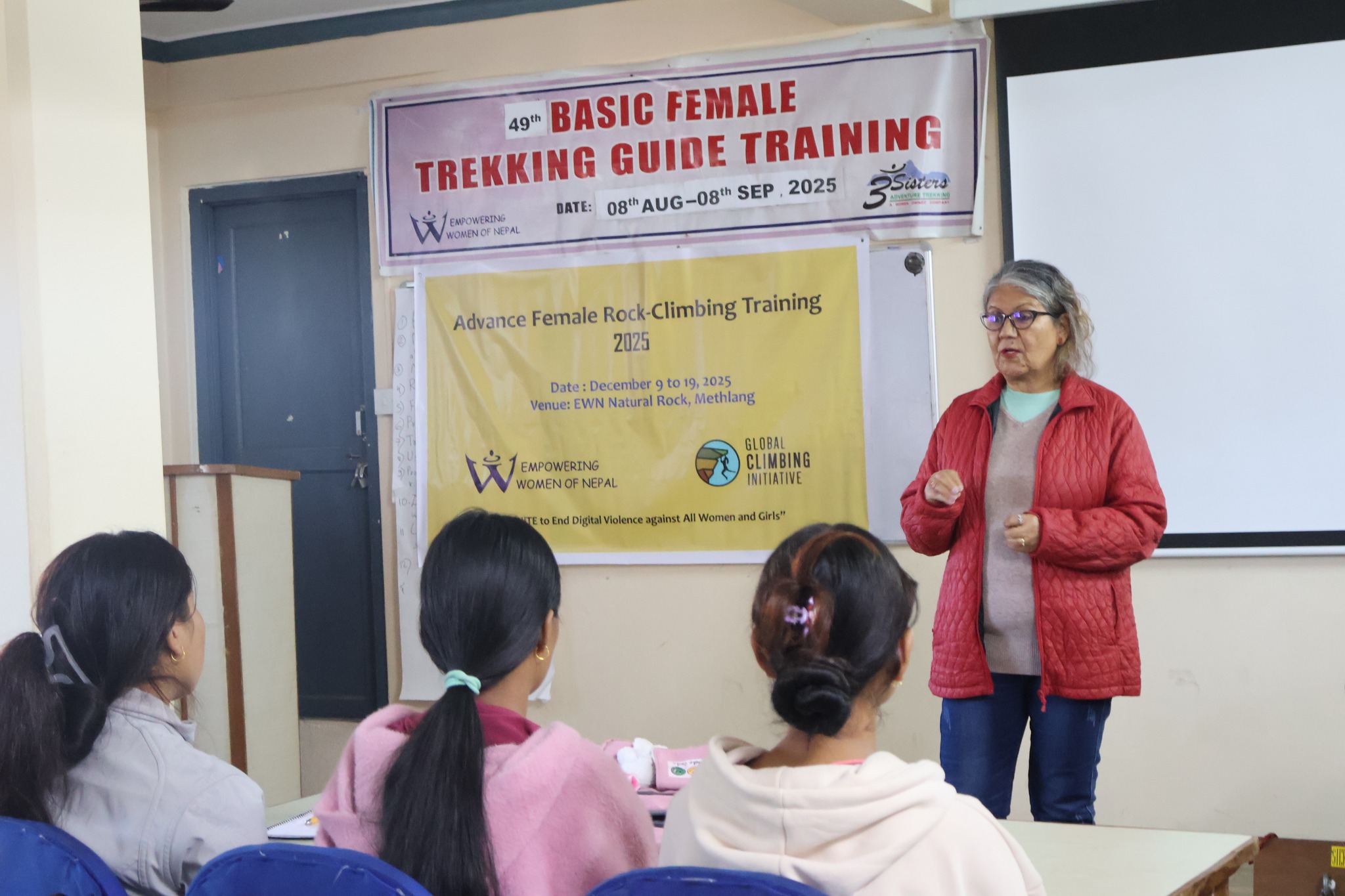

For over 25 years, the Chhetri sisters, who founded Empowering Women of Nepal, have paved the way for female guides, overcoming all obstacles and prejudices.

Britta Gfeller

“Women cannot trek. They are too weak. They will turn back after a couple of days on the trail. Going to the mountains is too dangerous for them. They should stay at home,” these were some of the prejudices that Nepal’s first female trekking guides faced.

“It was a totally new concept for women to be guiding. It was difficult in the beginning; we had to explore everything ourselves,” says Lucky Chhetri, one of the three founders of Empowering Women of Nepal, an NGO that has been training female trekking guides for more than 25 years.

Lucky Chhetri and her two younger sisters Dicky and Nicky, grew up in the Darjeeling region to Nepali parents. Never would they have imagined making a career in outdoor sports. “In our childhood, we were not adventurous or outgoing,” remembers Chhetri. “There was no television or mobile phone, so we used to play a lot outside with friends. But we never went walking or climbing.”

For the oldest Chhetri sister, this changed when she enrolled in a mountaineering course in her mid-twenties. “I never had the chance to do anything as tough or adventurous. But in that moment, I discovered my love for the mountains and the snow,” she says. “I was so happy and full of energy. I was a lot more confident in the mountains.”

Still, she had no plan to become a guide. Instead, she moved to Kathmandu for her master’s degree at Tribhuvan University, and in the course, she helped with research projects that brought her to remote areas of the country. “I was amazed to see the beauty of Nepal. At the same time, the situation of the local people was very tough—mostly for women,” she remembers. “Most men left the villages to find a job and earn money. But the women stayed behind. They had to do everything but received nothing in return, often not even a decent meal for themselves and their families. It was terrible.”

Chhetri wondered what to do, but had no answer at that point. It was only years later, when she finally had an idea. After their father passed away in 1992, the Chhetri family wanted to move to a new place. Lucky convinced her sisters, mother and other family members to move to Nepal. They settled in Pokhara—and loved it immediately.

They ended up opening a guest house and a restaurant, where they welcomed tourists from across the world. “Can you imagine a women-run business 30 years ago?” Chhetri asks. “The tourists loved it!” And many felt comfortable sharing the unpleasant experiences they had had while trekking with a male guide. “There was no other option than trekking with a male guide back then,” Chhetri says. “But when the trekkers came back, some were telling us that they had had a bad time; it was rough with some male guides, they were pushing too hard. Some of them were drunk or threatened the female trekkers.” That was the moment when the sisters came up with the idea of leading treks and training other women to become trekking guides.

“I started thinking of the women of the remote mountain areas again. If they could do this job, their lives would change. How wonderful this would be!” People were not very supportive in the beginning, she remembers. But the three sisters persevered.

The first training they organised was with an existing training centre, which normally only offered courses for men. The Chhetri sisters found seven other women to join a female-only training. It included English language, topics of tourism, trekking, plants, animals, culture, religion, environment and how to interact with guests. “The training was great, and we appreciated the trainers,” Chhetri recalls. But for some other participants, the training was too hard, especially for those from disadvantaged backgrounds who were not used to this kind of education. The training scared them; they felt like they were not capable of being guides.

But the sisters did not give up. Together with the experts and trainers, they worked on the curriculum, redesigned the course, and practised. After two years of work, they were satisfied with the result and offered their own training tailored to women in 1996. Since 1999, they have been running the course regularly. “It’s a welcoming atmosphere. The women really enjoy it and appreciate the progress they see,” Chhetri says.

The same year, they registered their non-profit organisation, Empowering Women of Nepal, through which they offer free training. “It’s not simply guide training,” Chhetri explains. “It’s also women’s empowerment, a course in leadership and women’s rights.”

The courses also include on-the-job training. So far, over 2,500 women have completed the training; many of them are now employed by trekking organisations—the one from the Chhetri sisters or others—, have started their own companies, or work as freelance guides.

Lucky explains why there are still fewer female guides than male guides in the field: “Some women drop out because they have children, and there are a lot of responsibilities for mothers. Or because their shape or strength changes after pregnancy. But compared to when we started, there are so many female guides now.”

Nepali women not only become guides through the training and earn money, Chhetri explains. “They also grow personally and build self-confidence. They learn they can become anything and they can go anywhere.”

16.69°C Kathmandu

16.69°C Kathmandu

.jpg&w=300&height=200)