Culture & Lifestyle

Building Nepal’s queer disability movement

Despite growing awareness of LGBTQIA+ rights in Nepal, queer people with disabilities remain among the most overlooked groups. One organisation—Rainbow Disability Nepal—is working to change that..jpg&w=900&height=601)

Britta Gfeller

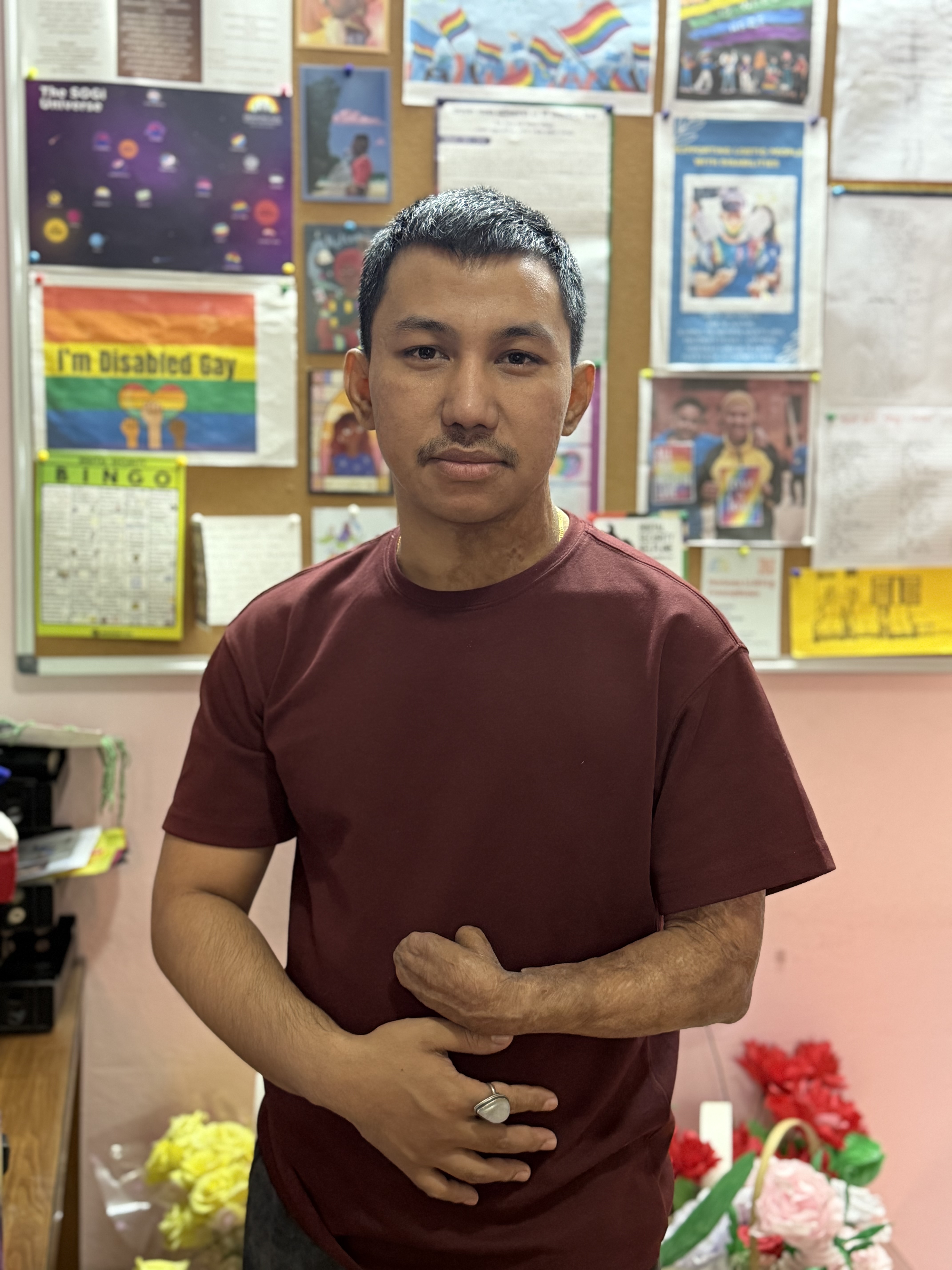

Queer and disabled—two parts of an identity that intersect and make everyday life difficult for many people affected. One of them is Aaditya Rai, founder and managing director of Rainbow Disability Nepal (RDN), an NGO that supports vulnerable individuals with disabilities in the LGBTQIA+ community across Nepal.

“Being queer and disabled is challenging in every aspect of life,” the 32-year-old says. When he first spoke up in the media about being queer and physically disabled in 2013, he was kicked out of the orphanage he was living in at the time and lost his education scholarship. He spent several years living on the street and had to fend for himself without any help. “Nobody wanted to give me a job. In this situation, there were only two options for me: begging and sex work.”

Rai endured this difficult period and later enrolled in college. During his bachelor’s degree in social work, he decided to start a network for LGBTQIA+ people with disabilities. “I had never met another openly queer person with a disability,” he remembers. “I was connected with the LGBTQIA+ community, but I was always a bit different from the others. I have both identities; it was challenging to find myself in that community of non-disabled people. And it was also hard for them to accept me.”

He remembers being curious and having many questions. “I was wondering why I could never find someone like me.” When he first started RDN, he used social media platforms like Facebook, Instagram, and the gay dating app Grindr to reach out to queer people with disabilities, share his story, vision, and mission for his new organisation, and start bringing the community together.

In 2022, Rai officially registered RDN—a tiresome process he invested all his personal savings in. He hired several staff members, many of them queer people with disabilities. Among others, the organisation now employs two outreach workers, one in Pokhara and one in Chitwan. They visit different areas to share their knowledge, spread information about RDN, and find queer people with disabilities who might need support.

RDN is the first organisation in Nepal, and one of the first worldwide, Rai says, to fight for the rights of queer people with disabilities. “I started it because my community needs a voice and visibility. I fought for myself; I was able to study. Now I can support others,” Rai says. “My story and my experience are my biggest strengths. If I don’t start, then who will? And if I don’t come out and speak, who will?”

He faced many obstacles. He says that neither the LGBTQIA+ community nor the disabled community were supportive of his work. “Many have a narrow definition of the human rights they fight for,” Rai says. He has so far also not received any funding from Nepal-based organisations or the government, but relies on donations from international donors.

RDN’s work is broad. The first step for new members is often peer-to-peer counselling. “At first, it is very awkward for many. They don’t have the terminology to define their gender, sexuality or disability,” Rai explains. “But it’s important to know yourself. Only then are you able to claim your rights.” Many queer people with disabilities start to get more comfortable once they learn that they are not alone in what they are feeling and experiencing. “I tell them that we are people with different physicalities and who identify differently. Our stories might be different, but the challenges we go through are almost the same.”

Many queer people with disabilities have no other network which supports them—many have been outcast or abandoned by their families, they are in dire financial situations and for many, it is almost impossible to find a job due to their disabilities and the prejudices they face, Rai says.

Therefore, RDN often provides direct support—such as paying rent, college fees, study material, food and warm clothes. For others, the organisation offers life-skills training in barista, tailoring, or the beauty sector. The goal is to provide community members with the skills and education to find jobs and earn their own money.

Amuka BN, a trans man with physical disabilities, has received support from RDN. The organisation not only assisted him during his bachelor’s degree in social work, but also in his personal development. “I learned to express myself, and it helped me grow as a person,” he says. Khagendra Rana, a queer man with a physical disability, adds: “I can’t imagine a life without the organisation. They treat me like family, while I get no support from my own family.”

In addition to direct support, RDN organises public awareness programmes and social media campaigns to inform people about the situation of queer people with disabilities, their challenges and their rights.

Rai has received several international awards for his commitment. For example, he was one of five people honoured with the Emerging Leader Award by the United Nations Development Programme and the LGBTQ organisation ILGA in 2024. In the same year, he was one of the Hero Award for Social Justice Honourees. This award celebrates individuals who have made significant contributions to advancing the human and civil rights of LGBTQI individuals and those affected by HIV in Asia and the Pacific.

“These awards gave us visibility and recognition,” Rai says. “For a long time, I never met openly queer people with disabilities at international conferences. But now people are seeing us.”

He now gives speeches at international conferences on the rights of queer people with disabilities, and many people from other countries have contacted him for advice on their activism.

What he is still waiting for is appreciation from the Nepali government or Nepali NGOs. “They also have award ceremonies here. But so far, my work and the work of RDN have never been recognised,” Rai says. He is hoping for more allies to support the organisation’s work. “People should open their minds and try to understand other people’s life stories and the challenges other people face.” RDN also welcomes non-disabled or non-queer people to support their work and to donate to continue their activities.

“My path has not been easy. But I found a purpose in my life,” Rai says. “I had the opportunity to work abroad—in the US or UK. But I decided to stay here and work for my community. I couldn’t imagine doing anything else.”

16.13°C Kathmandu

16.13°C Kathmandu

.jpg&w=300&height=200)