National

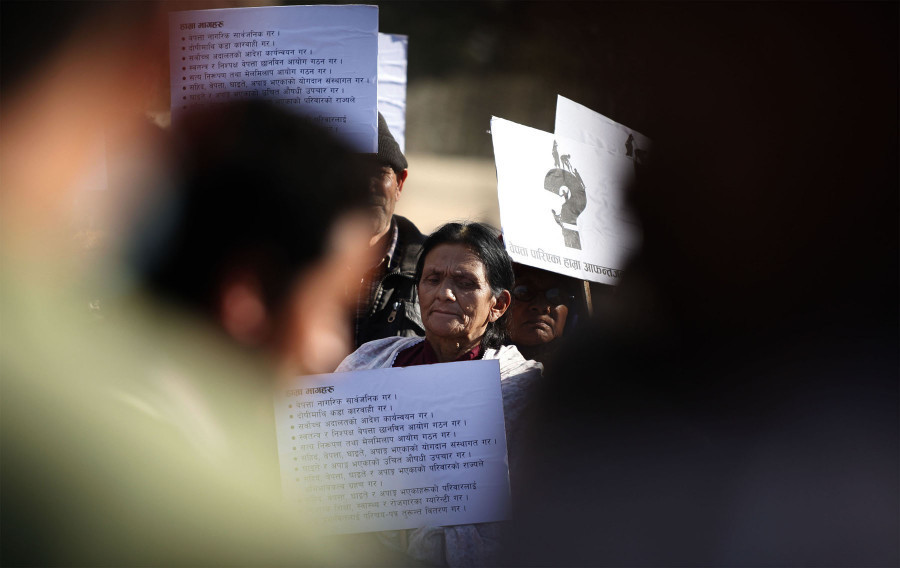

Tenure of two transitional justice bodies to be extended but this is not enough, stakeholders say

Investigation has not been completed even of a single case since 2015. Law that allows amnesty to rights violators must be changed first, victims and activists say.

Binod Ghimire

The government has decided to extend the terms of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission and the Commission of Investigation on Enforced Disappeared Persons and the tenures of the commissioners of the two commissions by around six months.

The tenure of the two commissions formed in 2015 to investigate the conflict-era cases of atrocities is expiring on February 9.

Minister for Law and Justice Lila Nath Shrestha said after the consent of Prime Minister KP Sharma Oli, on Sunday he submitted a proposal to revise the Enforced Disappeared Enquiry, Truth and Reconciliation Act-2014 for the extension till July 15.

“As I was not present at Monday's Cabinet meeting, I formally cannot say if it was endorsed,” he told the Post. “However, I believe it got through because the ordinance was prepared with consent from the prime minister.”

The terms of the two commissions will be extended once President Bidya Devi Bhandari authenticates the ordinance issued by the government.

Shrestha said the government decided to extend the terms till mid-July with a view that it would be better for the new government, that will be formed after the snap poll, to make the long-term decision on issues like transitional justice. The Oli government on December 20 dissolved the House of Representatives and announced midterm polls for April 30 and May 10.

The officials of the commissions said six months is too short for them to make any moves towards the investigation of the complaints. “The six months is an extremely short time for us to do anything,” Ganga Dhar Adhikari, spokesperson at the disappearance commission, told the Post. “No matter, the government continues our team or brings the new one, it should be given ample time to function.”

The disappearance commission has sought four-years to complete its job.

The government, however, remains undecided over the amendment to the Act as per the 2015 decision of the Supreme Court to remove the provisions related to giving blanket amnesty to those involved in gross human rights violations like torture, rape, and murder.

Conflict victims from the decade-long Maoist insurgency between 1996 to 2006, the human rights defenders, and the officials at the commissions have been demanding the amendment as per the apex court’s verdict which directed the government to revise the amnesty provisions in the Transitional Justice Commission.

“The chairs and members appointed on the political sharing cannot provide justice to the conflict victims,” Charan Prasai, a human rights activist, told the Post. “The extension is just an illusion to show to the international community that the government is working to provide justice.”

Ganesh Datta Bhatta, chair of the truth commission was appointed under Nepali Congress quota while Yubraj Subedi was picked as the chair of the disappearance commission on Nepal Communist Party quota.

Prasai said no matter how many times the terms of the commissions are extended, they won’t deliver justice unless the victims’ community is taken into confidence and the Act is amended as per the 2015 Supreme Court ruling.

“I am also in favour of abiding by the Supreme Court’s verdict,” said Shrestha. “However, this is a serious issue which cannot be decided solely by the government without a consensus from the Nepali Congress and the then Maoists.”

The two transitional justice commissions were formed in February 2015 with a two-year mandate to complete investigations into the conflict era cases of human rights violations and recommend reparations. However, the commissions couldn’t even collect the complaints during the period. The government, through a revision in the Act extended their terms by another two years.

In its four years of tenure, the previous truth commission received 63,718 complaints and completed a preliminary investigation that involved the recording of statements from only 3,787 of the complainants.

Similarly, between 2015 and 2019, the disappearance commission received 3,223 complaints from family members saying their loved ones had disappeared during the decade-long conflict. Of these, the commission segregated 2,506 complaints saying the rest didn’t fall under its jurisdiction.

The government in January 2019 revised the Act yet again with the possibility of extension of the commissions by two years. However, following their failure to deliver, the terms of the chairpersons and members of the commissions were extended only till April 15, 2019.

New sets of office bearers in the Truth and Reconciliation Commission and the Commission of Investigation on Enforced Disappeared Persons were appointed in January next last year despite the reservation of the victims, human rights defenders, and national and international human rights organisations. They blamed the chairpersons of commissions and members were appointed without transparency in the appointments.

In the last year the new teams too have not been able to work towards providing justice to the thousands of victims. The disappearance commission has completed a preliminary investigation of all the complaints while the truth commission has done the primary investigation of around 5,000 complaints.

However, they haven’t completed an investigation into a single case.

Victims say the government's move to extend the terms of the commissions portrays the government’s insensitivity towards them.

“Shouldn’t the government evaluate their one year’s performance before giving them an extension,” Maina Karki, chairperson of the Conflict Victims Common Platform, told Post. “We are against the extension.”

Karki said rather than giving extension, the government should bid farewell to the chairs and the members and start a new appointment process after amending the Act as directed by the Supreme Court.

Suman Adhikari, whose father was killed by the Maoists in 2002, said he along with families of other victims of the decade-long conflict had for a long time been trying to meet the Oli and Shrestha to put their concerns as the terms of commissions neared expiry.

However, they had been avoiding different pretenses. “They had been ignoring me because they wanted an unconditional extension of the commissions,” he told the Post. “We have lost our faith both on the government and commissions.”

17.12°C Kathmandu

17.12°C Kathmandu