Valley

Supreme Court set to hear review petition on its landmark 2015 ruling

In February 2015, the Supreme Court issued a landmark ruling ordering the government to revise the Enforced Disappearances Enquiry, Truth and Reconciliation Commission Act-2014. The court ruled that the law failed to adhere to the principles of transitional justice and international practices.

Binod Ghimire

In February 2015, the Supreme Court issued a landmark ruling ordering the government to revise the Enforced Disappearances Enquiry, Truth and Reconciliation Commission Act-2014. The court ruled that the law failed to adhere to the principles of transitional justice and international practices.

The verdict, which came in response to a writ filed by a group of 234 conflict victims, struck down almost a dozen provisions in the Act and directed the government to ensure that no amnesty is awarded in cases of serious human rights violations committed during the decade-long insurgency.

But in April that year, the government led by Sushil Koirala filed a review petition, challenging the ruling issued by a special bench led by then chief justice Kalyan Shrestha. Then chief secretary Leela Mani Paudyal had filed the petition through the Office of the Attorney General Office on the government’s behalf.

The petition, which gathered dust in the court for four years, is up for hearing—on Thursday. And this has caused concern among conflict victims and human rights defenders, as the hearing is set to take place at a time when the government is facing pressure—from conflict victims and rights defenders at home as well as the international community—to amend the Act in line with the 2015 court verdict and international obligations.

“It’s hard to believe that it is just a coincidence,” Kapil Shrestha, a professor at the Tribhuvan University and a former member of the National Human Rights Commission, told the Post. “I won’t be surprised if the verdict gets reversed.”

Human rights activists and conflict victims say they are now worried, as the landmark verdict had given them hope for justice and a reversal could jeopardise the entire transitional justice process that has dragged on for more than a decade now. “I am definitely worried,” said Suman Adhikari, a leader of the conflict victims and one of the 234 petitioners. “Yet, I am hopeful that the court won’t go against its own decision.”

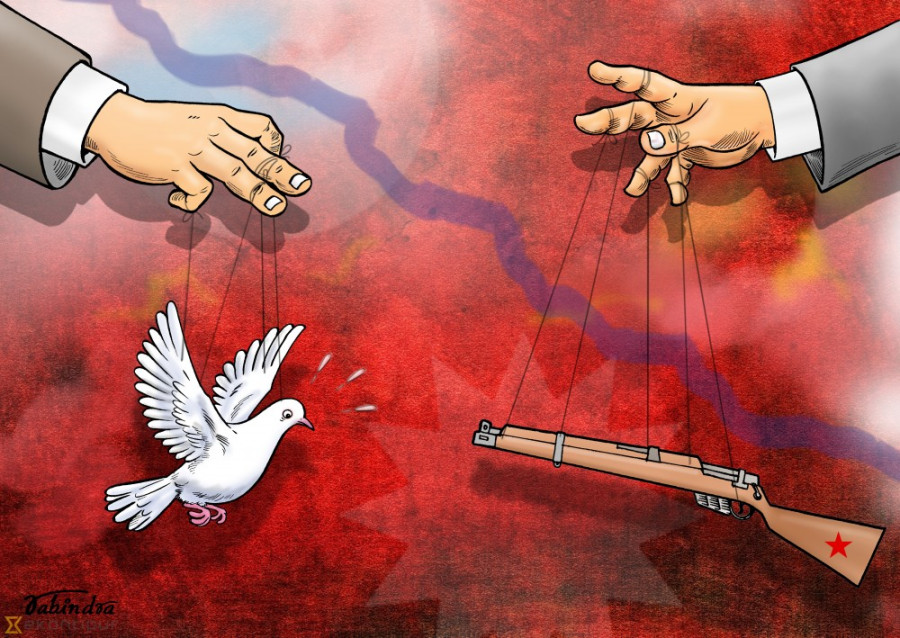

When the court had passed the verdict four years ago, the erstwhile Unified Communist Party of Nepal (Maoist) had taken serious exception to the ruling and claimed that it was against the peace accord.

In the review petition, the government questioned whether the verdict by Shrestha’s bench was as per the spirit of the 2006 Comprehensive Peace Accord and the 2007 Interim Constitution.

The core intention of the review petition is to nullify that verdict and restore the amnesty provision and reconciliation at the discretion of commissions and government, instead of the victims as per the verdict.

Initially, the apex court had said the decision from the full or special bench cannot be reviewed. But then the government refused to budge and filed yet another petition against the Supreme Court’s decision to quash the review petition. The court later allowed the government to register the review petition.

The hearing now also comes at a time when political parties are in talks for having “their” people in the transitional justice mechanism, as a government-instituted recommendation committee is working to sift through the applications—a total of 57—to recommend officials for the Truth and Reconciliation Commission and the Commission of Investigation on Enforced Disappeared Persons.

The international community has already expressed its concern about the procedure to select officials for the commissions and Nepal’s non-committal attitude towards amending the Transitional Justice Act.

In the second week of April, five special rapporteurs under the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights wrote to Foreign Minister Pradeep Gyawali, seeking transparency and proper consultation before selecting the members and chairpersons of the transitional justice commissions. They also drew the government’s attention to the delay in amending the Transitional Justice Act.

The UN letter came on the heels of Gyawali’s commitment in Geneva that there would be no blanket amnesty for the perpetrators of serious human rights violations and that the Nepal government would amend the Act in line with the Supreme Court ruling.

Earlier in January, nine foreign missions based in Kathmandu, at the initiative of the UN, had sought clarity from the Nepal government on its plans to take the transitional justice process forward, ensure broader consultation with the stakeholders and amend the Act.

Without amending the Act, conflict victims have said repeatedly, that the commissions, which have collected more than 63,000 complaints, won’t be able to do much. Though the government has often said it would follow international practices and abide by the Supreme Court ruling, there has been no progress.

Advocate Dinesh Tripathi, who argued on behalf of the 234 petitioners, said a hearing on the review petition at this time looks like a ploy to delay the process.

“A court ruling may be revised if new proofs are found or if it contradicts the precedent,” Tripathi told the Post. “However, since the government is trying to keep the judiciary under its influence, we have to be cautious.”

Conflict victims said there is no option but to trust the country’s judiciary and they believe the court won’t do injustice to them.

Shrestha’s bench, which passed the landmark ruling in 2015, included Cholendra Shumsher Rana, who is the incumbent chief justice.

A conflict victim said a reversal of the verdict would raise a moral question for Rana too.

“The world is watching our transitional justice process,” he said on condition of anonymity, citing the case sub judice in court. “I believe the apex court would not want to lose its credibility by reversing the earlier decision.”

9.7°C Kathmandu

9.7°C Kathmandu