Money

Virus turned Nepalis into bookworms, say traders

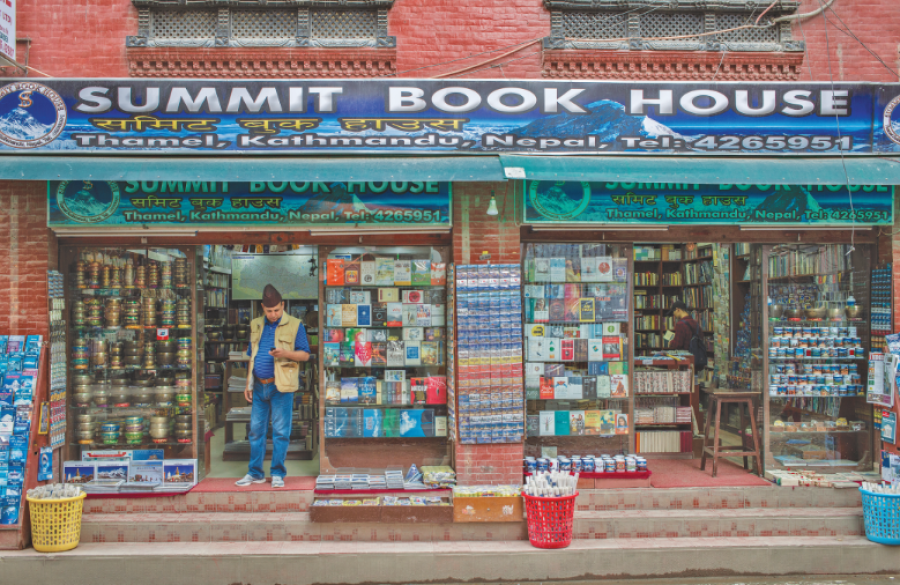

Book imports passed the billion-rupee milestone in the last fiscal year, according to the central bank.

Subin Adhikari

Prem Prasad Sharma used to sell picture postcards to tourists before opening a bookstore named Books Mandala at Lakeside, Pokhara in 1991.

Business was good and he was able to open another outlet at Baluwatar, Kathmandu. Books are stacked floor-to-ceiling at both his shops.

Sharma's bookstores are among the largest in Nepal, and they have more than 45,000 followers on Instagram. His son Saurav Sharma now runs them.

“The book business is growing sharply in Nepal. The boost came after the Covid-19 pandemic. As people stayed home for a long time during the lockdowns, they turned to reading books,” he said.

"Dependable and faster internet service helped sellers to advertise their books digitally. People bought books online during the Covid period. Other supporting infrastructure such as digital payment, cash on delivery and improved delivery systems also propelled the growth of online book stores."

Literature festivals were frequently held in different cities, and this also led to a growth in the number of readers.

Sharma estimates that book sales swelled by 20 to 25 percent during the Covid period compared to pre-pandemic times.

Rajesh Gajurel of Nuwakot launched New Road Book Store in Kathmandu in 2001. Initially, he used to sell newspapers and magazines. In 2005, he started selling Nepali novels too.

Gajurel said the book business really took off after the publication of Palpasa Cafe by Narayan Wagle in 2005.

“If we look at recent trends, sales of English books have skyrocketed in the past two to three years,” said Gajurel.

The English-speaking generation is on the rise. The reading culture is increasing among millennials as English is the most common language on the internet, according to booksellers.

“Before Covid, I used to sell 50-60 books a day. Now, daily sales have quadrupled to 250 copies,” said Gajurel.

As demand started growing, New Road Book Store opened a second outlet in Pokhara two months ago. It supplies books to 15-20 online stores, most of them operated by students as a part-time business.

Official data also shows that book imports have been rising. According to Nepal Rastra Bank, Nepal imported books worth Rs792 million in the fiscal year 2019-20 before the pandemic started.

The government imposed the first nationwide lockdown from March 24 for a week and suspended all international flights from March 22. It kept extending the lockdown as the virus outbreak showed no signs of abating.

Imports came to a halt during the lockdown as all international borders and flights were shut down. As a result, the import of books and magazines dropped by 31 percent year-on-year to Rs545.4 million in fiscal 2020-21.

The book market subsequently started to rebound. In fiscal 2021-22, books valued at Rs984.8 million were imported from India alone, up 81 percent from the previous year, as per government statistics.

Book imports kept growing and passed the billion-rupee milestone in the last fiscal year. According to the central bank, Nepal imported books and magazines worth Rs1.03 billion in the first 11 months of the last fiscal year 2022-23 ended July 16.

As the book business expands, concerns over book piracy have grown too.

“The increase in book sales has attracted pirated copies in the market,” said Likhat Prasad Pandey, president of the National Booksellers and Publishers Association of Nepal. Some readers resort to not-so-ethical practices like downloading PDF versions from the internet or buy hard copies on the grey market.

“The purchasing power of the people has decreased lately due to slowed economic growth. Therefore, the market is flooded with pirated copies as they are available at a cheaper rate,” said Pandey.

Traders say that pirated copies are usually sold by unregistered online stores mostly operating through social media platforms.

“Pirated copies can be bought for half the price of the genuine product. Book sellers who deal in the genuine product on a tight profit margin are having a hard time,” said Sharma.

Both authentic books and pirated copies come to Nepal from India.

Due to the availability of cheap raw materials and labour, India is home to around 24,000 book publishers making it among the top six publishers in the world and the second largest producer of English books.

According to Indian media, the publishing industry loses around 25 percent of its revenue to piracy.

In Nepal, brick-and-mortar bookstores have been hit the hardest by book piracy.

The National Booksellers and Publishers Association says there are more than 10,000 brick-and-mortar bookstores in the country, and their life has been made hard by online stores selling pirated copies.

“These bookstores that have high overheads in the form of staff salaries, rent and taxes have suffered the most from pirated copies; but for students and youngsters who are the major customers, authentic copies are way too expensive,” said Gajurel.

Pirated books are often made using low-quality raw materials to keep prices low, and have issues such as weak binding, missing pages and unclear text.

In some cases, the publishers themselves publish cheaper versions of their books for readers in South Asia as they have low purchasing power.

But in many instances, underground publishers bring out pirated versions of best selling books and supply them in the market at a fraction of the price of the genuine product, industry insiders say.

According to Pandey, there are thousands of pirated copies of more than 600 titles in circulation in the Nepali market.

“Customers often buy these books lured by the heavy discount, only to regret later when they find that the quality of the book is not what they had expected,” said Sharma.

He thinks that publishers must lower their profit margin to make the books affordable to students so they will be discouraged from buying counterfeit products.

8.26°C Kathmandu

8.26°C Kathmandu