Culture & Lifestyle

‘Dokh’: A film that took 10 years to make, but no one watched it in cinemas

The making of ‘Dokh’ is a stuff of legend, but the film’s box office failure is an alarming sign for Nepali films that aim to be unconventional.

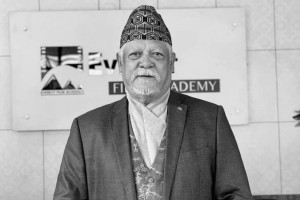

Abhimanyu Dixit

At the time of writing this article, ‘Dokh’, Anup Baral’s latest film, is no longer running in Nepal’s cinema halls. The film was pulled off from the cinema halls before it could even complete its first week. The reason—the audience didn’t show up. The film was released on July 8, and I watched it on July 12, in a near-empty theatre. The only other audiences in attendance were people from the entertainment industry—professional filmmakers and theatre personalities.

This was an utter shock to me because the story of the making of ‘Dokh’ is a stuff of legend. And over the last 10 years, I have developed a soft corner for this film.

I first heard of the film in 2013 when Rajan Kathet won the ‘New Nepali Cinema Script Writing Competition 2’ for ‘Dokh’. Anup Baral, the competition’s judge, had announced that he would lead the project as director and turn the script into a Nepali feature film.

The next announcement of ‘Dokh’ was at a 2015 press conference. Baral, also a veteran theatre director, was helming a jumbo team for his second feature film. Besides 30 or so technical crew members, over 20 actors were introduced at the press conference itself, and it was announced that more actors would join upon reaching the shooting location, Bhojpur. These actors were trained in Nepali theatre and were looking to prove their mettle in their debut film.

This was very exciting news for Kathmandu’s film and theatre community at the time. We couldn’t wait to watch the hyped film. Little did we know that we would have to wait for seven years.

In April 2015, when a devastating earthquake struck Nepal, Dokh’s shooting unit was filming in Bhojpur. The disaster forced the film’s production team to halt work for two years. After the two-year hiatus, Baral, determined to complete shooting, convinced all the cast and crew to rework. Almost everyone agreed, that too without additional payment.

“I am lucky to have a passionate team who love their craft,” says Baral.

The team managed to complete filming in 42 days. But the editing and post-production work would take another five years.

A close English translation of the word dokh is a curse. The ‘Dokh’ film unit was determined to lift their own dokh to release the film, and they spent almost a decade making that happen. A decade is a long enough time for many of us to lose patience and move on to other projects, but this was not the case with those involved in the making of ‘Dokh’. The team stuck to their belief and spent almost a decade completing the film.

However, making a film with great intentions does not mean it will be perceived accordingly by movie-goers. The film was not well received by Nepali audiences, which resulted in the movie being quickly pulled off from cinema halls.

When asked why he thinks the audiences didn’t turn up to watch ‘Dokh’, Baral says, “People believed that ‘Dokh’ was just another conventional Maoist insurgency film. Those films were structured as mainstream films with heroes, heroines, songs, and dances. Because of this preconceived notion, many didn’t even go to the cinema halls.”

‘Dokh’ doesn’t have a mainstream story. The film begins with Ronit (Manish Niraula) arriving in Salle village to work as a primary school teacher. As he explores the village, he meets a variety of characters—the menacing Maoist commander Sangeet (Suraj Malla), who leads a unit of armed men and women; Patre (Lokmani Sapkota), a Maoist sympathiser; Ghanashyam (Maotse Gurung), the village chief; and Rukki (Deeya Maskey), who runs a local bhatti. The village also has a group of rowdy young football hooligans led by Naike (Roy Div).

One day Naike and his group of friends assault a local from the neighbouring Bhakunde village just because the latter entered a community forest controlled by Salle village. This results in conflict between the residents of Salle and Bhakunde. Sangeet then announces that the matter will be resolved only after a football match between Salle and Bhakunde.

Based on the trailer, I, too, expected the film to be conventionally modelled as a political sports drama like ‘Lagaan’ (2001). Traditionally, these stories would focus on team building and winning the football match. However, Baral and writer Kathet use football as a Macguffin. The football match is interchangeable. It can be replaced by any other event, and the story’s outcomes remain the same.

Instead, the story of 'Dokh' is about revenge. Ronit’s father was killed by Maoist insurgents, which fills him with hatred toward the group and their ideology. This hatred instigates a slew of events affecting the lives of people Ronit interacts with. Finally, all events culminate in a finale where no one gets anything.

However, the film’s screenplay and editing do not support this clear line of thought. Instead, the film tries to weave in multiple characters’ perspectives and stories, making many key moments appear underdeveloped. For example, Naike is shown to be very antagonistic towards Ronit, with Naike’s anger peaking with every scene. Suddenly, Naike starts respecting Ronit, and you are left bewildered by the transformation.

Baral also agrees here. “At first, the film’s total runtime was two hours and 40 minutes, which is a very long runtime. We had to cut it to around two hours, which affected the film,” says Baral. “In future screenings, we plan to show the longer version to the audiences for the full story experience.”

On the technical side of things, Baral’s film is applaudable. Uttam Neupane’s sound design stands out, and he embellishes the outdoor scenes with a constant breeze, or sounds of birds, while small details are never amiss in the indoor scenes. Sailendra D Karki’s cinematography is also commendable. You will find clarity and well-lit scenes. I am not fond of the excess use of close-up shots to tell a story. However, Karki is consistent in his approach. Baral’s young actors look believable within the story world. Of the 20 or so cast members, Roy Div, Suraj Malla, and Manish Niraula stand out to me. All three are young actors with great potential; I look forward to their newer projects.

‘Dokh’ is not a sequel, remake, part of a series, or a mainstream conventional film. Audiences not showing up and not giving films like these any chance should be a worrying sign for the Nepali film industry. In recent times, audiences haven’t shown up in cinemas for unconventional films like ‘Chiso Ashtray’ and ‘Chiso Manche’, both of which failed miserably at the box office. Film pundits cite competition of international films, people wanting to watch movies for free on YouTube, and post-pandemic problems for audiences not showing up in cinema halls.

Baral also believes that for unconventional Nepali films to succeed, it is essential for film exhibitors to be more considerate. He says, “I understand Nepali theatres need a minimum number of audiences to run a single show, but I really hope exhibitors can be more accommodating.” But Baral hasn’t lost hope. He aims to exhibit the film internationally and maybe re-release it in Nepal with better marketing. Baral says, “For marketing, we spent less than Rs 700,000, which is very little. But we have learned from this, and we are now contemplating whether to re-release the film again.”

Recent films like ‘Chiso Ashtray’, ‘Chiso Manche’, and ‘Dokh’ are important case studies for the Nepali film industry. These films aim to be different and unconventional, which is much needed if we want to see Nepali films transform. Policymakers in Nepali cinema and various film-related professional organisations should also start looking into it.

More unconventional films have already announced their release dates. ‘Pani-Photo’ is releasing on July 29 and ‘Prakash’ and ‘Radha’ are releasing on August 26. Time will only tell these films’ commercial future. For now, and for the sake of Nepali cinema, we can only hope audiences will show up to watch Nepali films.

Dixit is a filmmaker, film educator and film campaigner based in Kathmandu.

20.72°C Kathmandu

20.72°C Kathmandu