National

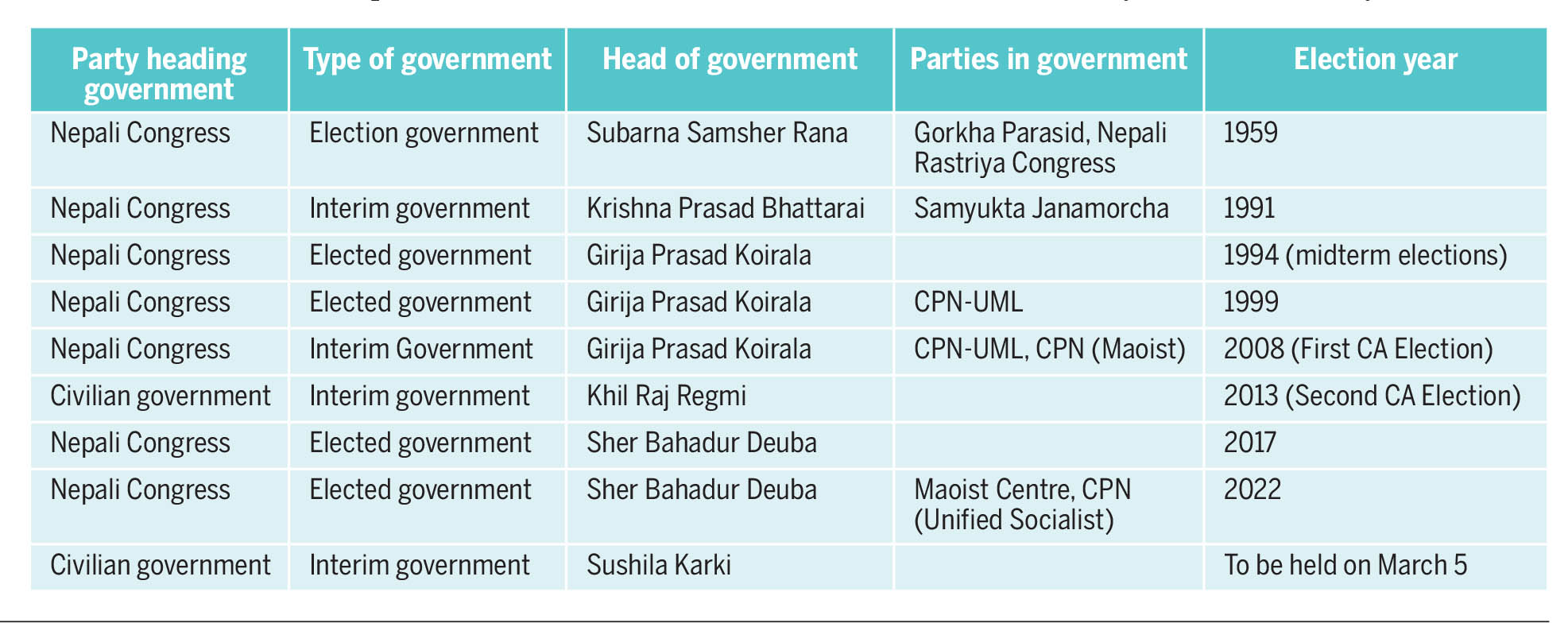

Nine parliamentary elections, none overseen by a communist-led government

Analysts see no design except that rival parties did not want Maoists to hold 2013 Constituent Assembly elections.

Purushottam Poudel

Nepal is set to hold its ninth democratic parliamentary vote on March 5, continuing a long but oft-turbulent history that began with the country’s first general election in 1959.

Of the nine parliamentary elections held so far—including the upcoming one—seven have taken place under governments led by the Nepali Congress. Two elections have been conducted by non-partisan ‘civil’ governments: the second Constituent Assembly (CA) election in 2013 under then-chief justice Khil Raj Regmi and the forthcoming election under another former chief justice, Sushila Karki, who assumed leadership following the September Gen Z uprising.

Overall, four parliamentary elections have been overseen by elected governments, while four have been conducted by interim administrations and one by an election government.

Despite communist parties consistently securing a significant share of the vote—often close to 40 percent in recent elections—no government led by a communist party has held a parliamentary election.

In the 1999 general election, for instance, the Congress-UML coalition government led by Girija Prasad Koirala conducted the polls. The UML was again part of the governing coalition during the first Constituent Assembly election in 2008, which was also held under Koirala’s leadership. Although communist parties were represented in these election-time governments, they did not lead them.

Krishna Pokhrel, a political science professor and left-leaning analyst, says this pattern reflects political circumstances rather than institutional exclusion.

After the first Constituent Assembly failed to deliver a constitution and was dissolved, Maoist leader Baburam Bhattarai was prime minister. However, when major parties—including the Nepali Congress and the UML—refused to participate in elections organised by the Maoist-led government, a non-partisan administration headed by Chief Justice Regmi was formed to conduct the 2013 elections.

“Usually, the government that dissolves the House is responsible for holding elections,” Pokhrel said. “But after the first Constituent Assembly collapsed, the refusal of other major parties to join the process led to the formation of a civil government.”

Pokhrel also traces the roots of political distrust to earlier electoral experiences. During the 1994 local elections, Lokendra Bahadur Chand of the Rastriya Prajatantra Party was prime minister while UML leader Bamdev Gautam served as home minister. Gautam was accused by political rivals of attempting to influence the election in the UML’s favour—allegations that, according to Pokhrel, contributed to the Nepali Congress’s long-standing reluctance to participate in elections conducted by communist-led governments.

Pokhrel says democratic parties, particularly the Congress, have long harboured concerns that communist parties could try to tilt elections in their favour if they were in charge of the government during polling.

“If there were accusations that communist parties influenced elections even by leading the home ministry, one can imagine the level of apprehension about what might happen if they led the entire government during elections,” Pokhrel said. “That fear among parties representing democratic ideology is a reason why elections have not been held under a communist-led government.”

This history of mistrust, he argues, helps explain why Nepal’s parliamentary elections have repeatedly been organised either by Congress-led governments or by neutral interim administrations rather than by communist-led ones.

Ram Karki, a communist leader who spent many years in the Maoist Centre and has joined the newly formed Progressive Democratic Party, says the Nepali Congress’s credibility has been a key reason why it has often led election-time governments.

According to Karki, even when coalition partners take turns leading the government, there is usually a shared preference among political parties for the Congress to head the administration responsible for conducting elections.

Before the parliamentary elections held in 2017, the government was led by Maoist Centre chair Pushpa Kamal Dahal. His administration completed the first phase of local elections that year and then supported the formation of a new government under the then Congress president Sher Bahadur Deuba to conduct the remaining local polls and the subsequent parliamentary election.

While in the Deuba-led government, the Maoist Centre had decided to form an electoral alliance with the UML for the parliamentary polls. Despite the two major communist parties contesting together—and concerns within Congress that the electoral outcome might not favor it—the Congress-led government went ahead and held the elections on schedule.

Similarly, the coalition led by UML chair KP Sharma Oli, which governed the country until the Gen Z movement, had continued in office for some time, under an agreement reached between the Congress and the UML in July 2024. The Congress would have led the government next, and conducted the periodic parliamentary election in 2027.

Why, then, has the Congress earned a level of trust in conducting elections while communist parties have not?

Karki believes this is closely linked to political ideology.

“Several countries guided by communist principles have no periodic elections, whereas regular elections are a defining feature of democratic systems,” Karki told the Post. “This has helped the Congress build public and political confidence in its role as an election organiser in Nepal.”

Nepali Congress observer Jagat Nepal says many elections in the country have been conducted under Congress leadership because the party is widely seen as a trusted political force, both domestically and internationally.

16.13°C Kathmandu

16.13°C Kathmandu