Movies

Straight from the heart

Nabin Subba’s 2001 film is a rare example of a nuanced, thoughtful and culturally sensitive film.

Urza Acharya

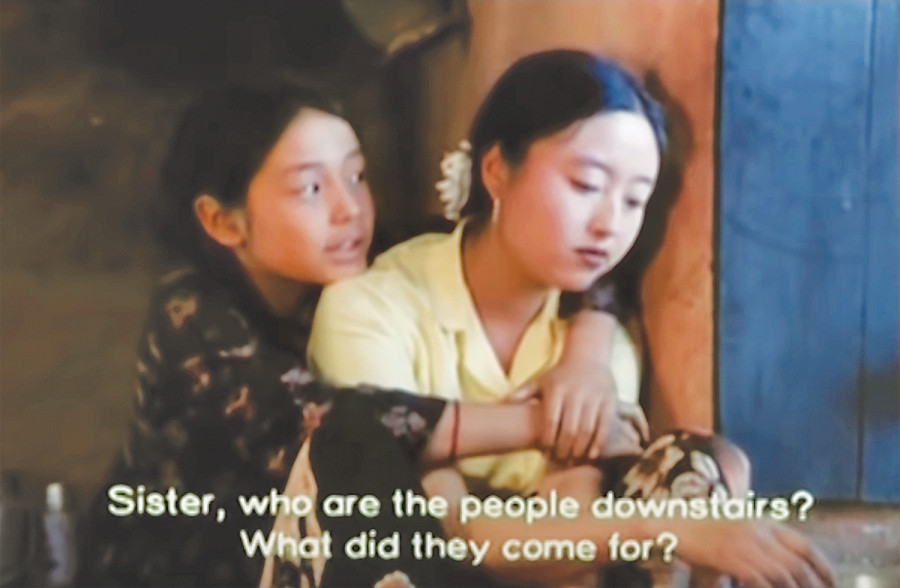

Numafung is visual poetry. It is gentle and nuanced. Steering away from most, if not all, the cliches of Nepali cinema—the long fights, the dance and song sequence atop a hill, the heavy monologues—Numafung provides the viewer with a ‘slice-of-life’ window into the lives of a farming Limbu family somewhere in Eastern Nepal. The film has a mixture of Nepali and Limbu languages—with older characters speaking Limbu language, whereas the young opting to speak Nepali.

Directed by Nabin Subba, the film was released in 2001. Based on a story by Kajiman Kandangwa, called ‘Karobar ki Gharbar’, it is written in Limbu language and features Anupama Subba, Niwahangma Limbu, Prem Subba, Ramesh Singhak and the late Alok Nembang as the lead actors.

Told through the eyes of Lojina, a young Limbu girl who lives with her mother, father and big sister, Numafung (or Numa), the plot of the film revolves around the two marriages of Numa—first to the young and kind Ojahang and later to the temperamental and often violent, Girihang.

Divided into five chapters, Lojina acts as a surrogate for the viewer—quietly but carefully observing all the major incidents that affect her big sister’s life: two forced marriages, her domestic struggles, a miscarriage, and an elopement.

What makes Numafung interesting is not just the dramatic things that happen on screen. In fact, it’s very easy to make a woman wail, cry and feel pain on screen. There’s a sort of plague that’s spread rampantly in Nepali cinema and worldwide, and it's called ‘fridging’—a plot device in which a woman is murdered, raped, or subjected to other forms of abuse only to give a male protagonist a cause to start fighting their enemy. And the sad reality is that this is something that Nepali directors and screenwriters rely on way too much. This is not the case in Numafung. The ‘heroes’ who were violent and cruel—like Girihang—don’t get catharsis.

Moreover, Numafung helped me learn about a totally different culture from mine. It is not a stretch to argue that the mainstream movie scene is filled with Khas-Arya stories. It’s rare to see main protagonists from ethnic minorities. Even if they are in the film, their characters are marred with stereotypes and are often the butt of the jokes.

I learned from the film that the Limbu community is more open in many ways. Lojina is given ‘Tongba’ (a drink made from fermented millet) to drink whenever she visits her sister. When Numa becomes a widow after the death of her first husband, she can start a fresh life. In the haat bazaar (local weekly market), the young girls and boys were shown freely mingling with each other, flirting and dancing without any worries of being reprimanded.

Similarly, both of Numa’s mothers-in-law are sympathetic and powerful women who treat Numa kindly—refusing to follow the ‘cruel’ mother-in-law trope that’s all too common. Numa’s father isn’t a roaring patriarch, one that is violent or cruelly authoritative. It really is quite refreshing to see how, even in 2001, Numafung abandoned all tropes that afflict Nepali cinema—instead, opting to be a film that is authentic, honest and culturally sensitive.

Though one can argue that the Limbu community is perhaps more open than, say, the Khas, they are still inherently plagued by patriarchy. The concept of ‘sunauli-rupauli’—wherein the parents give their daughter's hand to the suitors who can provide the most wealth and gold, as well as the idea of ‘jari’—payment typically made by the man who ‘steals’ the wife from the husband see women as a commodity that can be exchanged as currency. There is a scene where Numa asks her mother, “Do you take me for an object to be traded?”

But the beauty of Numafung is that Numa and all the other women in the film are not passive receivers of patriarchy. They speak up, and they reprimand men that misbehave. In a scene, Lojina spits on Girihang’s plate before giving him the food and slams the plate on the floor right in front of him. This can be seen as a form of ‘disguised resistance’ wherein the oppressed find covert and subtle ways of responding to domination.

The crux is that there simply aren’t enough movies like Numafung. Movies that treat their characters (especially the female characters) with respect, making them complex human beings and making them real. Even two decades after its release, Numafung is still relevant. The patriarchal maladies faced by Numa and the women in the film continue to haunt women even today. In her review of the film for Himal Southasian, Seira Tamang, a political scientist says, “From the widening of the frame to accommodate nuances of Limbu culture, to the underlying perceptiveness with regard to gender relationships…the multiple sensibilities which inform this film are extraordinary.”

Numafung is a film that should be watched by everyone. Nabin Subba, the actors and the entire film crew have made a truly beautiful film that’ll leave you comforted and with a lot of things to think about. A new film set within the Limbu community titled ‘Jaari’— directed by Upendra Subba and starring Dayahang Rai and Miruna Magar— will hit theatres on April 14. One can only hope that ‘Jaari’ will be able to match the brilliance of Numafung.

Numafung

Language: Limbu and Nepali

Subtitle: English

Duration: 1 hour, 48 minutes

Director: Nabin Subba

Cast: Anupama Subba, Niwahangma Limbu, Prem Subba, Ramesh Singhak and Alok Nembang

Released: 2001

14.09°C Kathmandu

14.09°C Kathmandu