Columns

Vocabulary augmentation: Then and now

We might need to be cautious before prescribing what would work for digital native students.

Pratyoush Onta

In the Mangsir 2082 BS issue of the monthly Shikshak magazine, writer Ananta Wagle has written an article on classroom techniques to expand the vocabulary of school children. He starts by saying that mastery of vocabulary allows individuals to be both effective communicators and better readers. He then describes various techniques: Today’s word (discussing a new word each day), finding related words, finding synonyms and antonyms of words, word bingos, and creating a word list to hang on the classroom wall. Other techniques that Wagle mentions include acting out words, filling in the blanks in brief passages, writing short stories using specified words and creating personal “dictionaries” in handwritten notebooks. Reading this article made me both nostalgic and anxious.

Nostalgia

Reading Wagle's article evoked memories of my initial attempts to learn English words, more than half a century ago. As a grade II student at St Xavier’s School (StX) Jawalakhel in 1972, we had to study English spelling. This meant memorising long lists of words that our teachers handed out. I can’t recall the rationale provided by our teachers that year. But in higher grades, our English teachers used to tell us that we had to learn the spellings and meanings of new words to expand our vocabulary so that our command over the English language—both our levels of comprehension while reading and our ability to express ourselves while writing—would improve. In other words, the logic they used was exactly the one mentioned by Wagle in his article. We were also encouraged to own and use a dictionary.

An English spelling contest was held regularly at StX. I do not have a copy of the spelling list given to us that year, but I have an honour card dated May 29, 1972, which states that I secured third place in the competition. I do not remember the exact format of the contest. Maybe everybody took a written spelling test based on which some students who had done well were selected for later rounds of oral competition. Or possibly every student stood up in turn to spell a random word chosen from the list. That student would first pronounce the word, spell it and pronounce it again. The following student had to say whether that rendition was accurate or not. Incorrect spelling or judgment eliminated a student from the competition.

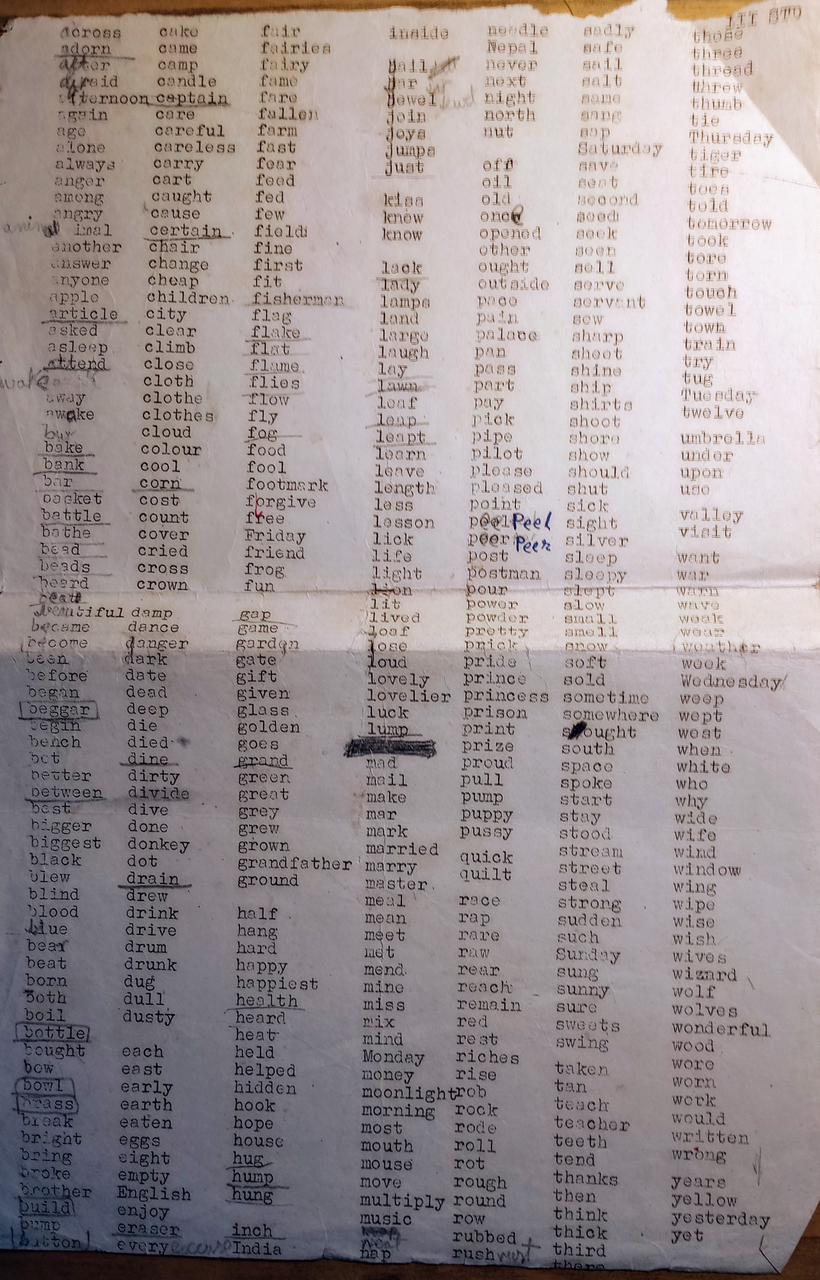

“[A]cross, adorn, after…yellow, yesterday, yet”. The list of about 500 words we had to memorise for the English spelling contest in class III contained these words (see the image below). I don’t remember the method we used to memorise the spellings and learn the definitions of the words in this list from 1973. Maybe we wrote their meanings on one page and our own sentences with those words on the facing page of a notebook. In class VI in 1976, we were definitely doing that: I still have my notebook.

I don't recall if we had Nepali spelling contests in classes II and III. Nepali was not given as much priority at StX since it was an English-medium school. But the New Education System (NES) announced in 1971 eventually changed that. Starting with the 1972 academic year, the NES was executed in different phases in the then 75 districts of Nepal. Its third phase encompassed 15 additional districts including all three districts of the Kathmandu Valley. Hence in 1974, the NES curricula was implemented in classes one, four and eight of all schools located in Lalitpur district. As students of class four, all of our textbooks, except for English, were now in Nepali; we had become part of the first cohort as StX transitioned to a Nepali-medium school. Now Nepali spelling got its own list, which that year included about 210 words. During the higher grades, our teachers used virtually every technique mentioned by Wagle to help us augment our vocabulary.

Anxiety

However, reading Wagle’s article also made me anxious. Twenty-five years ago, I would not have felt that way. Then I would have said with full confidence that, both the fundamental logic and the list of techniques he describes, work. My confidence would have been derived from my positive experiences at StX and those of the same cohort of students from other schools. Those students, myself and Wagle, belong to the generation of students who finished school years before the era of mobile phones, and whose efforts to augment our vocabulary primarily involved printed resources.

In 2025, I am still confident that the fundamental logic is sound; namely, individuals with command over a large vocabulary are both better communicators and readers. However, I hesitate to say with any confidence that the techniques that worked for us all those years ago also work for digital native students. I have not seen my 17-year-old son use a printed dictionary in recent years. He and fellow-students of his age take the internet, smartphones and social media for granted. These digital resources have been integral parts of their lives since their earliest childhood. They learnt to type into smartphones with autocorrect from the time they became familiar with the alphabet. So, they have a different relationship with spellings.

In our case, we had to memorise spellings because otherwise we could not handwrite the relevant words correctly. Or when we encountered unfamiliar words in our readings, we had to run to a dictionary and turn its pages (I still do that occasionally). But digital natives are exempt from these exertions. Spell checks and autocorrect features on their smartphones (and computers) mean that they need only be acquainted with words and not their exact spellings. When they encounter difficult words, they can copy-paste and consult an online dictionary (or an AI assistant). When they want to expand their vocabulary, the thesaurus is similarly one click away. In other words, the correct spellings and usage need not be lodged in their minds following memorising routines that we exercised.

Hence, the techniques for them to learn spellings must be somewhat different. I assume various types of spelling apps with audio features and digital games would be perhaps more pertinent for today’s school kids. Watching videos with subtitles might also come in handy for visual familiarisation with difficult words. There must be other digital ways recommended by expert practitioners.

The bottom-line argument of this column goes well beyond vocabulary and spelling. Those of us who are middle-aged need to be more cautious and less confident about prescribing what works for members of Gen Alpha. They are living in a world whose coordinates are very different from those we know from our lives. We might need to learn a lot more before prescribing what would work for them.

20.11°C Kathmandu

20.11°C Kathmandu

.jpg&w=200&height=120)