Columns

Nation-building isn’t a one-man game

Redefining leadership requires dismantling and reshaping centuries of narrative upheld by the political elites.

Aakriti Ghimire

Democracy is young in Nepal—it turned 17 in 2025. I am 26. In these shared years of growth, the year 2022 marked a sharp political turn where two faces from non-political backgrounds won with a landslide victory. One became a mayor, the other a member of parliament. While the hope instilled felt new, it still operated under the recycled concept of a hero coming to save the day.

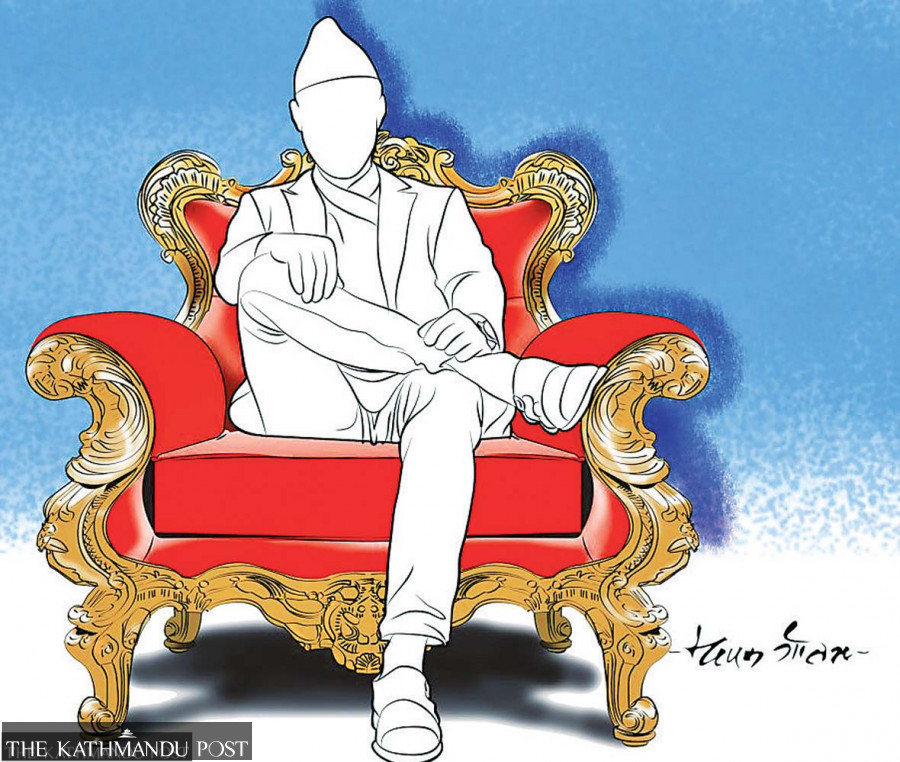

The faces changed, but the existing political culture of the deification of a leader did not, and sadly has not. Post September 8, too, despite the changed political mandate, Nepal continues to seek a sole redeemer, which may only pave the way for another KP Oli to be born if the understanding of ‘leadership’ is not redefined.

Political culture of deification

Men in power have always portrayed themselves as the solution for everything. Posters of Oli with his hand up, Pushpa Kamal Dahal with his fists clenched, Balen and Rabi’s namastes with a national flag over their shoulders and an evocative song in the background, all with the same message: The hero is here. This promotion of one strongman continues to benefit them.

Unsurprisingly, this remains true even for the young voters, who have neither experienced monarchy nor feudalism. The Gen Z-ers and Gen alphas are being packaged in the same political culture with a new branding of ‘alpha/sigma archetypes’ that promote hypermasculinity. As a consequence, even when the new political faces act irrationally, their stubbornness is instead glorified because the public relates to these new faces as their dais and bhais.

Deliberate disenfranchisement of the public

In the last decade of Nepal’s flirtation with democracy, our search for one saviour has diverted priorities from policy to personality. This personality-focused leadership becomes a breeding ground for a dangerous followership; unconditionally devoted, to the extent that the followers are unable to hold their leaders accountable, and instead threaten ordinary citizens who raise questions or criticise their leaders’ actions. The followers are expected to juggle multiple hats: From running an online army and offline gangsta fights, to ensuring regular recruitment within their clan. Even when their leaders create undue pressure against university vice-chancellors, disregard Supreme Court orders, brutally harass street vendors, threaten the caretaker Prime Minister to resign, or demand the interim government make changes to the constitution, the followers sold on their leaders’ brands relentlessly defend all of their actions. In a cult-like fashion, every political party (and dai gang) creates an identity that each member carries, from classrooms to tea stalls to government offices to ward offices to trade unions to Gen Z groups. Consequently, the public is disenfranchised.

This disenfranchisement is deliberate. The culture of deification isn’t just a personal preference; it is a systemic issue that emerges, benefits and perpetuates the existing structures of inequalities. Despite the opportunity to sow seeds of participatory democracy through curriculum in schools and universities, the negligence to do so evidences the old guards’ intention of ensuring the Nepali citizenry is unable to ask questions. Expecting a saviour then becomes time and cost efficient for those who need to spend the majority of their time in economic activities, be it in the field or kitchen. Many do not have the luxury to think, talk and participate in active politics.

For those who can afford to be engaged, they are forced to hold on to some leaders’ clans to access even the most basic services that are guaranteed by the law. Many students in universities pick student unions with ties to major political parties to access networking and internship opportunities. Teachers are forced to seek partisan support to access any form of transfers. What should be institutionally guaranteed in a fair, predictable and transparent manner has been made opaque and contingent upon becoming a jholey. In such a case, the public becomes subjects of the rulers through votes, likes/shares and necessity borne out of socioeconomic conditions. This ultimately perpetuates the same political culture of herofication. The power, thereby, remains with the political elites.

This political culture of deification can be dismantled through political education, but access to this form of information is also limited. For instance, the majority of voters are unaware of the legally mandated responsibilities of members of parliament, parliamentary committee chair or even a deputy mayor. Then, how would a voter vote for the right candidate? This is a deliberate strategy employed by the then monarchs, then feudal lords and now the old guards. Despite being the flagbearers of democracy, the old guards never led the discussion on how to do democracy. In fact, these saviours disillusion the public into thinking they are the only solution, fabricating a dependency on them.

The need to redefine political culture

At this moment, as new leaders rise post Gen Z protests, many have already begun amassing followers. Without a drastic shift in the political culture of accountability, the dai and bhai culture will birth another brand of jholeys, yet again. Yet, this conditioning is reversible, and it requires both an institutional intervention and a collaborative citizen-led intervention.

An institutional solution, in the short term, can be implemented through the Election Commission itself. Voter awareness can be extended to include information about the state apparatus, the functioning of the government and the job responsibilities of people’s representatives. If the public is aware of how decisions are made, who contributes to what, when, and how, then the public can identify where the problem lies— whether in capacity, knowledge, infrastructure, resource, bureaucrats, consultants, process, or leadership itself. And by translating to local languages, sign languages and providing it in an age-appropriate format, it could empower the voters to assess the leaders’ capabilities. In the longer run, political education has to be embedded in the curriculum across schools and universities, particularly focusing on developing critical thinking and analytical reasoning skills. An active and informed citizenry is critical to democracy.

However, given the upcoming elections in March 2026, an immediate need of the hour is a national discussion on ‘leadership.’ Political actors, civil society members, artists, musicians, teachers, and the public can play a critical role in engaging in discussions nationally to ask the long-overdue question, ‘Can one individual save Nepal?’ The traditional media and YouTube journalists also need to shift their questions from Who is your one leader?’ to the Gen Z groups and instead ask ‘What kind of values do you seek in your leaders?’

Redefining leadership requires dismantling and reshaping centuries of narrative upheld by the political elites.

The discussions need to penetrate homes, social media, classrooms, tea stalls and every social circle. And if a mass discussion sounds impossible, we can take inspiration from the #nepobaby trend that communicated class inequality in a language that Gen Z understood through simple images and evocative music.

Leadership isn’t about giving speeches and riling up the crowd. It takes multiple forms—be it in brainstorming creative expressions, ensuring inclusivity and meaningful participation of diverse voices and identities, managing logistics, communications, drafting new policies, conducting research, asking the right questions, and even admitting one’s mistakes, apologising and taking accountability. It is about empathy, accountability, competence, humility, integrity and collaboration.

Unless the public is made capable of recognising that developing a nation requires many leaders sharing roles and responsibilities, we will keep losing decades in hopes of finding that one saviour.

Until the public doesn’t realise and exercise the power they yield, democracy will just be a noun. It falls upon all of us to ensure that democracy becomes a verb, an action word.

18.12°C Kathmandu

18.12°C Kathmandu