Columns

Seven decades of democracy

There are some people who are imbued with the qualities of good political leadership.

Abhi Subedi

People who participated in some discourses that I presented via Zoom or in-person in the past weeks barraged me with questions of a political nature. That was a unique experience for a non-political writer. When I reminded them that such sessions should be organised with politicians and related people, they said they were cheesed off with the political gaffes made by party leaders. Knowing well that I was not the right person to talk with about political subjects, the Sushil Koirala Memorial Foundation invited me to put my views under the rubric "Seven decades of democracy: Achievements and challenges" on February 19.

I felt I was confronted with the familiar left-right binary, also explained by Francis Fukuyama that I allude to later, in Nepali politics, when the organiser of the programme Atul Koirala of the foundation and the participants wanted me to open up the colloquium. The title sounds as though the country has experienced a smooth seven decades of democracy. History never travels on a smooth path, not least of political orientations. In Nepal, too, democracy did not traverse a smooth path. But what is very remarkable about Nepali democracy is that it has always made its presence felt.

Confusing situation

I was struck by a satori-like knowledge in a flash, which was that confusions and bewilderments are piling up in the realms of politics, governance and human relationships in this country in recent times. There is a growing desire to discuss the alternatives. There is a sense of quest for alterity to explain the current questions about the confusing situation in the field of democracy and people's role in general, and the battles of identity in particular. I realise that this state of political confusion has some advantages too. That is, we have begun to realise that the canons that we have built over a certain period are slowly being rejected. As a result, we have opened our minds to alternative thoughts.

For the colloquium, I used BP Koirala's famous statements from his court testimony during his trial conducted in a special court from April 29 to May 17, 1977. BP Koirala said in his testimony that the day king Mahendra dissolved the first democratically elected Parliament of the people on December 30, 1960, and jailed its prime minister, parliamentarians and others, the Nepali people's prestige was directly assaulted, and they were humiliated. I put that to see how democracy functioned, to see how the achievements of the people's revolutions were institutionalised, and to assess how in different phases of Nepali history, the selfsame subject of the Nepali people's prestige was reiterated. But experience shows that the vision of BP Koirala, to link the ordinary people's prestige with democracy, does not appear to have worked cogently during the seven decades of Nepali democracy.

To theorise the picture of Nepali democracy of the seven decades, I went back to Francis Fukuyama's simplified interpretation of 20th century politics, which he says is "organised along a left-right spectrum". Economic issues remain at the centre. Fukuyama makes a distinction between the perceptions of the left and the right. He says the left demands greater freedom and more equality. That is progressive politics. They work with the workers and trade unions. These parties seek better economic redistribution. Those interested in the government's reduced size represent the other strand of politics, and they want to promote the private sector. But he says in the second decade of the 21st century, the left spectrum has changed; it is defined by "identity" ("Why National Identity Matters", Journal of Democracy, Number 4, October 2018).

Fukuyama's interpretation of left and right politics is straightforward, albeit there is an element of reiteration. We have always understood the Nepali political scenario along with the same simple algorithm. But that simple linearity appears to be creating problems for both political interpreters and art and literature-inclined people. Frankly speaking, the political scenario, especially defined by the left-right binary, does not appear to be functioning properly anymore in Nepal. The present coalition government led by the Nepali Congress under the leadership of Sher Bahadur Deuba may be an eloquent example. This government may collapse if it fails to get the $500 million US grant known as MCC ratified from the House, given the opposition of the two crucial partners in the coalition government, the communist parties led by Prachanda and Madhav Kumar Nepal. The two parties are in a Catch-22 situation because they want to see the coalition continue and challenge its very existence over the question of the MCC. There is no space for repeating the surfeits of discussions on the subject.

To evoke the binary again, the leftist and the so-called democrats have parted ways and come together to herald new periods in Nepali democracy in the seven decades. I am particularly reminded of the comprehensive peace deal between the Maoists and the seven parties signed on November 21, 2006. The binary elements of Nepali politics have surprisingly remained the features of the continuum. These two components of the Nepali political algorithm have now entered a new phase that is influenced by external factors more than ever before. However, we should question whether the binary of the left and right should be deconstructed, seeing the unstable positions of these parties and the emergence of others who represent identities, geographies, cultures and languages.

Dearth of leaders

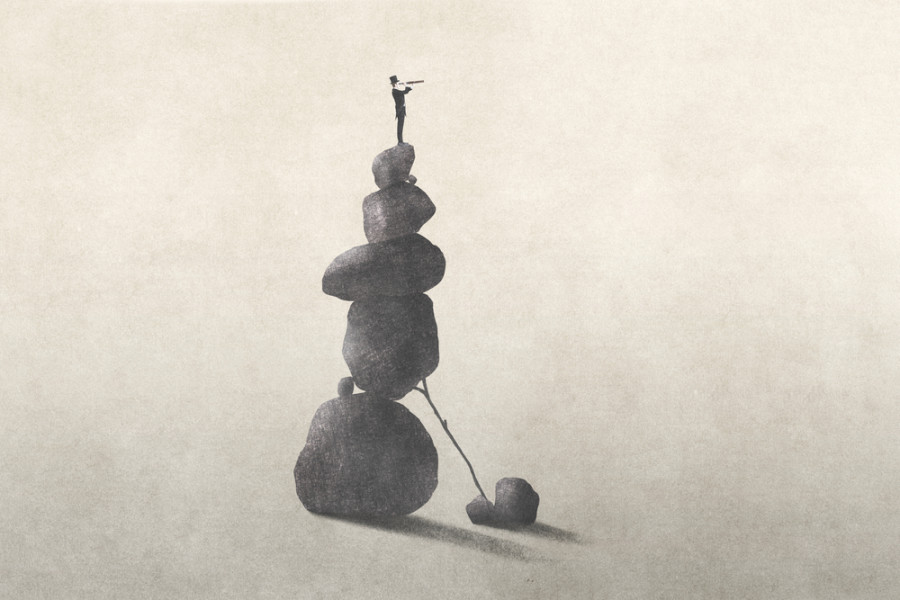

My conclusion was that we are facing entirely new challenges of our democratic heritage. This may be my very personal view. We are increasingly realising that there is a dearth of visionary, creative, and reliable political leaders in our country. Like the characters in well written plays, such leaders should come to fill up an important gap in the political drama. There is no clear way of making up for such ellipsis in politics. That is not our typical problem. It is not just the Nepali nation-state, history shows that other countries in the world, including the powerful ones, too have called and even cried out for such leaders whenever crises loomed. The world is going to experience more challenging moments.

The emergence of a good leader depends on so many factors. The attitudes and policies of neighbouring countries and international conditions play a role in making political leaders of any nation today. In the case of Nepal, my conviction is that there are some people who are imbued with the qualities of good political leadership. Some have dedicated their lives to the cause of democracy. They have suffered jail and hardships for that. And they certainly have good qualities that are necessary to become good leaders. The seven decades of democracy have opened up both challenges and possibilities.

11.12°C Kathmandu

11.12°C Kathmandu