Books

Telling the human story of the Chicken’s Neck

Akhilesh Upadhyay discusses his new book, ‘In the Margins of Empires: A History of the Chicken’s Neck’ and how life in the borderlands is defined not just by power politics, but by memory, movement and ordinary people.

Anish Ghimire

Akhilesh Upadhyay has spent much of his life exploring places where borders shape people’s lives and identities. Born in the eastern town of Bhadrapur, near the Siliguri corridor, known as the Chicken’s Neck, Upadhyay brings a unique perspective to his latest book, ‘In the Margins of Empires: A History of the Chicken’s Neck’.

Upadhyay, former editor-in-chief of the Post, and now a senior research fellow at the Institute for Integrated Development Studies (IIDS), moves beyond the geopolitical spotlight to tell the stories of people living in the borderlands. He examines how global power shifts are felt in small towns and remote Himalayan communities.

In this conversation with the Post’s Anish Ghimire, Upadhyay shares why the Chicken’s Neck captivated him and how his upbringing influenced his worldview.

In your book, you write that you are ‘always subconsciously in a borderland state of mind’. What does that mean?

I grew up in places shaped by borders and movement. I was born in Bhadrapur, a town close to eastern India. And some 40 kilometres away in Siliguri, I experienced many ‘firsts’—my first cinema hall, my first big railway station, and my first beer.

When I went to study in Darjeeling, it was again a transit town for me. It was not just a physical crossing but a personal one—from childhood to adolescence and continually between Nepal and India. Because of this, I have always found it difficult to confine myself to a single political boundary, either in life or in writing. This is what I mean by ‘I am always in a borderland state of mind’.

While writing the book, I was never fixed in one place. Some chapters were written in Kalimpong, others in Siliguri, or Kathmandu, and different parts of India’s Northeast. At times, I was travelling physically; at other times, I was travelling through memory. I often found myself revisiting my childhood and teenage years—places I moved through easily before borders hardened and political tensions grew.

My travels to Tibet also shaped this mindset. While writing, I often felt as if I were walking the streets of Lhasa or Shigatse.

Beyond personal reasons, why did you choose the Chicken’s Neck and the Himalayan borderlands as the subject of your work?

I have always been fascinated by the rapid rise of India and China. China opened its economy in 1978 and India in 1992. Both were once economic backwaters, but over a few decades, they grew far beyond what anyone had imagined. As a student and observer of international relations, I was deeply interested in this transformation and its geopolitical impact.

I travelled frequently to India and also had several opportunities to visit China, particularly between 1992 and 2019. Every time I returned to China, I was struck by how much the country had changed in just two or three years. But what interested me was not only the new buildings or infrastructure. I wanted to understand how society itself had evolved—particularly in the border regions.

We often focus on major cities such as Beijing, Delhi, or Kathmandu. But what about the peripheries—such as Siliguri, Olangchun Gola, or smaller Himalayan towns that rarely make headlines? While major geopolitical stories appear in international or national newspapers, I wanted to know how people in these regions experience growth, power, and politics. Do they feel represented? Do they have agency over decisions made far away from them?

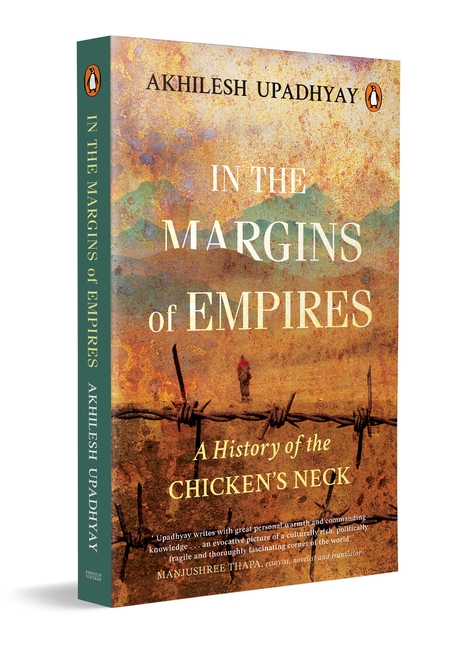

In The Margins of Empires

Author: Akhilesh Upadhyay

Publisher: Penguin Random House

Year: 2025

The book focuses on the eastern Himalayas—eastern Nepal, Sikkim, northern West Bengal, Arunachal Pradesh, and the Northeast of India. I sought to examine how these territories and communities fit within the broader geopolitical theatre, and how shifts in global power affect everyday lives in these regions.

Community identity was especially important to me. For example, in Olangchung Gola, many locals are labelled as Sherpas, although they identify as Walung-ngas. The term ‘Sherpa’ became a convenient administrative label, often imposed by outsiders. While it sometimes helped them find work—especially in mountaineering—it also erased their distinct identity. Many people I spoke to did not fully identify with the label, even though it brought certain advantages.

Your book moves easily between history, politics, and everyday lives. How did you bring facts and people’s stories together?

Many books on the Himalayas are written either by Western scholars or by researchers based far from the region, often in cities like Delhi. I felt it was important to write about the Himalayas from within the region. I speak the languages, understand the cultures, and can travel to places that are often difficult for outsiders to access. That gives this work a different perspective.

Initially, I tried to write like an academic. But I soon realised that this was not my forte. My real strength lies in listening to people on the ground. Over the past five years, and especially while working on this book, I travelled extensively across Nepal’s border districts, the mid-hills, Sikkim, Darjeeling, Kalimpong, and Siliguri–the ground zero of the book.

I would not call this work ‘scholarship’ in the strict academic sense. It is an attempt to tell the story of the region by someone from the region. I do not try to romanticise or glorify the Himalayas. I try to show life there as it is.

What I discovered was that ordinary people are often the best storytellers. To hear them honestly, I had to unlearn many of my own assumptions. Earlier, as a newspaper editor, I often travelled with official delegations to places like Beijing, Delhi, or Mumbai. That came with a certain distance and privilege. Once I stepped away from that role, my real learning began.

I started travelling quietly, without announcing who I was. I did not want titles or introductions to shape conversations. This allowed locals to speak freely. Sometimes, the people I had met earlier had already moved on—as often happens in the Himalayan region, where migration is a constant part of life. That movement itself became part of the story.

These experiences made me reflect deeply on ideas like migration and indigeneity. People have always moved—for work, safety, and survival. So, when do we decide who is ‘indigenous’ and who is an ‘outsider’? This book does not provide fixed answers; rather, it raises questions.

And what stood out during such incognito travels?

The ordinary people. Simple. They were warm, generous, and deeply human. If locals feel you are listening honestly, they will share their best stories. In many ways, they are the real heroes of the book. I am only a storyteller.

My earlier work as an editor did not always allow me time to read deeply or stay focused on a single subject for long. After 2018, however, I entered a more productive phase of reading and reflection, and it felt inevitable that this material would eventually become a book.

Some people played an important role in shaping the project. They encouraged me to examine the Chicken’s Neck region more closely. Amish Mulmi once said to me, ‘You know China well, but what about the Chicken’s Neck? You grew up there.’ At first, I was hesitant. But once I began travelling there with a fresh perspective, it started to make sense.

Having grown up and studied in Darjeeling and spent much of my childhood in Siliguri, the area felt almost like home. That familiarity allowed me to notice small details and local nuances that might otherwise be missed, and it helped shape the book in a more intimate and grounded way.

You’re focusing on everyday stories within big political issues. Did your experience studying in the melting pot of New York in the late ’90s and early 2000s play a role in shaping that approach?

New York changed me in a fundamental way. It is a truly multicultural city. On my commute from Queens to the heart of Manhattan, I would hear 20 or more languages. That everyday exposure to diversity shaped how I see stories.

After 9/11, I spent a lot of time speaking with immigrants and working-class communities—Afghans, Pakistanis, Punjabis, and others—who were suddenly living in fear. One Punjabi taxi driver told me passengers would stop his car and then run away because of his turban and beard. He said he had gone weeks without income and did not know how he would pay rent or send his children to school. The pain in his voice stayed with me.

I was drawn to working-class areas, listening to people whose lives were directly affected by big political events they had no control over. That experience taught me that large political issues—war, terror, migration—are ultimately lived through very personal, human struggles.

What I learned in New York is the same lesson that guides my current work: if locals feel you are listening with honesty and intent, they will open up. Language, culture, and geography may change, but human vulnerability is universal. And that is where the most powerful stories are found.

_________

In The Margins of Empires

Author: Akhilesh Upadhyay

Publisher: Penguin Random House

Year: 2025

_________

Akhilesh Upadhyay’s five book recommendations

Anna Karenina

Author: Leo Tolstoy

Publisher: The Russian Messenger

Year: 1878

I recommend this book for its mysticism. The novel’s starting sentence is perhaps one of the best in the world.

Fatsung

Author: Chuden Kabimo

Publisher: FinePrint

Year: 2019

This novella is magic. Kabimo writes about disillusioned children following the Gorkhaland movement in Darjeeling.

Babbitt

Author: Sinclair Lewis

Publisher: Harcourt, Brace & Co

Year: 1922

Based on a time when the US was seeing rapid economic growth, this novel is the story of Babbitt who, despite being successful, leads a double life.

The French Lieutenant’s Woman

Author: John Fowles

Publisher: Jonathan Cape

Year: 1969

Fowles’s book is experimental. He presents different endings, leaving readers to ponder various outcomes for the main characters.

The Idiot

Author: Fyodor Dostoevsky

Publisher: The Russian Messenger

Year: 1869

Literature can foster empathy for others. While reading this book in Bhadrapur, I felt for the character in Russia.

16.13°C Kathmandu

16.13°C Kathmandu