Opinion

Social roots of authoritarianism

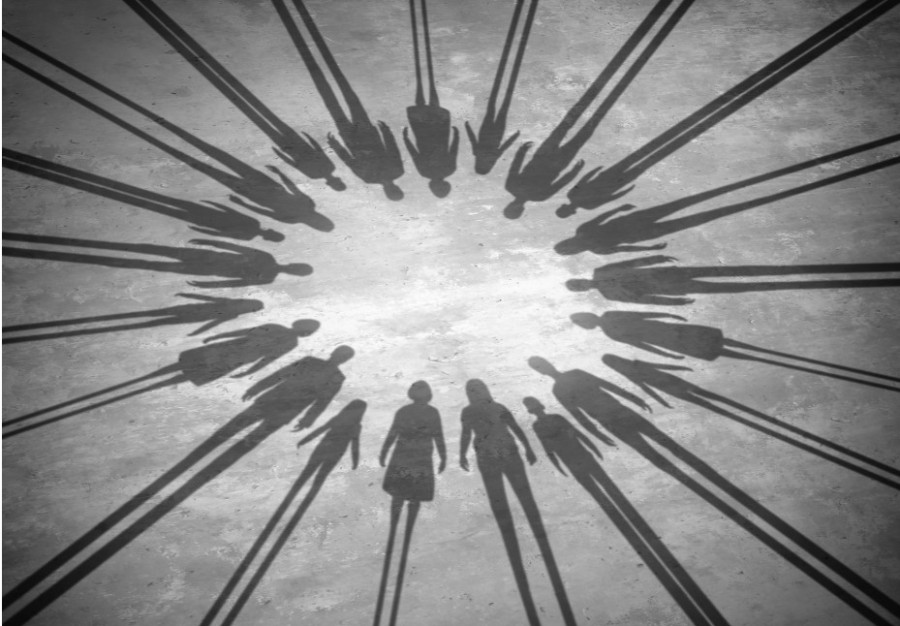

We blame the prime minister’s ‘authoritarian’ tendencies for constricting the space of civil society, but we need to do some introspection.

Ajaya Bhadra Khanal

In the recent months, there are three observations to be made.Civil society and the political opposition is growing weaker, the incidences and magnitude of corruption are increasing and the K P Oli government is tightening political control through authoritarian policies and edicts.

We tend to blame PM Oli’s ‘authoritarian’ tendencies for the series of attempts in recent years to constrict the space of civil society in Nepal. However, blaming him only serves to hide the real source of the problem. The shrinking space of civil society is not just a result of PM Oli’s governance, it is a result of our society itself. The PM is merely piggybacking the social wave.

Therefore, if we are to address the challenges to democracy posed by PM Oli’s government, we must also turn to Nepali society as a whole and how it is being used by hidden political and financial interests.

Social roots of political control

The resurgence of Nepali "nationalism" after 2013 received fuel from narrow-minded ideals intolerant to the idea of multiculturalism. While the first constitutional assembly represented the ideals of multiculturalism and social movements around the rights of marginalised people, the second constitutional assembly, riding on a surge of Nepali nationalism, pushed the society in the opposite direction restricting the space for multiculturalism, rights-based social movements, and federalism.

Currently, we are seeing the next phase of that resurgence: restriction and control of the civil space and human rights movements. Nepali nationalism has been able to disseminate the idea that the ‘civil society,’ understood in its current form, is a bearer of western values intent on weakening the Nepali state and disturbing the harmony of the Nepali society. Some nationalists even go to the extent of claiming that CSOs largely work to promote the strategic interests of western powers, including the promotion of Christianity.

Most people believe that the primary reason for Nepal's underdevelopment is political instability coupled with social disorder and indiscipline. The country’s political, sector as well as the media, appear chaotic and indisciplined; there are significant malpractices in the civil society and media sectors that need to be corrected. The desire for stability and political control, therefore, appears rational.

However, the society's nationalist ideals and the desire for political control is helping political and financial interests oftentimes largely hidden and unaccountable to the people. At the moment, they set the national political agenda and undercut popular representation. Civil society remains the only viable opposition to these groups that pose a significant threat to our national and public interests.

In addition, there is a stark gap between Nepal's international commitments (to values of human rights, democracy and good governance) and political realities at home. In facilitating the restriction of the space for the civil society organisations, the Nepali society is also helping widen that gap.

However, the most significant source of corruption and disorder in the civil society and media are the political and financial interest groups themselves.

Workings of the interest groups

According to former UN Special Rapporteur, Maina Kiai, in many instances, the civil society performs an oppositional role to the market and the state while promoting common public interests; the civil society's ability to operate is being restricted for this very reason.

In Nepal's case, the market has been distorted by corruption and crony capitalism. In its crudest form, our market is represented by financial interests, which in turn are represented by a small number of brokers, businesspersons, holders of public office and political leaders.

The government appears to be trying to maintain political control by selectively targeting individuals and building cases against them. Politicians have raised this issue during party meetings and cite the fear of retaliation as one of the reasons why few have dared to raise critical voices in the parliament and in public against the government.

Financial information units, formed in many countries including Nepal as part of Financial Action Task Force’s global initiative against money laundering and terror financing have been used as a double-edged sword. While the unit’s purported objective is to counter money-laundering, it has been used in some countries to control foreign funding of civil society organisations.

Despite significant differences among top-level political leaders belonging to different political parties, the factor that continues to create cohesion among them is illicit finance. Politicians claiming to have inside information say that the agents of corruption, in many instances, are playing a significant role to maintain cohesive relations among top political leaders.

The media, similarly, is a key battleground between the state, the people, and the business interests. Distortions in the media are largely a result of the operations of the vested political and financial interest groups.

For example, one trend is the use of media bias and defamation by a section of ‘journalists’ to extort money from businesses, politicians and government institutions that have a soft underbelly, usually because the latter engage in corruption, malpractices, and abuse of authority.

The other trend is for actors to use media to attack and weaken their competitors or actors when they threaten their political, personal, or financial interests. Sometimes what looks like good investigative journalism is actually motivated and facilitated by dark, sinister interest groups.

Given these dynamics, hidden political and financial interests tend to gain the most from the triangular conflict between the state, the civil society, and the resurgent Nepali nationalism.

The political parties and politicians are part of civil society. However, in order to become part of the state, they have to carefully balance their relations with the people versus their relations with the market.

The society’s responsibility is not just to elect leaders to represent their interest, it is also to hold them accountable. But first, society must become aware of how its desire for social order and political control is facilitating and aiding corrupt interest groups.

Khanal can be reached at [email protected]

22.23°C Kathmandu

22.23°C Kathmandu.jpg)