Opinion

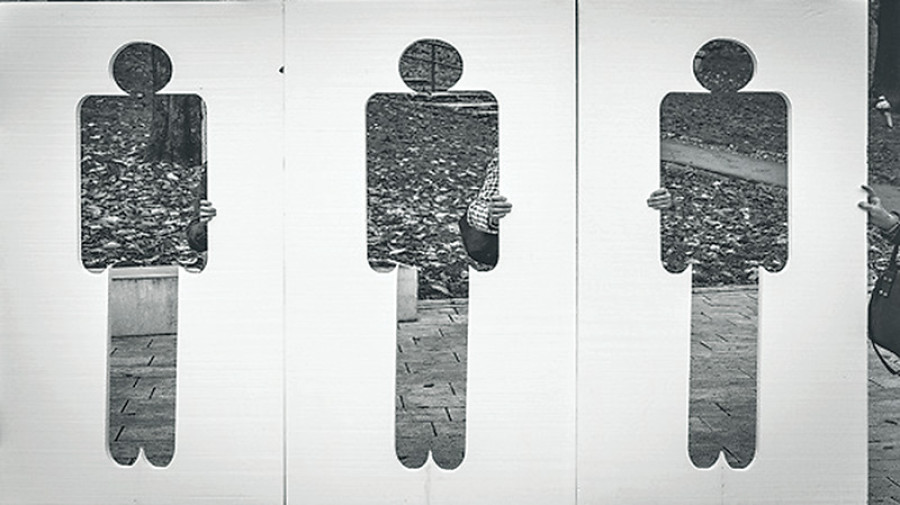

The disappeared

Every year, as part of the global movement against enforced disappearances, we commemorate the International Day Against Enforced Disappearance.

Ram Kumar Bhandari

Every year, as part of the global movement against enforced disappearances, we commemorate the International Day Against Enforced Disappearance. On this day, we present a platform where the voices of families affected by enforced disappearances can be raised, we express solidarity with the struggle for justice worldwide and remember our beloved family members who were forcibly taken away from their communities and never seen again.

From 1996 to 2006, Nepal endured a civil war in which hundreds of citizens were forcibly disappeared by state forces and the Maoist rebels. It is a human tragedy to live in a state of ambiguity. Thousands of families miss their relatives, and as the search for those who are missing continues, these families remember them every day.

The survivors’ questions

Nepal’s Comprehensive Peace Agreement (CPA) in 2006 declared searching for the disappeared and addressing the needs of their surviving families as a national political commitment, but it is one that the state has failed to fulfil.

Families are left with a series of unending questions: Why has the state failed to address the families’ demands for truth and justice? Can Nepal address the structural violence committed during the war, especially considering that it was systematically planned by state security forces? Why does the state repeatedly fail to deliver justice and punish the perpetrators? Can Nepal commit to not repeating the cycle of disappearance? Why has the government failed to criminalise enforced disappearance as a crime against humanity? Why is the state unable to answer the question of whether they are dead or alive?

My own question is: Why did innocent people disappear without the state providing the truth about what happened to them? The answer to this question, official acknowledgement of the incident, and a commitment to address the livelihood and security needs of conflict survivors are important for all. These questions are raised by the families of the disappeared every day and must be addressed immediately.

Commission for the disappeared

Can the Commission of Investigation on Enforced Disappeared Persons (CIEDP) answer these questions? Without providing adequate answers, the commission will be deemed a failure; it must be held accountable for the abuse of resources that has resulted in a loss of human life and has made thousands of families wait in vain for so long.

The CIEDP seems to lack the political will to search for truth and justice, and instead appears as a weak mechanism that only serves political interests. Additionally, the commission’s delayed response and unwillingness to act for truth and justice has shown a lack of competence, independence, and willingness to solve cases. The CIEDP has been both slow and passive in undertaking processes—not only due to a lack of resources or because of the limitation of its mandate, but also because of the government’s tendency to hide the truth to protect culprits.

Numerous institutions and the government are protecting culprits by claiming that none of the commissions can investigate them or question their past. Prime Minister Sher Bahadur Deuba defends the security forces and openly said in a recent programme that, “Security institutions will not be investigated and punished for the cause of their involvement during the war.” There is a long list of alleged perpetrators who hold political appointments in the security forces; these alleged perpetrators are using state resources to sabotage the voices of the disappeared families. The surviving families do not feel secure in this current situation of state denial. So far, the CIEDP has documented violations, but without a disappearance law in place, it cannot conduct proper investigations and present cases for prosecution. The influence of alleged perpetrators and the power they have over the commission presents a serious threat to the protection of available evidence and files of the disappeared.

For over two and a half years, the commission has neglected to push for fair, victim-centred investigations. This is not surprising, considering that most of the commissioners were appointed by political parties as their loyal agents.

A staff at the CIEDP Nisedh Sharma (name changed) says, “The commissioners are close allies of various political parties, they are politically guided and loyal to their political agenda.” He went on to say, “the security forces have installed agents as government staff; under these circumstances, it is very difficult for the commission to mobilise these staff to conduct fair investigations and to keep cases confidential.” These facts show that neither the commissioners nor the government staff have an interest in maintaining the commission’s credibility.

The process of taking statements from the families of the disappeared has proven to be biased and weak, as reflected in the preliminary interview with families. If the desired end is a political reconciliation, these statements will fall extremely short. Ramesh BK (name changed) said, “The investigator came and interviewed me for less than 10 minutes; I was highly disappointed when they asked me, without detailed discussion, whether or not I could pardon the perpetrators. It seems as though the process is fully preparing the ground for a fake reconciliation.”

The commissions do not have a serious plan to address families’ security, livelihood and memorialisation concerns. A frontline family activist Bhagiram Chaudhary says, “The process is politically controlled, now I have little hope that we will get justice within the perpetrators’ state; this is not only a political betrayal but also a big insult to the families’ demand for truth.”

The government and concerned agencies must listen to the families’ demand for truth and must respect their right to know. The painful past of enforced disappearances must be resolved with a guarantee that nobody will face such a situation in the future, or be deprived of the right to life.

9.51°C Kathmandu

9.51°C Kathmandu