Theater

A whirlwind of emotions

Mandala Theatre’s ongoing play ‘Hiu Bhanda Chiso’ transports the viewer to a night of existential frenzy at an isolated village in the far west.

Urza Acharya

It’s a picturesque village somewhere in the far west. After a two-hour drive and half an hour walk, a doctor, Siddant, and his subordinate Gopi—a temp worker at a nearby health post—arrive at the latter’s village at twilight. The houses are all lit up, albeit dimly, forming a quaint little cluster. However, these houses are all empty. Except for one. That’s where Gopi, his wife Navrati and their three-year-old son live.

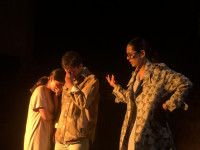

This is the opening scene of Mandala Theatre’s ongoing play ‘Hiu Bhanda Chiso’ (Colder Than Snow). Directed by Som Nath Khanal and translated by Namrata KC, the stage hosts just three characters: Bholaraj Sapkota as the doctor, Renu Nath Yogi as the wife Navarati and Govinda Sunar as Gopi.

An adaptation of actor/writer Saurabh Shukla’s Hindi language play ‘Barff,’ the play takes place over the span of a single night, morphing elements of social realism with psychological thriller. The end result is a whirlwind of escalations that’ll leave you on the edge of your seat.

Siddant, an easy-going urbanite, decides to visit Gopi’s house as he learns that his child is unwell. We soon realise that he’s going there despite Gopi’s multiple attempts to dissuade him—arguing that his wife tends to exaggerate things and that his son is doing fine.

There’s something unsaid in these attempts. However, Siddhant, blinded by his attempt to do good, is unaware of the subtle worry behind the sweetness in Gopi’s voice.

The play is a masterclass in foreshadowing. Gopi’s constant ‘Let’s go backs’ hint that something sinister is at play, but they never spill out more than they should. So, as they walk towards the village through a thick jungle, you don’t know what’s coming.

As we arrive at Gopi’s little house, dadyaas or mastos (clan deities of the Khas-Arya communities) are hung around the cottage—their large faces with sunken cheeks and uncanny eyes adding to the mystery.

Siddant soon realises that nothing is like what it seems. However, it is too late to go back. A series of events unfold—involving a broken Chinese doll, the soul of a girl that hung herself at a nearby tree, and a car key hidden by Navrati, all accumulating into a truly terrifying ‘Get Out-esque’ situation.

The play reminded me of films by Ari Aster (‘Hereditary,’ ‘Midsommar’ and ‘Beau is Afraid’), as it managed to create a deep sense of discomfort and impending doom—without the use of overt jumpscares or cliche psychological horror tropes.

As the play progresses, the couple’s warm hospitality transforms into animosity, sometimes even resulting in violence. However, it is important to note that Gopi and Navrati aren’t your usual antagonists. They aren’t one-dimensionally evil, rather, they are products of isolation, dejection and, in the case of Navrati, a serious case of psychosis.

As a method of survival, Siddant is forced to abandon his sense of reality and truth. Sapkota achieves this with his dry wit—making the audience laugh and worry simultaneously.

The performances by all three actors on stage are what makes the play compelling. Sunar, as Gopi, strikes the perfect balance between wanting to help Siddant while also reinforcing the harmful delusions of his wife. Yogi thrives in the duality of the dangerous yet delicate Navarati, giving a performance that lingers long after the play ends.

Though the play is bound to a small house in an abandoned village, its implications are universal—mainly in how it asks us to re-think our notions of truth and beliefs. When Siddant rebukes Gopi for feeding into Navarati’s warped sense of reality, he calmly argues that truth is manufactured. “Just look at how people have so much faith in a stone or a lifeless deity,” he says.

Moreover, the play also hints at how—throughout history—trust (be it in love or superstition) has always triumphed over rationality. It forces us to acknowledge the uncomfortable fact that we often reject rational, sensical arguments to accommodate and justify our actions, ideologies and hopes.

‘Hiu Bhanda Chiso’ brings something new to the table. It moves beyond the didactic, ‘social message’ stories that the theatre community is comfortable with—braving into the realms of neo-noir.

Here’s to hoping that more plays make that jump.

Hiu Bhanda Chiso

Duration: 1 hour 30 minutes

Where: Mandala Theatre, Thapagaun, Kathmandu

When: Till July 30

Time: 5:45 pm (closed on Mondays, with an extra 2:30 pm show on Saturdays)

Entry: Rs500, Rs300 for students (limited seats)

15.87°C Kathmandu

15.87°C Kathmandu