Profiles

New face of old money: Why Akshay Golyan believes he’s earned his inheritance

At 37, the new chairman of Golyan Group is restructuring one of Nepal’s oldest conglomerates while defending the legitimacy of private enterprise itself.

Aarya Chand

When Akshay Golyan speaks about leadership, he is precise. “When you start treating a company like your child,” he said, “your logic becomes personal rather than business.”

It’s a telling philosophy for understanding the 37-year-old chairman and managing director of the Golyan Group, one of Nepal’s most diversified industrial conglomerates. In December 2025, Golyan formally assumed leadership from his father, Pawan Golyan, taking the helm of operations that span manufacturing, exports, energy, and agriculture across more than sixty countries, employing nearly ten thousand people.

His ascent comes at a moment when Nepal’s private sector faces deep structural constraints and rising public scrutiny. Golyan occupies a position that is not merely corporate, but representative – a visible figure in debates about capital, legitimacy, and national economic direction.

Weight of a Name

The Golyan name is well known in Nepal’s business circles – sometimes spoken with admiration, sometimes with suspicion, often invoked as shorthand for inherited influence in a country uneasy with visible wealth.

When asked about criticism that he was born with a silver spoon, Golyan’s response is direct: “I am aware of this criticism but I am not burdened by it.”

He attributes much of it to narrative rather than action. “A lot of that criticism comes from incorrect journalism,” he told The Kathmandu Post in a recent interview that spanned nearly two hours. “Controversy is consumed more eagerly than context.”

While he was reluctant to speak on contentious issues at the beginning, like the recent Reliance Spinning Mills IPO controversy, in which lawmakers and investors alleged the company inflated earnings and withheld liabilities, he opened up in a follow up conversation. ‘‘If there is legitimate concern, then of course it’s my duty to speak up,’’ he said.

Following the IPO, multiple regulatory bodies sought explanations. ‘‘We went to all the departments. We gave our clarifications, our answers, even in written form. At the time, we spoke very clearly,’’ he said. What followed, he argued, was noise rather than context. ‘‘You can’t respond every time there is noise. Otherwise, you validate it,’’ he said.

Golyan asserted he was confident in the company’s books, its stakeholders, and the process itself. And he rejected the idea that the criticism reflected broader public doubt. Multiple legal challenges ended up with rulings in the company’s favour. For Golyan, the ultimate test was the market response: the IPO was oversubscribed more than thirty times at Rs820.20 per share. ‘‘That was the public answer,’’ he said. ‘‘And investors spoke with their money.’’

Golyan’s larger concern extends beyond personal reputation. When private businesses are persistently portrayed as illegitimate, he said, “investment slows, ambition recedes, and some choose to leave the country.’’ Over time, he added, the consequence is not personal, but national.

For a company contributing nearly 10 percent to the country’s total exports, Golyan sees those structural anxieties as inseparable from operational ones. Energy infrastructure, he said, remains the most critical constraint. “Nepal has massive hydropower potential, but infrastructure and transmission remain bottlenecks,” he said.

For Golyan, the bottleneck is not abstract. The Golyan Group is now one of Nepal’s most aggressive private investors in renewable energy, building a portfolio that stretches across hydropower and solar projects through a number of energy subsidiaries.

Along the Balephi River in Sindupalchowk, the group operates a 36-megawatt Balephi Hydropower and is developing the 46-megawatt Upper Balephi plant; in the eastern hills, KBNR Isuwa’s 97.2-megawatt project anchors its expansion, while Mizu Energy’s 54-megawatt plant in Dolakha and Apollo Energy’s 89.7-megawatt project extend its footprint across river basins and transmission corridors.

Taken together, the group’s named hydropower assets exceed 320 megawatts in capacity. In total, Golyan forecasts a 14-project renewable pipeline that he hopes will push the group past 700 megawatts of combined hydro and solar by 2030, turning the infrastructure bottleneck he criticises into the central arena of his own long-term wager.

That wager has also sharpened his policy view. At present, only the Nepal Electricity Authority can sell electricity. Golyan believes in allowing independent producers to sell directly to manufacturers at negotiated rates. “Costs would fall, demand would rise, and production as well as GDP would grow,” he said.

He also seemed irked by policy inconsistencies, which he believes exacerbate the problem. “The government always claims it wants to encourage production,” he said. “Budget statements routinely emphasise it.” The missing factor, for Golyan, is alignment between policy intent and regulatory execution.

Earned, Not Given

Golyan’s counter to inherited privilege lies not in rhetoric but in his apprenticeship. When he joined the family business in 2017, he didn’t begin in an executive role.

“I used to stay in the factory for months,” he said, learning how yarn was produced from raw material to finished output. “I like to learn everything from scratch. If I don’t even know how our products are made, then how will I manage it?”

He spent time in smaller Indian towns, gathering information through conversation rather than reports. Turkey became one of the first export markets he handled himself, visiting five or six times a year. Pricing, logistics, and supply decisions were learned on-site.

“It’s not that it was just handed over to me, saying: okay, here it is, now you take care of it. I’ve gone through it step by step,” Golyan said. He describes authority less as a position than as a function – something exercised in response to process, not inherited symbolically.

This gradual accumulation of responsibility contrasts sharply with his original plans. After completing his MBA from Esade in Barcelona, Golyan had planned to stay on in Spain. He had verbally accepted a job offer in luxury hospitality with a local Spanish company that specialised in curated travel for ultra-high-net-worth clients. ‘‘It was curated hospitality — very high-end,” he said, describing that role. “It designed everything for clients from logistics and flights to hotels and restaurants reservations.’’

At the time, his interests lay in sports, hospitality, event planning – not the family business. But his family wanted him back, and in 2017, he returned to Kathmandu.

Structure and Discipline

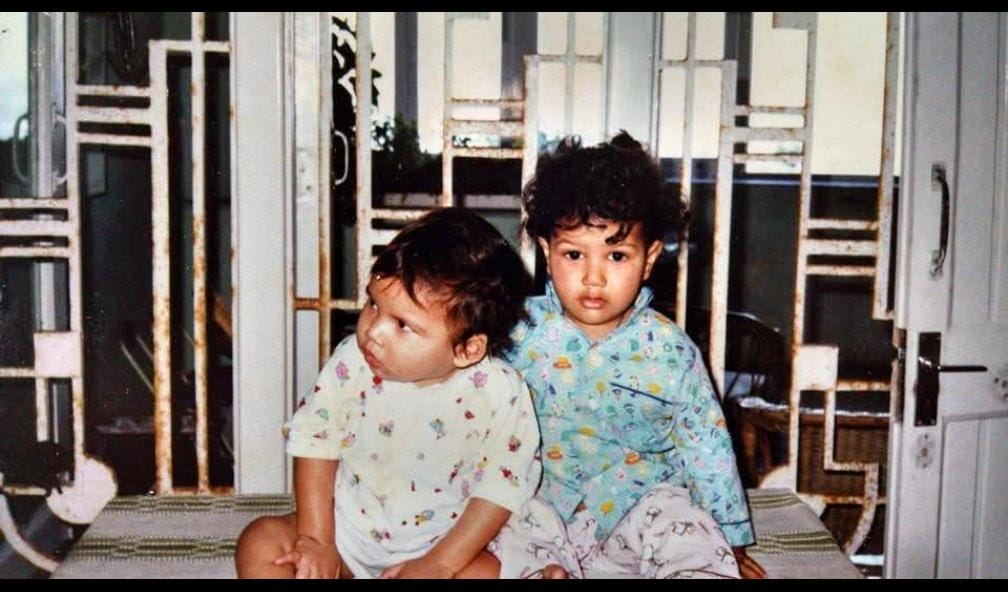

Golyan said the foundations of his approach were laid long before he entered the business. Pocket money was fixed growing up – Rs500 per week. “There was no space for demanding more,” he said. “All I knew was I’ll be getting a certain amount and I have to manage my life around it.”

He remembers this not as limitation but a lesson in financial discipline before he understood finance.

When he attended Lincoln School, he said his pocket money ran short. He worked as a facility coordinator at a museum, paid by the hour. “That was my first actual job,” he said.

University life in Spain and The UAE shaped him structurally. His classes ran five days a week. Group assignments stretched late into the night. “I used to sleep approximately four or five hours,” he said. What he remembers most is dependency. “It taught me that you’re always part of a team. You either succeed as a team or fail as a team.”

For Golyan, individual performance in academic projects mattered only insofar as it affected the group. “If you don’t do your part, then the entire team fails. So you had to succeed individually but as a group,” he said. He carried that idea later into his management style.

The Architecture of a Person

When Golyan arrived at his namesake company headquarters in Baneshwar on a recent afternoon, the office was quiet. His tenth-floor office opens onto a wide balcony with sweeping views over Kathmandu, rooftops punctuated by distant hills and temples. His assistant placed a black coffee on the table. Despite emerging from Kathmandu’s chaotic traffic, he seemed at ease – a calm that felt practiced.

Golyan keeps details of his personal life deliberately private. What he makes visible is structure: one engagement flows immediately into the next, meetings stacked back-to-back. He wakes around 6:30 am, begins the day with strong black coffee, and goes to the gym four times a week.

“What powers my day is my own motivation,” he said. Motivation, to him, is not an abstraction but something practical, like time. “No food works if you don’t have inner motivation or drive to do anything.”

Time, in fact, is something Golyan does not believe is scarce. “Time is an illusion,” he said. “You have to make time and it will always be available.” The challenge to him is not shortage but inefficiency.

Among academic interests, history held Golyan’s attention most. Ancient Egyptian history fascinated him – pharaohs, empires, state formation – and the Egyptian relics placed on his office table were evidence of that. Later, he got into European empires, Mongol expansion, and Nepali unification. “I've read a lot of the history of Prithvi Narayan Shah,” he said.

But history, for Golyan, is not just nostalgia. “It’s very interesting how different incidences, small incidences, shape the course of where we are today.” He applies the same lens to business. “[This] company also carries sixty years of history.”

When asked whether leadership can feel lonely, Golyan pauses. “It’s not lonely. But your ability to connect with a lot of people goes down,” he said.

Businesses require decisions that may be correct but emotionally difficult: negotiations, pivots, closures, exits. Golyan offers the example of startups he has shut down, not as confessions but as lessons learned from failure. One of those projects was called “Bottle Ups” which he launched shortly after returning to Kathmandu. It was a reservation app designed to let users book tables and receive discounts at cafes and restaurants. They piloted it through bakery cafes before expanding to restaurants across Kathmandu. ‘‘The idea was simple,’’ he said. ‘‘You reserve a table, you get a benefit.’’ But it never reached scale. After twelve months, they shut it down.

For Golyan, the point isn’t failure, but clarity: “You have to know when it’s time,” he said. “Shutting something down isn’t always a loss. Sometimes it’s the right decision.’’

Responsibility, in Golyan’s view, is infrastructural. It is built into systems, not announced. At Reliance Spinning Mills, a daycare center operates inside the factory, providing childcare, nursing spaces, play areas for children of families. It has existed for three years. “People work nine to ten hours a day. Especially single mothers, they require these facilities,” he said.

Across his business, similar initiatives exist, from donating ambulances to organising sports events for local communities. The latest example is a program Golyan Group announced in October last year, making a commitment to provide full scholarships for 32 children of martyrs who lost their lives during the Gen Z protests in September. Golyan said he treats these initiatives as extensions of operational presence, not branding exercises.

Looking Forward

Even though he’s been on the job for a month, he has a definition for what success looks like for him before retirement. “This organisation should work independent of me,” he said. He imagines stepping back one day, but not disappearing.

If he can find time, he hopes to build projects related to wildlife conservation. “I want to develop wildlife tourism that benefits both people and animals,” he said. “Imagine resorts where visitors can stay close to tigers inside the national parks.”

For him, Nepal's parks are among the country’s most underutilized resources. “In Africa, national parks are central to tourism,” he said. “We have some of the most beautiful parks in the world, yet we haven’t leveraged them or created a strong global brand.”

Infrastructure is crucial to realizing this vision. “Our international airport has limited capacity, parking is constrained, and flights are insufficient. We need better roads, possibly trains, and facilities near Kathmandu that can handle more visitors,” he said.

Does he ever see himself in politics? “It is inevitable for business leaders,” he said. “However, I don’t want to be involved in politics.”

16.13°C Kathmandu

16.13°C Kathmandu