Opinion

Take cognizance

The Belt and Road Initiative seems to be replicating China’s unfair policy towards weaker nations

Ayush Manandhar

In July 2017, the then Nepali Prime Minister Pushpa Kamal Dahal awarded a 2.5-billion-dollar project to China’s Gezhouba group to build the Budhi-Gandaki hydroelectric project. Just four months later, the deal was rescinded by a new pro-India Sher Bahadur Deuba government citing that was made in a “thoughtless manner” without adequate transparency. Upon being elected in February of this year, current Prime Minister KP Oli expressed ambitions to “revive” the deal once again. However, the Ministry of Energy announced in May that it would abide by the Deuba government’s decision and would prepare a new tender for the project.

This deal, when originally signed, was earmarked under China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), one that has been regarded as the country’s most ambitious economic and diplomatic strategy. The BRI is primarily an infrastructure project that would not only reroute global trade for the benefit of China but would also expand their cultural and strategic priorities. The initiative— which consists of infrastructures such as railroads, pipelines, ports, refineries, and power plants among many others—now spans across Asia, Europe, the Middle East, and Latin America. According to the American Enterprise Institute, it has already totaled an investment of approximately 340 billion dollars since its announcement in 2013 and is anticipated to reach a trillion dollars within the next six or seven years. By investing primarily in developing nations, China hopes to amplify its economic and soft power capacity and thus establish future market and strategic opportunities.

However, China cannot attain these opportunities alone. They would require strong partnerships among nations, starting from their home continent, Asia. The rise of Asia should, thus, be parallel to the rise of China for these opportunities to materialise. Currently, while China’s ambitions, at a glance, may seem both grand and bona fide for the benefit of Asia, a careful study of these projects suggest otherwise. It is, therefore, vital to recognise that the significance of the BRI will highly depend on not just China’s actions in promoting fundamental development practices and initiatives for developing nations in the continent, but in conducting non-discriminatory agreements with their less powerful

Asian neighbours. Likewise, it will also be important for the rest of Asia to carefully conduct business with China and look to derive long-term mutually favourable strategies. As of now, none of these seem to be happening.

Fulfilling the fundamentals

China’s ignorance towards the urgency for fundamental development practices and initiatives is explicit in their Budhi-Gandaki hydropower agreement with Nepal, which showcases two glaring weaknesses. The first of which is an issue of stability, as Asia constitutes some of the world’s most politically volatile nations. The Nepali example of a new government annulling a deal made by a pro-Beijing predecessor showcases how the BRI will be dependent on the political stability of host nations. While Nepal’s present government seems to be stable for the next few years, it does not remove the reality for other developing nations in Asia.

The same example showcases an issue of transparency. A lack of transparency is not just a concern for the many Asian nations within the BRI, but also for China itself. Many Asian countries have an absence of political accountability while they are still in the nascent phases of building proper governance. Additionally, even China is critiqued for settling agreements without utilising proper measures of transparency both in the past and with deals currently made under the BRI. Thus, it will be vital for China to prioritise improved governance and stability within host nations, while also conducting transparency within their agreements as a part of the initiative’s overall development agenda.

Deception and debt

Problems within the BRI do not stop here. Historically, Chinese policies have proven to be unfair towards weaker Asian nations, and now the BRI seems to replicate this. Many, for instance, critique the Chinese railway project in Laos. While some even question its necessity, the project is also a financial burden, costing twice the host nation’s annual budget. Additionally, contrary to projections that the project would create 100,000 jobs, people in Laos have had minimal benefits, as most construction work has been assigned to Chinese companies. In addition, the BRI has dramatically increased the host nation’s debt to GDP ratio, putting them under high financial risk.

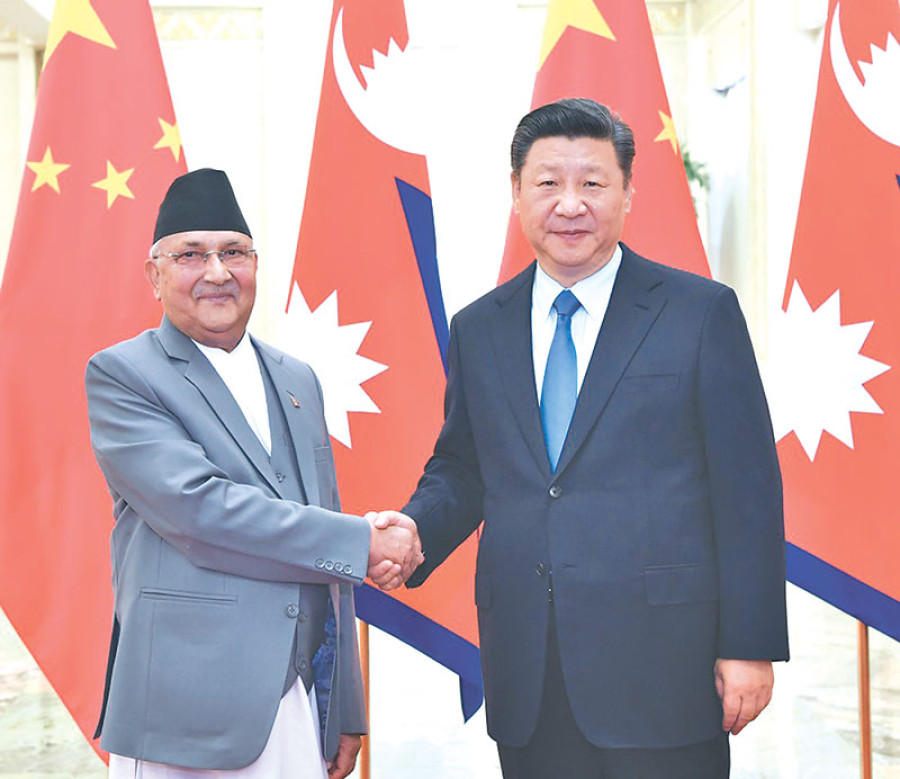

In light of this, Prime Minister Oli made his first trip to China last month and agreed to intensify cooperation for the BRI. He also signed 14 agreements, including one to develop a cross-border railway project between Kerung and Kathmandu. While the finer details are yet to be announced, when speaking about the BRI prior to leaving for China, his Foreign Minister Pradeep Gyawali was quoted saying, “he does not believe debt trap is always bad as some people suggest.”

While Minister Gyawali may seem to minimise the burden of large debts, the realities are different. In addition to Laos, many other Asian countries are currently struggling with large debts held by China. Last December, for instance, Sri Lanka handed China a strategic port in Hambantota for a 99-year lease upon grappling to pay a debt of more than a billion dollars. Additionally, the US-based think-tank, The Center for Global Development, has listed Laos, Pakistan, Mongolia, Tajikistan, Kyrgyzstan, and the Maldives, to be at a very high risk of financial vulnerability due to the rise in debt through the BRI.

These examples underline skepticisms of China’s assurance of a “win-win” collaboration. It will, therefore, be vital for countries in Asia to tread carefully as they negotiate deals under the BRI. Additionally, China needs to develop themselves as a cooperative force allowing opportunities for developing economies in Asia to garner the long-term benefits of the BRI. Without these vital alterations, a vibrant continent such as Asia will be bound towards incessant instability that will prevent China from embracing their global ambitions while also disabling the many developing economies within Asia to garner their full potential.

Manandhar is pursuing Masters in Public Policy at Georgetown University, Washington DC

9.15°C Kathmandu

9.15°C Kathmandu