Health

Covid-19: The year of living dangerously

One year since Nepal reported its first case, government response has been dismal. Vaccines are likely to be available sooner or later, but the path to inoculate all is not clear.

Arjun Poudel

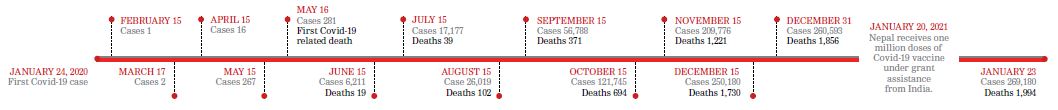

It has been a year since the first case of coronavirus was detected in the country.

The World Health Organisation’s collaborating center in Hong Kong had on January 23, 2020 confirmed that a 31-year-old Nepali student, who returned from Wuhan, China, where the virus is believed to have originated, was infected with the new virus. The government made the news public on January 24.

A year later, the novel coronavirus, named SARS—CoV-2, that causes Covid-19, has infected 269,180 and killed 1,994 people in the country.

Worldwide, the virus has infected 98,889,601 and killed 2,19,416 people.

As the virus was novel, very little was known about the infection then, and like all countries and territories throughout the world, authorities in Nepal too had to deal with the viral infection by learning from others’ and its own experiences.

“This is neither the first pandemic nor will it be the last,” Dr Baburam Marasini, former director at the Epidemiology and Disease Control Division, told the Post. “What we learned from our own and from others’ experiences and what we did to contain the infections should be reviewed.”

The world witnessed at least half a dozen pandemics in the last two decades—SARS, MERS, avian flu (H5N1), Swine flu (H1N1), Zica, Ebola and SARS-CoV-2.

After the second case was detected in Kathmandu in March, the government enforced a nationwide lockdown, which lasted four months.

Soon authorities rolled out rapid diagnostic tests without completing validation despite warnings from experts that it was the wrong test to conduct.

While international flights were suspended from March 21, migrant workers returned from India in hundreds of thousands, but authorities failed to manage the quarantine facilities, which turned them into virus breeding grounds.

Efforts on contact tracing, one of the major components of curbing the spread of infections, were never concerted enough from the beginning and no attempts were made to improve it.

Contact tracing apps were developed but never used.

Even Prime Minister KP Sharma Oli downplayed the risk declaring in Parliament that sneezing and drinking turmeric water would cure the infection and Nepalis had strong immunity and therefore should not be unduly worried.

Authorities kept extending lockdown and other restrictions, but did not care to enforce mandatory wearing of masks, social distancing and other aspects of risk communication.

Later the government gave up all preventive measures including testing and contact tracing. While testing and treatment had been free up to October, the Cabinet decided to provide free tests and treatment only to frontline health workers and the underprivileged even as the daily infections continued to rise reaching a high of 5,743 cases on October 21.

The Supreme Court overturned the decision but only symptomatic people were provided free testing thereafter and contact tracing was brought to a complete halt.

The number of daily polymerase chain reaction tests declined but pressure in the intensive care unit and ventilators increased.

Science was defied and suggestions of experts were ignored by the government leadership. Doctors say that ad-hoc decisions were responsible for the rampant spread of the virus.

The numbers of daily infections now hover below 500 a day but risks are not over yet despite vaccines having arrived in the country, doctors say.

“The ongoing pandemic proved that the burden of disease can be upended any time,” Dr Sher Bahadur Pun, chief of the Clinical Research Unit at the Sukraraj Tropical and Infectious Disease Hospital, told the Post. “Pandemic not only affects people’s health but also the country’s economy, social development, education and others.”

Any outbreak that happens in any corner of the globe has a chance to come to Nepal and the world is interconnected and such an outbreak can happen within the country itself, doctors say.

“But we still keep learning,” said Marasini. “If another new pandemic starts, we again start learning but do not use the experience.”

Incidentally, exactly a year after its first Covid-19 case, the country is preparing to roll out vaccination against the coronavirus after receiving a million doses from India under grant assistance.

The government plans to inoculate 400,000 people that include health workers and other frontline workers with the vaccines that arrived on Thursday. Each person requires two doses within 28 days.

As for the rest, the government is seeking funds to procure additional vaccines and had earlier estimated that it would need Rs48 billion to inoculate eligible Nepalis. Authorities are planning to inoculate 72 percent of the total population, as the remaining 28 percent people are children under 14 on whom the approved vaccines have yet to be trialled. The COVAX programme of the World Health Organisation will provide vaccines for 20 percent of the population as a grant. The first lot for 3 percent population will be delivered by April, according to officials.

With the whole world lining up to be immunised against Covid-19 and the government’s lacklustre efforts, it is not certain how long it will take for all Nepalis to get the jab.

“It is not possible to buy all required doses at once, so the government has made a priority list,” Dr Shyam Raj Upreti, coordinator of the Covid-19 vaccine advisory committee, told the Post. “We are preparing to roll out vaccines for 3 percent of the population and 20 percent will be provided to us by WHO. This will cover all the people of the high-risk group.”

But preparations are not yet in place to inoculate those who are on the priority list.

As the Covishield vaccine developed by the University of Oxford and pharmaceutical giant AstraZeneca has not been trialled on people under 18 years old, the government has to buy vaccines for around 45 percent of the population if it has to use only the Covishield vaccine.

This is the preferred choice for Nepal as the existing vaccine storage and transportation infrastructure support it.

The Ministry of Health and Population has put people above 55 years on the first priority list, as the death rate in this age category is very high. Officials say this group accounts for 12.13 percent of the population.

“If we could purchase at one go sufficient vaccines to immunise those in the first priority, we will immunise them at the same time. If not, we will break down that age group,” Upreti added. “If we could give vaccines as per the priority list, death rate, as well as impacts of the coronavirus, will be lessened significantly.”

While some experts are of the view that private companies should be permitted to import vaccines, others say the poor and those at high risk will be deprived if private companies are allowed to bring in vaccines.

“I want to repeat again that the government is committed to inoculating all of the eligible citizens with the vaccine against the coronavirus,” Dr Bhagwan Koirala, chairman of Nepal Medical Council, the national regulatory body of medical doctors, told the Post. “We should let it fulfil its commitment and responsibility towards the people first.”

Only if the government fails to bring the vaccines should private companies be allowed to procure them, according to Koirala.

A source at the Health Ministry said officials have agreed to discuss whether or not private companies should be allowed to import vaccines after 20 percent of the population is covered.

Dr Prabhat Adhikari, an infectious disease and critical care expert, said the government should keep the option of procuring vaccines produced by other companies as Covishield cannot be given to people under 18, pregnant women and those having immunity compromised.

“Vaccines of Pfizer, Moderna or of Chinese companies, which are protein-based, can be given to those people,” Adhikari told the Post. “The United Kingdom itself produced the vaccine but has also been importing vaccines of nine different companies.”

Adhikari said that the government should not be afraid of the private sector, as it can enforce priority rules in private companies as well and fix the price.

“After all, we have to immunise people with vaccines against the coronavirus and break the transmission chain,” he added. “The price of vaccines may be lower like in the polymerase chain reaction tests if we let the private sectors import.”

The Health Ministry used to say that each PCR test cost over Rs10,000 in the initial phase but gradually the prices went down to Rs5,400, Rs4,400, Rs2,400 and Rs2,000.

Despite the good news of the vaccine arriving in the country, experts have a warning.

Many things about it are still unknown.

“We do not know how long the vaccine will provide us with the immunity and if the same vaccine works when the virus keeps mutating,” said Pun, who is also a virologist.

Precaution is still the best way to keep the coronavirus at bay.

“We should keep following safety measures. Use of masks, social distancing and hand washing should be used continuously to minimise the risk of coronavirus and other infections,” Pun said.

13.12°C Kathmandu

13.12°C Kathmandu