Editorial

At the talks table

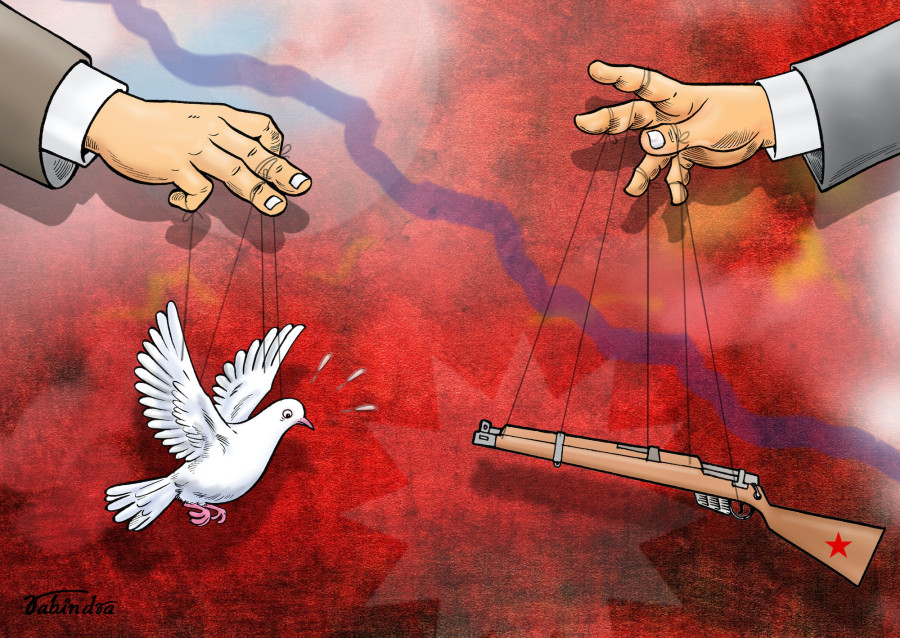

There is no alternative to dialogue for lasting peace.

History repeats itself, first as a tragedy, then as a farce, said Karl Marx, the reigning deity of many of Nepali communists and leftists. In 2002, cadres of the Communist Party of Nepal (Maoists), which organised the 10-year insurgency, brutally murdered Muktinath Adhikari, a Lamjung-based high school headmaster, for refusing to kowtow to the party's demands. Eighteen years later, on Tuesday, cadres of the Communist Party of Nepal, a splinter of the erstwhile Maoists, killed Rajendra Kumar Shrestha, 54, the principal of Saraswati Basic School in Ramite of Miklajung Rural Municipality in Morang district. The Mechi-Koshi bureau of the outfit had abducted Shrestha from his home before killing him purportedly 'for working as an informant' for the police.

The latest killing is a chilling reminder that the Maoist insurgency did not get over in its entirety as the political parties and the state did not care much to tie up its loose ends. The insurgency left over 13,000 dead, 1,333 disappeared and hundreds of thousands displaced in the decade beginning in 1996. The country has remained considerable peaceful after the Maoists came to mainstream politics following the People's Movement II in 2006, and the signing of the Comprehensive Peace Agreement in 2007. However, the political upheavals in the years that followed left enough space for hardliners in the Maoist party, including the likes of Netra Bikram Chand as well as various other outfits, to see violence as the gateway to political power. Now, the Chand-led organisation has begun to kill people it considers 'counter-revolutionary' after organising a series of bomb blasts, extortions and other kinds of violence across the country. It looks like we are back to square one with regard to political violence.

As if it were an unprecedented occurrence, the Nepal Police has sent a fresh directive to its units across the country to increase security vigilance, claiming that there is a risk of an increase in criminal activities, although it has claimed the directive is for forceful implementation of the security plans that are already in place. The Maoist insurgency and the peace process that followed have enough lessons for us on the successful management of political violence, the pre-eminent one being that no amount of brute power is able to contain insurgent voice and violence. There is no doubt that the state must use its resources to stop incidents of violence and extortion in the short run. But in the long run, there is no other place where the state and the insurgents must meet other than at the dialogue table.

All major parties in the country today have a history of violence, and what they have all learnt—or should learn if they haven't already—is that violence is hardly the catalyst for political change. If the ex-Maoist combatants who came to power riding on the insurgency believe they can contain violence by any means sans dialogue, they are in for a rude shock. If the Chand-led violent campaign is not nipped in the bud, it is more likely than not to grow bigger sooner than later. The political parties and the ruling government must sit together immediately to chart out a comprehensive plan to bring the Chand-led outfit to the dialogue table immediately and help restore peace. They can't repeat the mistake they committed in 1996 when they ignored the possibility of dialogue, only to see an endless series of violence in the years that followed.

23.88°C Kathmandu

23.88°C Kathmandu