Columns

Transitional justice has failed former child soldiers

They deserve special support from the government to genuinely complete Nepal’s peace process.

Kul Chandra Gautam

Today marks the 15th anniversary of the signing of the Comprehensive Peace Accord (CPA) that ended the decade-long Maoist insurgency. Dubbed as “People’s War” by the Maoists, the insurgency was undoubtedly the most violent and destructive period in modern Nepali history. Its negotiated end brought a sigh of relief on the war-weary people of Nepal. Some of the provisions contained in the CPA also brought hope that it would herald a new era of lasting peace and prosperity in a more inclusive, equitable and democratic Nepal.

The decade following the peace accord was a testing period for the Nepali people’s patience as our politicians squandered precious time and resources squabbling about power-sharing, perks and privileges. Instead of focusing on a massive post-conflict reconstruction and development, for which there was strong international solidarity and support, our politicos spent billions of rupees from the national treasury for the upkeep of 19,000 Maoist combatants in temporary cantonments. More billions were spent, and two expensive elections held to draft a new constitution. Even then, it literally took the massive earthquake of 2015 to shake up the political leaders to complete the document.

In my 2015 book Lost in Transition: Rebuilding Nepal from the Maoist Mayhem and Mega Earthquake, I recount the trials and tribulations of this long and painful transition, including some of the mistakes and miscalculations by the international community. On the positive side, compared to many other prolonged post-conflict situations around the world, Nepal’s peace process was largely home-made and Nepali-led, and it managed to avoid any relapse into further conflicts as has been the case in many other countries. Some aspects of Nepal’s peace process were truly unique and exemplary. For example, where the large United Nations Mission to Nepal (UNMIN) floundered in its last years and months, it took the home-grown ingenuity of a retired Nepal Army general with UN peacekeeping experience, Gen Balananda Sharma, to pacify the restive Maoist combatants who had started rebelling against the avarice of their own commanders in cantonments.

As we celebrate the 15th anniversary of the CPA, it is worth recalling that there are three unfinished aspects of the peace process that our political leaders are loath to address, but which simply cannot be wished away and will come back to haunt us if we don’t address them more forthrightly. These are (a) Transitional justice, (b) The plight of former child soldiers, and (c) Reform of our security sector.

Transitional justice

An estimated 17,000 people were killed during the Maoist insurgency, and tens of thousands were forcibly displaced and disappeared. The vast majority of them were innocent civilians, including teachers, petty businessmen, peasant farmers and women and children. Atrocities were committed by both sides in the conflict. But not a single person, either from the Nepal Army or the Maoists, has been brought to justice. The UN Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights has documented 9,000 cases of heinous crimes and gross human rights violations, including dozens of “emblematic cases” involving war crimes, crimes against humanity and violation of international humanitarian law. Instead of being punished, some of these “emblematic” perpetrators have been promoted to high positions in the Nepal Army, the Maoist party and the Nepal government. Some perpetrators supposedly under police arrest warrants walk freely and attend high profile events right under the nose of senior police officers and top political leaders.

Part of the problem is that under the heavy-handed pressure of the Maoists and the Nepal Army, the government enacted deeply flawed laws governing the functioning of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission as well as the Commission of Investigation on Enforced Disappeared Persons. Nepal’s own Supreme Court has ruled that these laws are inconsistent with the spirit of the CPA and non-compliant with international norms. The UN and other respected national and international human rights organisations have denounced these laws. The Truth and Reconciliation Commission and the Commission of Investigation on Enforced Disappeared Persons formed under these flawed legal provisions have lacked credibility and have proven to be toothless and ineffective. While the Nepal government and senior political party leaders claim that there will be no general amnesty and impunity against gross human rights violations, their actions and inaction belie their words. No wonder the victims of conflict are getting organised and agitating for genuine justice.

On the eve of the 15th anniversary of the CPA, a group of ambassadors and the UN Resident Coordinator are believed to be trying to broker a deal whereby the prime minister and top leaders of the major political parties have been urged to sign a declaration of “non-recurrence” of such atrocities in the future, and to address the demands of the conflict victims. It is to be hoped that these diplomats are not misled as some of their predecessors, and that they and the Nepali stakeholders will seek a more binding commitment for action with measurable milestones and deadlines, and not be satisfied by our leaders’ lofty declarations.

Justice for ex-child soldiers

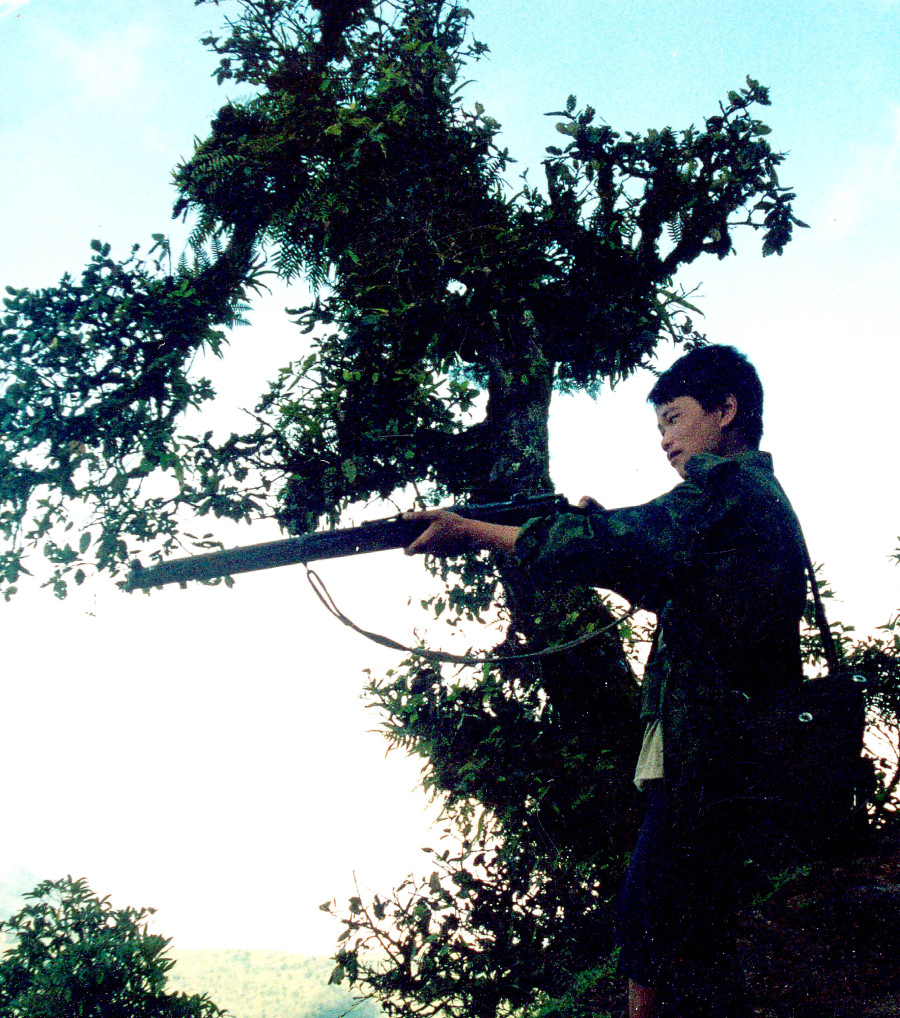

Child soldiers were widely used during the decade-long Maoist insurgency. They were recruited mostly from schools under false pretences of joining the Maoist militia for cultural performances, often without the consent or knowledge of their parents. Once lured into the Maoist cultural troupes, they were brainwashed into believing that “the bourgeois education” they were getting was useless, and that if they joined the “People’s Liberation Army” and contributed to the victory of the Maoist revolution, they would get better education and have a better life and career.

Many children lost their lives during combat and many were disabled. But throughout the period of insurgency, the Maoist leadership officially denied that they ever recruited children in their militia. This was an issue of special concern to me as a senior official of the United Nations Children's Fund (UNICEF). When I inquired with the Maoist leadership, including their ideologue Baburam Bhattarai, we were assured that the Maoists fully complied with the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child, and that it was not their policy to recruit children. However, the UN received reliable reports from national and international non-governmental organisations that the Maoists did recruit and deploy a fairly large number of child soldiers. Indeed, for over 10 years the Maoists were on the UN blacklist of non-state actors illegally using child soldiers as reported to the Security Council by the Secretary-General’s Special Representative on Children and Armed Conflict.

After the end of the conflict, UNMIN carried out physical verification of the Maoist combatants. It found out that there were over 3,000 combatants who were either still under the age of 18 or were recruited when they were minors. Consistent with the CPA, the Agreement on Monitoring of the Management of Arms and Armies and international norms, these youngsters were to be quickly released and reunited with their families and provided appropriate support. Although these ex-child soldiers were “ineligible” for integration into the Nepal Army or other security services, the Maoists kept them in cantonments falsely promising them that they too would be integrated into the Nepal Army like all other combatants. Instead of honouring their commitment to respect UNMIN’s findings, the Maoists cynically incited the ex-child soldiers to protest their classification, insinuating that arrogant and insensitive foreigners deliberately insulted these proud and patriotic youngsters using the Nepali word ayogya or “incompetent”.

When UNICEF and other UN agencies with support from various donors prepared and offered a package of vocational training, educational and job opportunities for the ex-child soldiers, including a special package for girls who had been married and had small children, Maoist leaders dismissed and disparaged the package and persuaded the ex-child soldiers to reject the UN offer as less than “honourable”. The Maoist leadership then tried to negotiate alternative packages that would keep the “disqualified” combatants in certain group formations in which the party would continue to keep them under its patronage and surveillance. When that effort failed, and pressure from the international community mounted, the Maoist leadership essentially abandoned the ex-child soldiers and let them leave the cantonments with just a pittance in their pocket. Understandably, the ex-child soldiers left the cantonments feeling unhappy, frustrated and mistreated.

Having missed out on basic education and any employable vocational training, these ex-child soldiers lack the skills and support necessary for making a living. Many of them face stigma and non-acceptance back in their communities, and are vulnerable to abuse and exploitation. No wonder, some of the former child soldiers have now organised themselves into a victims’ movement and are demanding justice and reparations. While the Maoists were responsible for misleading them, ruining their childhood and depriving these youngsters of educational opportunity, helping them is now the responsibility of the government and the whole of Nepali society. They deserve some special support from the government, and possibly with some international assistance, to genuinely complete Nepal’s peace process.

13.58°C Kathmandu

13.58°C Kathmandu