Columns

Preserving women’s bodily autonomy

The disruption of family planning services is a profound cost that will be borne by entire countries.

Natalia Kanem

By the age of 24, Maya Bohara had borne four children, and she and her husband decided that their family was large enough. For nine years thereafter, despite living in a poor region of Nepal, she could rely on a local health clinic for injectable contraceptives.

But then came Covid-19, which disrupted medical supply chains and health budgets around the world. By June 2020, Maya’s clinic was out of the contraceptive she had been using; and by February 2021, her fifth child was born. Although the Boharas’ new baby is deeply loved, a vulnerable family has now been put in an even more precarious position.

They are hardly alone. For women around the world, one of the most serious costs of the pandemic—beyond the direct toll on lives and livelihoods—has been the loss of reproductive choice. These are lifetime costs that might be borne even by generations to come.

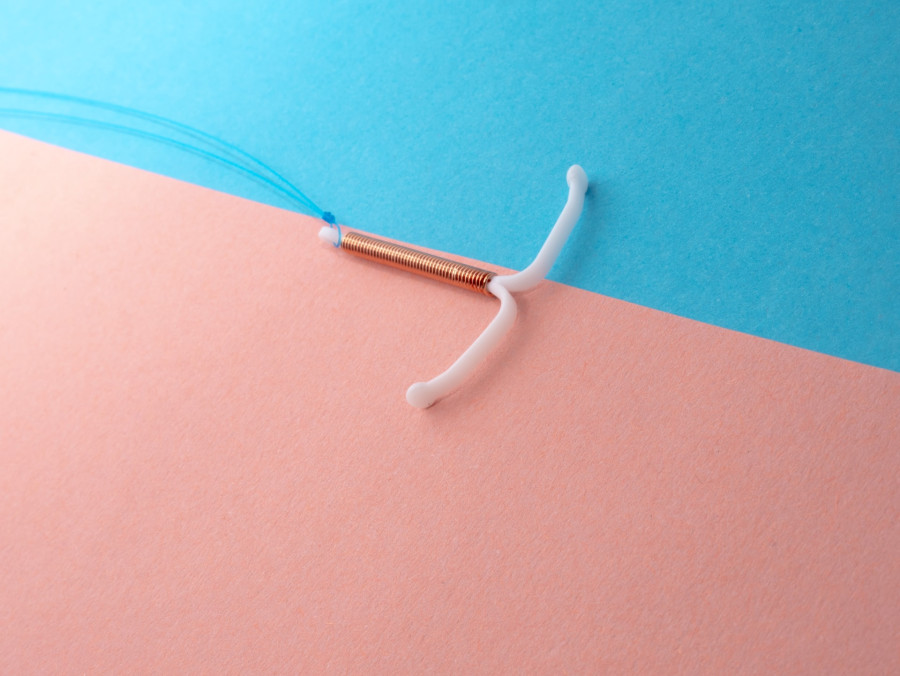

This April, the United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA), the UN sexual and reproductive health agency, published My Body Is My Own, a groundbreaking edition of our annual State of World Population report. In it, we trace the link between sexual and reproductive health and bodily autonomy, a principle that is absolutely fundamental to women’s self-determination and empowerment. Only when women have control over their bodies can they benefit from rights and opportunities in all other areas of their lives, whether that means going to school, caring for their family, starting a business, or leading a country.

By the same token, any loss of bodily autonomy quickly multiplies. According to recent estimates by UNFPA and Avenir Health, an estimated 12 million women in 115 low- and middle-income countries faced disruptions in family-planning services during the first year of the pandemic, leading to around 1.4 million unintended pregnancies. Such outcomes—a cause of increased maternal deaths and unsafe abortions—are one of the starkest manifestations of lost bodily autonomy.

If there is one bright spot in these figures, it is that the most severe disruptions to family planning occurred early in the pandemic and were for the most part short-lived. For its part, UNFPA stepped in to provide contraceptives and other reproductive health supplies to countries in need.

At the same time, many health systems have come up with creative measures to ensure sustained access. In Uganda, the SafeBoda ride-hailing app now delivers contraceptives to users’ doorsteps. In Eswatini, UN agencies launched an initiative to inform tens of thousands of women about family planning services through SMS alerts. In northern Brazil, family planning counselling is conducted through telemedicine, and contraceptives can be delivered by community health agents on bicycles. In rural Nepal, family-planning counsellors travel for hours to provide free services to women in remote quarantine centres, ensuring that their confinement does not lead to gaps in contraceptive use.

Globally, the percentage of countries reporting pandemic-related disruptions to family planning and contraception services has fallen from 66 percent in 2020 to 44 percent in 2021. Concerted efforts by health officials, governments, and donors have greatly mitigated a catastrophe for women. In some cases, solutions were implemented so quickly that women do not even know that their sexual and reproductive health and rights were at risk.

In a way, that is as it should be. The 1994 International Conference on Population and Development established a common agenda for sexual and reproductive health. And at a summit in Nairobi 25 years later, governments, businesses, youth and women’s activists, philanthropies, and others made bold commitments to end family-planning shortfalls, preventable maternal deaths, and gender-based violence and other harmful practices against women and girls.

This international support has enabled UNFPA to operate sexual- and reproductive-health programs in more than 150 countries. Since 2008, medicines and contraceptives delivered through our Supplies Partnership have saved countless lives and prevented almost 90 million unintended pregnancies. Moreover, this work has helped to instil an awareness of sexual and reproductive health as a fundamental human right, which is an important reason why these services were quickly restored after the initial shock of the pandemic.

But we cannot be complacent. These gains are fragile, and funding continues to be threatened by the pandemic’s economic fallout. Many countries have altered their spending and service priorities; some of the UNFPA’s own programs have been affected by major spending cuts in the United Kingdom—one of the organisation’s oldest and strongest partners.

Under these conditions, we must fight even harder to ensure that sexual and reproductive health remains a top priority. Failing that, it is not just individual women who will suffer. Entire countries will experience increased levels of socioeconomic vulnerability and inequality, making it even harder to recover from the current crisis, let alone build resilience against future natural disasters, pandemics, and climate change.

To reduce the risk to sexual and reproductive health, a top priority should be to scale up investments in these services by making them an integral part of national recovery plans. In countries with limited fiscal space, the international community must lend more support through debt relief so that governments do not have to divert funds from health care to pay off creditors.

A second priority is to ensure that services actually reach all women and girls. This requires overcoming complex barriers related to location, education, age, and other factors that can impede access to care. Services must be made available across the lifespan, from adolescence to old age, covering everything from comprehensive sexuality education to routine cancer screenings.

Covid-19 has taken so much from so many. We cannot allow it to take even more by denying women sexual and reproductive health. All women have the right to live in safety, with easy access to the medicines that they need to make empowered, autonomous decisions about their own bodies and their lives.

—Project Syndicate

9.89°C Kathmandu

9.89°C Kathmandu