Columns

Failing our migrant workers

One would have expected the present government to be more attuned to the challenges faced by workers in destination countries.

Deepak Thapa

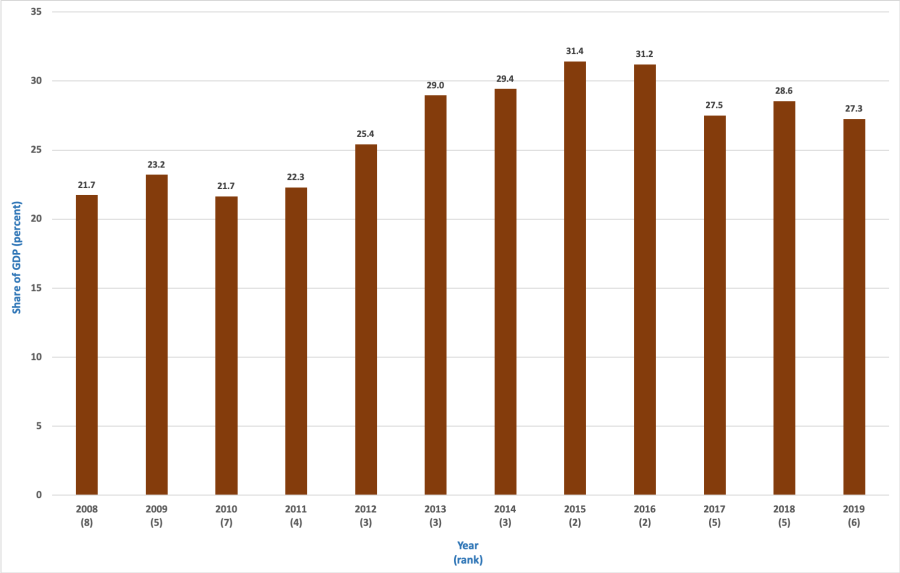

Hitting the top 10 of anything is generally an event to be celebrated, especially when the unit in question is one’s country. But even when nationalism is on overdrive here in Nepal, there is one distinction that scarcely any Nepali can or should feel proud of: our clear and overt reliance on our compatriots working abroad to keep our economy afloat. For, since the year 2008, Nepal has consistently featured among the top 10 countries in terms of the contribution of remittances to the national GDP. This, of course, does not refer to the absolute volume of remittances, since the biggest recipients over the same time period are our neighbours, India and China, in that order, but is still an alarming indicator.

Although never able to hog the dubious number one spot, we did reach number two twice and number three thrice in the past 12 years. The share of remittances approached a third of our national earnings two years in a row, 2015 and 2016, and has not dipped below 25 percent for the past eight years. That is the debt we owe the hundreds of thousands of Nepalis labouring in extremely adverse circumstances in some of the most inhospitable climes in the world.

And, how have we been expressing our gratitude? First and foremost, by allowing their exploitation to continue unchecked—and this begins at home. One example is the ‘free-visa-free-ticket’ policy introduced to some acclaim five years ago. The syndicate representing recruitment agencies need not have bothered at all with the agitation they began in protest immediately since, as with everything else, it would all boil down to implementation. Nearly four years after it was announced, the Supreme Court had to order the government to enforce its own policy—as usual, to no avail. I know, since a neighbour of mine went to Malaysia in late February after paying Rs270,000 instead of the mandated maximum service charge of Rs10,000. This is a young man from Kathmandu, a veteran of numerous stints abroad, fully cognisant of government regulations on recruitment, and yet having no choice but to shell out a rather astronomical amount. Luckily, as a security guard, he was not affected by the pandemic and has since been able to repay part of the loans taken out by his family to finance his migration. But the idea that he will be working for months to come doing just that is enough to wrack one’s heart.

The Covid-19 pandemic and the havoc it has wrought on labour markets, mainly in the Gulf, and tens of thousands of Nepalis trying to come back, offered the government yet another opportunity to demonstrate what it thinks of our working heroes. First came months of non-response to the desperate calls for help reported daily in the media. Then, instead of organising massive airlifts on an emergency scale to bring the workers back home, the government appeared eager to favour profiteers who were out to fleece migrant workers of their meagre savings—if they had any. It took activism and a Supreme Court order for the government to begin the process of utilising the Foreign Employment Welfare Fund, set up through mandatory contributions from the workers themselves, to repatriate those stranded abroad. The government has since prepared guidelines on how the Fund is to be used towards that end, but at the time of writing, it had been more than a week and it has not received Cabinet approval.

It is also worrying that the government does not plan to extend any help to those who went abroad without a labour permit. Known as ‘irregular migration’, this is a practice that mainly women resort to because of the highly irrational bans the government introduces periodically on female migration. Thus a substantial proportion of the migrant population, and one that is among the most vulnerable, is likely to be denied any government assistance, all because of a technicality imposed by the state itself. Regardless of what the law says, at a time of crisis, all Nepalis below a certain income threshold should be able to look forward to a helping hand from their government, not least because they, too, have contributed to all those remittances flowing in hard currency over the years.

It has never been the preference of our nationalist-communist government to send Nepalis for foreign employment, as the previous labour minister stated in no uncertain terms. As self-proclaimed champions of workers, one would have expected the present government to be somewhat more attuned to the challenges faced by workers in destination countries though. Yet, there has been no perceptible difference in how the official machinery has functioned to support all those Nepalis who feel they have no choice but to seek employment in foreign lands in order to survive.

The plight of migrant Nepalis stranded at the Nepal-India border was there for all to see. But, conditions were hardly different in other places. Take the kind of services Nepalis can expect from our embassies, and I offer the example of Qatar. According to one authoritative source, Nepalis comprise 16 percent of the total Qatari population, which means there are around 304,000 Nepalis in Qatar. Servicing them, our embassy in Doha has a total of just 10 people, and that includes the ambassador. There are only two labour attachés allocated to Qatar and one position has remained vacant over these crucial months. Compare that with the Filipinos, whereby they make up 11 percent of Qatar’s population but their embassy has a staff base of 44. Meaning, there is one embassy personnel for every 4,750 Filipino workers in Qatar compared to one for every 30,400 Nepalis (that, too, contingent on all 10 positions being filled). Granted that the Philippines earns three times as much through remittances than Nepal but that hardly justifies leaving our workers more or less to fend on their own. At a time when layoffs without compensation or flight tickets back home are becoming increasingly the norm, it is the embassy that should be able to weigh in on behalf of the workers but the shortage of hands makes it practically impossible for any kind of meaningful intervention.

Another indicator of how the government sees the labour migration sector as only a cash cow is in the government’s budgetary allocations. According to the details provided in the Red Books over the past three years, the line ministry in charge of foreign employment, the Ministry of Labour, Employment and Social Security (MoLESS), received 0.32 percent of the national budget in 2018-19, a figure that went up a fraction to 0.45 percent in 2019-20, and inched up further to 0.57 in 2020-21. The funds set aside for MoLESS is meant not only for its units dealing directly with foreign employment—the Department of Foreign Employment and the Foreign Employment Board—but also the Vocational and Skill Development Training Academy, the Department of Labour and Occupational Safety, and the Social Security Fund. This mismatch between the contribution of foreign employment to our national income and the priority accorded to the sector by successive governments perhaps explains the dire straits migrant workers find themselves in all the time—at home and abroad, pandemic or no pandemic.

Further proof of how our government perceives the labour migration industry came just a few days ago with the appointment to the Foreign Employment Board of two highly controversial individuals involved in the foreign employment business. One of them declined the offer on health grounds, and we can hope it was because he developed a conscience. Which is much more than can be said of the minister who appointed him.

23.88°C Kathmandu

23.88°C Kathmandu