Culture & Lifestyle

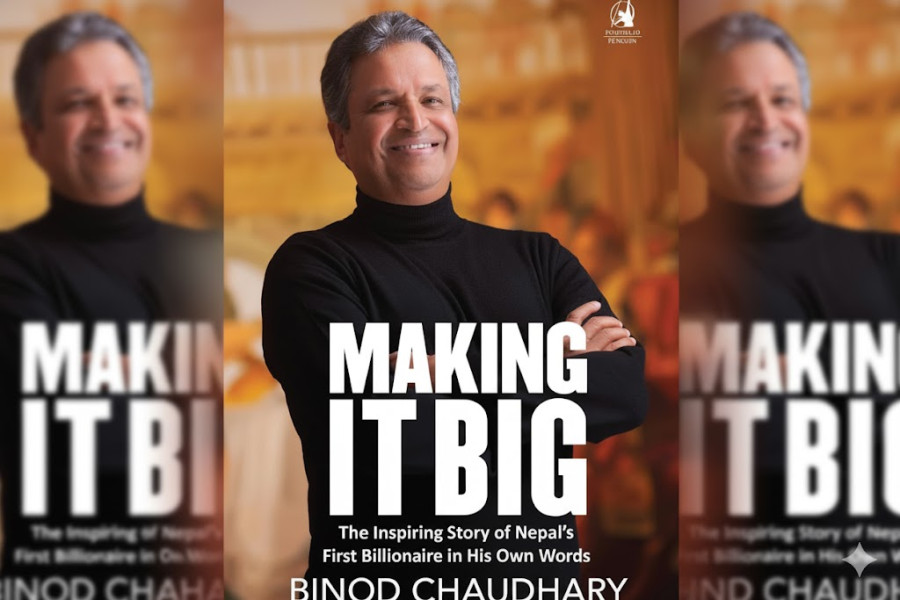

A billionaire’s story that inspires but doesn’t quite soar

Binod Chaudhary’s autobiography, ‘Making It Big’, chronicles his rise from a textile shop in Indrachowk to global business fame—but the writing struggles to match the scale of his success.

Michael Siddhi

In just three generations, from beginning as a small textile merchant in Indrachowk to becoming Nepal’s only Forbes-listed billionaire, Binod Chaudhary’s story is a masterclass in entrepreneurial grit—a journey shaped by business acumen, political hurdles, and regulatory challenges. Chaudhary’s life story is inspirational, from his humble upbringing in the streets of Kathmandu to sharing a communal toilet on his first trip to Mumbai to forging partnerships with the Tatas.

The book unfolds in March 2010, when Chaudhary and his wife experience a terrifying earthquake in Santiago, Chile. From there, it follows a broadly chronological path—from his early childhood to his eventual recognition as Nepal’s first Forbes-listed billionaire. Narrated in the first person, the book begins with Chaudhary’s grandfather migrating to Nepal, invited by the Rana rulers to establish a trading business. Curiously, his grandfather is never named and is simply called “Grandfather”.

By the time Chaudhary was born on April 14, 1955, his father, Lunakaran Das Chaudhary, had already opened a shop on Juddha Sadak. The narrative then shifts to family anecdotes, his passion for cars and films, the death of his mother, and how his father’s illness thrust him prematurely into the world of business. At this stage, the story risks becoming monotonous until it pivots to the creation of Wai Wai noodles, the rise of the CG conglomerate, and Chaudhary’s encounters with politics and world leaders such as Narendra Modi, Bangladesh’s Hussain Muhammad Ershad and Sri Lankan statesmen.

The chapters on Chaudhary’s professional battles, his engagement in FNCCI, and the birth of an MNC are amongst the most engaging chapters. Particularly compelling are the creation of a foreign business by navigating Nepal’s restrictive regulations, the acquisition of NABIL Bank, clashes over acquiring Butwal Power Company and the Modi Khola project, and the controversy surrounding his blacklisting by the credit bureau.

Chaudhary’s career, which began with selling sarees, is recounted with a candour that reflects his humility. It’s a story of unmatched aspiration, struggles, triumphs, culminating in billionaire status. Yet, despite such a powerful plot, the book falls short. The limitation lies not in the plot but in the writing style, which often lacks literary flair and struggles to sustain reader engagement. The book largely recounts Chaudhary’s life events, relying more on factual narrations than literary finesse that could have given the stories greater vividness.

People generally expect autobiographies to inspire and reflect, not to be a sequence of facts. With sharper editing, the narrative could have been more evocative and inspirational, leaving images that linger long after the final page.

The conclusion, where Chaudhary reflects on his life mantras, feels clichéd and somewhat fails to inspire at the level one expects from a billionaire’s memoir. The book, however, cleverly mirrors its beginning and end: it opens with the earthquake in Chile and closes with the devastating earthquake in Nepal on April 25, 2015. Chaudhary uses this symmetry to underscore the transitory nature of life, and his reflections on happiness offer a rare glimpse into his mindset. This circular structure gives the book a sense of completeness and leaves readers with a thoughtful note to carry home.

First published in Nepali as ‘Atmakatha’ in 2013, the English version, ‘Making it Big’ was later released by Penguin for the South Asian market. The autobiography of Nepal’s first Forbes-listed billionaire is bound to attract Nepali audience, eager to trace the journey of a man who defied the limitations of geography. Unfortunately, the book feels less like an autobiography and more like a journal. A compelling plot is never enough on its own; it is also shaped by narrative style, language, expression, and the creative use of literary devices.

Consider Chaudhary’s declaration: “I have faced hurdles created by the system of politicians and bureaucrats. I will continue to fight the system… even if I fall down, I will pick myself up and forge ahead.” While earnest, such statements veer towards familiar platitudes, missing the refinement that could make them memorable. Similarly, occasional attempts at figurative language—such as describing eyes “red like tomatoes”—feel unimaginative.

Chaudhary’s insights, though often thoughtful, are presented in a matter-of-fact tone that undercuts their potential impact. For instance, his remark, “Everyone in the RNAC board meeting came to eat chicken cutlet,” may be true, but as written, it feels redundant. With better narrative craft, such moments could have been humorous, satirical, or evocative. For Nepali readers, the book can hold interest through familiar characters, events, and settings evoking nostalgia. But the international audiences may find it unrelatable and uncontextual.

The book also suffers from spelling errors and technical lapses, leaving readers to wonder why a stronger editor wasn’t engaged. For instance, it is mentioned that his mother passed away on 9 May 2000, yet an article he supposedly wrote titled ‘A mourner’s letter to the Prime Minister’ is dated 17 May 1999—an impossible chronology. When describing a meeting with Prime Minister Surya Bahadur Thapa, it is written, “What you like us to do, Mr Prime Minister?”. A more accurate rendering would be: “What would you like us to do, Mr Prime Minister?”

Likewise, a well-known Nepali business house, Sipradi, is misspelled as ‘Spripadi’, and his New York hotel partner Sushil Mohinani, is mistakenly referred to as ‘Sushi’ Mohinani. The absence of precise dating also weakens the narrative. An autobiography is expected to anchor events clearly in time, but the book frequently relies on vague timelines such as “Around nine years ago ……..”. which leaves readers unable to place events in context. Even the design details feel overlooked: the ornamental break, a dingbat of chopsticks holding noodles—likely reflecting Chaudhary’s Wai Wai brand is poorly printed and barely recognisable.

The book feels longer than necessary, weighed down by anecdotes that often feel non-essential. For instance, the account of Sri Sri Ravi Shankar and Sai Baba’s supposed powers neither enhances the intellectual depth of Chaudhary’s life story nor are they compellingly written. The memoir does not shy away from glorifying Chaudhary, which is understandable. However, it is harder to overlook the lack of literary flair and craft. Ultimately, as Samuel Johnson observed, “the only end of writing is to enable the readers better to enjoy life or better to endure it”.

Chaudhary’s journey unquestionably embodies resilience and ambition, but the book’s prose does not always capture that spirit with the depth it deserves. With stronger narrative craft, his extraordinary life story might have done more than inform. It would have truly inspired readers to enjoy or endure their journeys.

Around 2020, while travelling to Delhi, I sat in the same row as Chaudhary on an aeroplane. I found him remarkably down-to-earth, kind, and soft-spoken, showing no hint of arrogance. I wondered then whether this demeanour was genuine or a façade. After reading his autobiography, I am convinced his humility was authentic. Such humbleness can only be natural for someone who rose from modest beginnings and self-taught the art of wealth. Probably his book falls short of this extraordinary life, but my admiration for Binod Chaudhary remains undiminished.

8.75°C Kathmandu

8.75°C Kathmandu