Politics

How a photo has come to symbolise long wait for justice

Muktinath Adhikari, a teacher and a member of Amnesty International Nepal, was killed in Lamjung 18 years ago by the Maoists.

Post Report

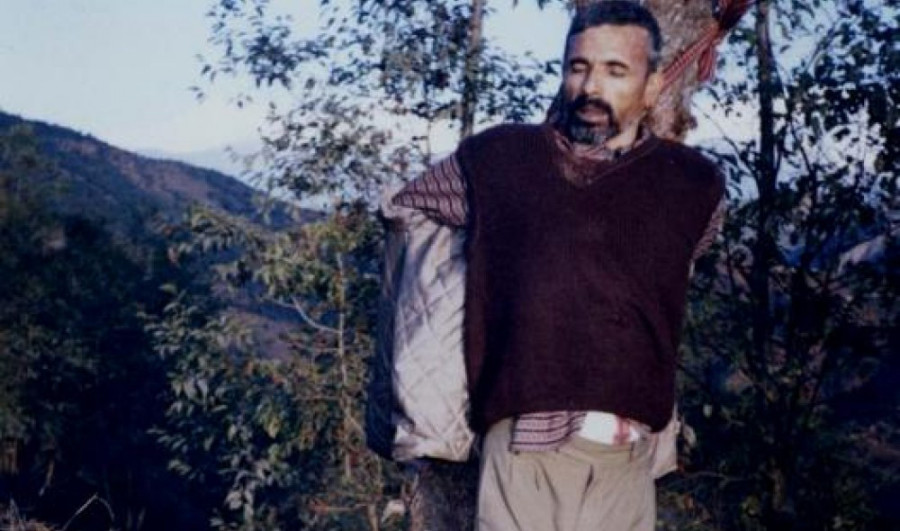

On Friday, a stream of people started sharing a horrifying photo from nearly two decades ago: the lifeless body of a middle-aged man tied to a tree.

The man was Muktinath Adhikari, the headmaster of Parini Sanskrit School in Lamjung and then coordinator of Group 79, Lamjung of Amnesty International Nepal. On January 16, 2002, he was in the middle of teaching a ninth-grade science class when a group of Maoist combatants came to take him away. Despite protests from his students, the Maoists did not relent, according to Suman Adhikari, Muktinath’s eldest son.

The Maoists had demanded a share of every teacher’s salary to fund their insurgency—a practice that Muktinath had opposed, according to Suman.

Muktinath’s legs were tied with a rope and he was dragged half-an-hour uphill. He was then tied to a tree with his own muffler, stabbed repeatedly in the chest and then shot in the head. His body left hanging by the neck, with a warning to all villagers that the body was not to be moved.

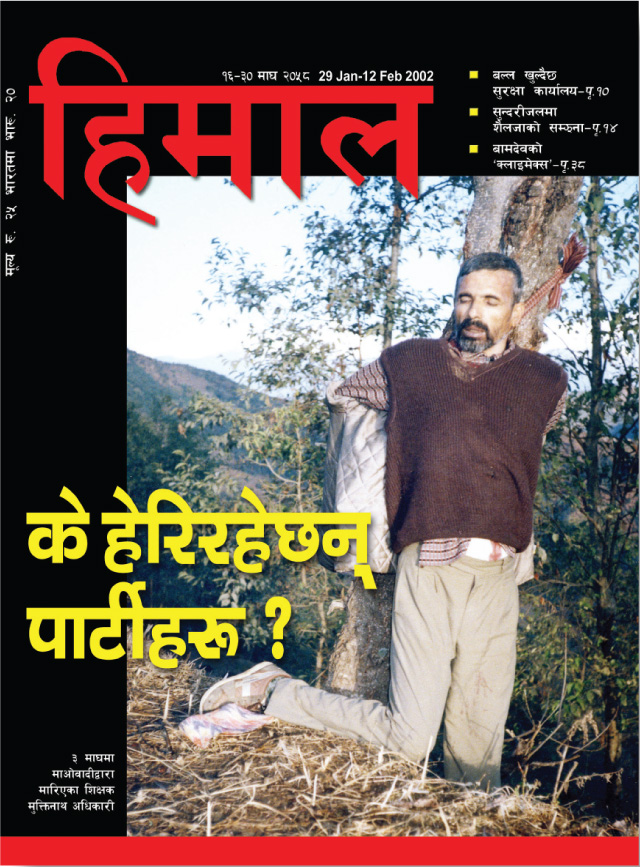

The photo of Muktinath’s body, taken by Ajaya Anuragi and later published on the cover of Himal magazine, came to symbolise the brutality of the 10-year-long insurgency, where non-combatants like Muktinath were caught in the crossfire. And in the years since the conflict ended, the photo has taken on additional meaning, symbolising the long wait for transitional justice for victims and their families.

Read: For victims of Maoist insurgency, no justice and no peace

During the insurgency, there were numerous cases of torture, extrajudicial killing and disappearance, both by the state and the rebel Maoists. When the Comprehensive Peace Agreement was signed between the two sides in 2006, effectively ending the war, both sides had committed to ensuring justice for victims. But 13 years later, families and victims continue to await justice from a process that has been largely co-opted by political interests.

It took nine years for two transitional justice bodies—the Truth and Reconciliation Commission and the Commission to Investigate Enforced Disappearances—to even come into being. Since their formation, the terms of the commissions were extended twice, but they have failed to achieve anything substantial, largely due to a lack of resources and the government’s failure to amend the transitional justice act in line with a 2015 Supreme Court ruling and international obligations.

Read: 12 years on, political leaders dither on transitional justice

The government has, at home and internationally, promised to amend the act, but no steps have been taken to that end so far, much to the disappointment of conflict victims.

The transitional justice process has dragged on for far too long, during which time, victims have been alienated and marginalised. Leaders of the insurgency, both from the Maoists and the state, have instead been making controversial remarks. In one recent speech, Pushpa Kamal Dahal, the supreme leader of the Maoists during the insurgency and current co-chair of the ruling Nepal Communist Party, said that he was ready to take responsibility for 5,000 deaths during the insurgency in which around 17,000 people lost their lives.

In an interview with Baahrakhari, an online news site, on Friday, Suman said that the intention of the state and the major political parties has been to delay the justice process as much as possible so that the families forget the atrocities committed.

17.78°C Kathmandu

17.78°C Kathmandu