National

An electricity project stuck in limbo for 60 years hopes to see the light of day

West Seti, a storage-type hydroelectric project in the Far West, stands as example of Nepal’s sluggish development.

Sangam Prasain, DR Pant & Mohan Shahi

Six decades ago when Jaya Bahadur Saud of Thalakada, Baitadi heard that they were going to “produce electricity” by diverting water from the Seti river to Sornaye through Chama Gadh, he did not believe it at all.

“I actually laughed,” recalled Saud, who recently turned 88. “It felt like an out and out fanciful and unrealistic idea. I even thought how idiotic people can get to think of producing electricity from water.”

But as the survey team arrived, Saud, despite not believing what the members were talking about, was happy because there was a job for him. He was hired as a porter to carry goods for the survey team.

He cannot recall the names or faces of anybody in the survey team. “I faintly remember a Thakuri man from the eastern region mostly talking about electricity,” said Saud, who currently lives in Krishnapur-2 of Kanchanpur.

But there indeed was a project being surveyed. It was just that Saud was unaware of it. The project was the West Seti Hydroelectric Project, a storage-type project.

But the scheme failed to take off. Now, 60 years later, the West Seti Hydroelectric Project is coming back to life.

“If things go as planned, work on the West Seti project could begin from the next fiscal year,” said Sushil Bhatta, chief executive officer of Investment Board Nepal, a government body that deals with potential foreign investors for large projects.

But will it see the light of day? There are many hurdles ranging from investment to geopolitics.

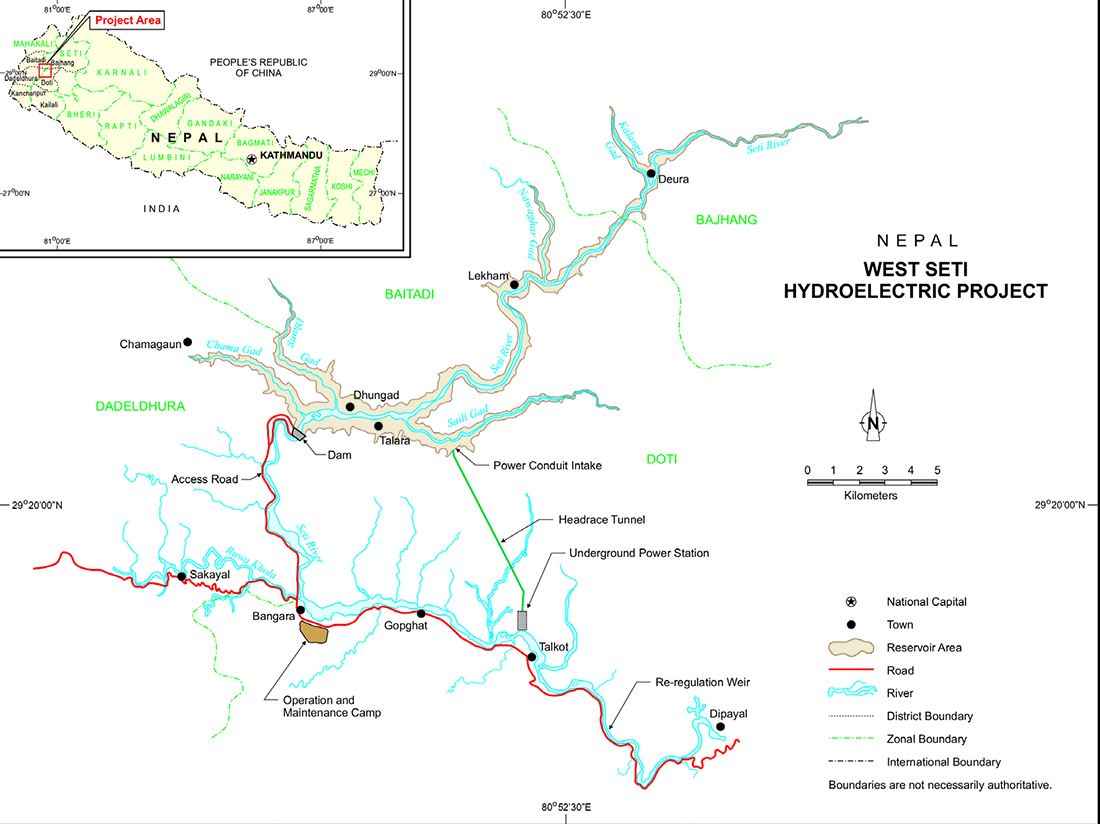

The project is located on the Seti River in the far west of Nepal. The proposed dam site is located 82 kilometres upstream of the confluence of the Seti and Karnali rivers, forming part of the Ganges basin. The project sites are located at elevations ranging from 550 to 920 metres and are spread across six districts.

The main project features are a 195-metre-high concrete faced rock-fill dam, 2,060 hectare reservoir area, 6.7 km headrace tunnel, underground power station, 20.3 km permanent access roads, and 132.5 km of 400 kV double-circuit transmission line to evacuate the power.

All project sites except the reservoir area and transmission line corridor are located in Doti and Dadeldhura districts. The reservoir is located in Baitadi and Bajhang districts, and the transmission line corridor crosses Doti, Dadeldhura, Kailali and Kanchanpur districts.

The reservoir will fill up during the monsoon season (mid-June to late September) and water will be drawn to generate power at peak times each day during the dry season. The reservoir will have a total storage capacity of 1,566 million cubic metres, according to the environment impact assessment.

Soon after Sher Bahadur Deuba became prime minister in July last year, a team of experts including Bhatta, the chief of Investment Board Nepal, visited the proposed dam site situated in Doti in the third week of September last year.

The team members assured locals that the West Seti project “has a lot of potential” and they believe that the project will start this time.

Drones are flying up in the sky at the project site again to collect data, and there is a glimmer of hope among the residents.

In 1981, a 37 megawatt run-of-river scheme was proposed based on preliminary studies conducted in 1980-81.

In 1987, French company Sogreah prepared a pre-feasibility study proposing a 37 megawatt run-of-river scheme without building a dam. Later, the same company revised the capacity to a 380 megawatt storage-type scheme stating that the energy could be optimised without environmental impacts.

“But work did not start,” said Indramani Awasthi, an expert engaged in the social impact studies of West Seti in the past.

West Seti Hydro, a company promoted by Australia’s Snowy Mountain Engineering Corporation, won the survey licence of the project in 1994.

The government issued a construction licence to West Seti Hydro on June 27, 1997.

The project was originally designed as export-oriented with 90 percent of the power intended to be exported to India. However, the project failed to move ahead with its construction whose cost was estimated at Rs120 billion then.

The cash-strapped project got a boost when China National Machinery and Equipment Import and Export Corporation (CMEC) decided to invest in it. CMEC even signed an agreement with the project during the then prime minister Madhav Kumar Nepal’s China visit in 2009.

CMEC President Jia Zhiqiang and West Seti Hydro Director Himalaya Pandey signed a memorandum of understanding in Beijing. The Chinese firm had decided to invest Rs15 billion in the project.

However, CMEC later opted to pull out of the project saying that Nepal lacked an investment-friendly environment. Another important shareholder in the company, the Asian Development Bank, also did not show interest citing lack of public acceptance of the project and absence of good governance.

The project received yet another jolt when the main promoter of the company, Snowy Mountain, stopped sending funds for office operations in August 2010.

The government revoked the licence of West Seti Hydro on July 27, 2011.

Then came China Three Gorges International Corporation, China’s biggest hydropower developer and the operator of the world’s largest hydropower plant at the Three Gorges dam on the Yangtze River.

The project was formally handed over to the Chinese company on August 29, 2012.

In November 2017, state-owned power utility Nepal Electricity Authority signed the final agreement with China Three Gorges International Corporation, a subsidiary of China Three Gorges Corporation, to set up a joint venture to develop the 750-megawatt West Seti Hydropower Project.

In 2018, China Three Gorges Corporation hinted at pulling out of the project saying it was financially unfeasible because of the steep resettlement and rehabilitation costs.

On May 29, the then finance minister Yubaraj Khatiwada, presenting the annual budget, announced plans to build the project by mobilising Nepal’s internal resources. The announcement effectively scrapped a $1.6 billion plan by the Chinese firm.

Awasthi, who has worked as a social scientist and information officer with Snowy Mountain, surmises that West Seti did not start due to the lack of a political will.

“A lack of clear water resources policy, inability to control interference from various angles to not implement the project and lack of will on the part of the leaders have made the project an issue so far,” Awasthi said.

He added that Indian concerns in Mahakali along with Seti is also one major reason for the project not being allowed to start.

“Recent times have been favourable for Prime Minister Deuba,” he said. “There is a strong alliance of five political parties and an environment to take India’s trust with the national situation easing.”

West Seti, whose cost was projected at $1.6 billion a decade ago, has now been remodelled.

In 2019, Investment Board Nepal remodelled the project and presented it at the Nepal Investment Summit 2019.

The West Seti and Seti River (SR-6), a joint storage project, now has a capacity of 1,200 megawatt. It was one of the biggest hydropower projects among eight hydro projects that were showcased at the summit. The project’s estimated cost is $2.02 billion. But investors were not interested.

According to Awasthi, now there is an India-China factor in Nepal’s hydro projects.

The southern neighbour has recently communicated to independent power producers that they must ensure there will be no Chinese components in their hydropower projects if Nepal’s private sector plans to sell electricity in India’s power exchange market.

“The Indian side has been flatly telling us that they won’t buy electricity from projects with Chinese investment and even projects built by Chinese contractors,” an unnamed independent power producers office bearer told the Post recently. “We have discussed the matter with officials of the Indian Embassy and the Central Electricity Board of India, and they have made it very clear that they are unlikely to buy electricity from projects with Chinese investment.”

The Procedure for Approval and Facilitating Import/Export (Cross Border of Electricity) by the Designated Authority, introduced by the Central Electricity Authority under India’s Power Ministry, has imposed restrictions on power trading if there is investment from a country generating electricity with which India shares a land border and a third country sharing a land border with India, which does not have a bilateral agreement on power sector cooperation.

Though this procedure does not directly talk about barring electricity with Chinese investment from entering India, Nepali officials and private sector representatives believe the provision is aimed at China-invested projects.

“There is a lot of pressure on the government and also an unfavourable investment environment,” said Mohan Bhatta, a professor at Dadeldhura Multiple Campus, who holds a PhD in far west culture.

“At the last stage of his political stint, Prime Minister Deuba is facing extreme pressure from locals, his constituency, to build the project,” Bhatta added. “Deuba is facing pressure from his party leaders equally strongly.”

Bhatta, the chief of Investment Board Nepal, too is from far west Nepal, and he is optimistic.

According to him, a high-level study team comprising secretaries from the Finance, Energy and Law ministries, including experts from the private sector under the coordination of the vice-chairman of the National Planning Commission is in the final stages of preparing a project financing report.

The study team has been given a March 12 deadline to submit the report. According to Bhatta, data collection and a revised social and rehabilitation cost of the project is also underway.

“There is no doubt that it can be built with domestic investment,” said Bhatta. “A study report is being prepared for a larger investment plan to rope in private investors and settle land acquisition issues,” he said.

“Most of the issues can be resolved within a month,” Bhatta said. “There is a possibility of moving forward some projects like road access to the project site and transmission line from the coming fiscal year,” he said.

But independent experts don’t buy the government’s lofty idea.

Hemraj Panta, a former registrar of Far Western University, bluntly says it is impossible to build West Seti without addressing India’s interest.

“It is not possible to construct the project with Nepal’s investment only,” he said. "There is a recent communication from India that they cannot buy electricity from a project that has investment from countries other than Nepal or India,” he said. “This is a clear message for the West Seti project as well.”

Despite being rich in natural resources, the far west region, including Karnali, has remained underdeveloped for decades and comes at the bottom of the human development index.

A multi-billion-dollar 10,800 megawatt Karnali Chisapani Multipurpose Project has been proposed in the lower basin since the 1960s, but the major obstacles of an agreement on cross-border water benefits and the major environmental and social impacts that will result from this project are likely to prevent development, according to reports.

“A large number of people in the far west are still waiting for major development to happen for a long time,” said Harka Bahadur Dhami, a retired teacher from Baitadi. “Human development is at a standstill in over a dozen villages.”

People are yearning for development that will be brought by the West Seti project.

“There is not only poverty and a low human development index, there is anger and anxiety among the people as well,” Dhami said.

Prime Minister Deuba, who has been in power for a long time, has done nothing for his constituency, according to senior leaders of the Nepali Congress. The door to development in far west Nepal still has not opened.

Narendra Khadka, former president of the Doti Chamber of Commerce and Industry, said people are still hopeful that Deuba who linked Karnali to the rest of the country by constructing 22 bridges will bring development and prosperity in the region by constructing the West Seti project.

“We are exerting pressure. The project should be constructed at any cost,” said Bir Bahadur Balayar, former minister and a Nepali Congress leader. “We have been lobbying for development. The project should not be made a political issue.”

Meanwhile, Saud, who says he is the lone survivor among the porters who worked for the project, wonders if he could see the electricity generated from West Seti.

“Will I be able to see electricity generated from the project?” said Saud. “Age is not on my side. Will I still be alive when the project is completed?”

14.35°C Kathmandu

14.35°C Kathmandu