Money

#NepalNow campaign back to reassure travellers after unrest

Tourism board revives social media drive after Gen Z protests triggered mass cancellations.

Sangam Prasain, Ramesh Kumar Paudel & Deepak Pariyar

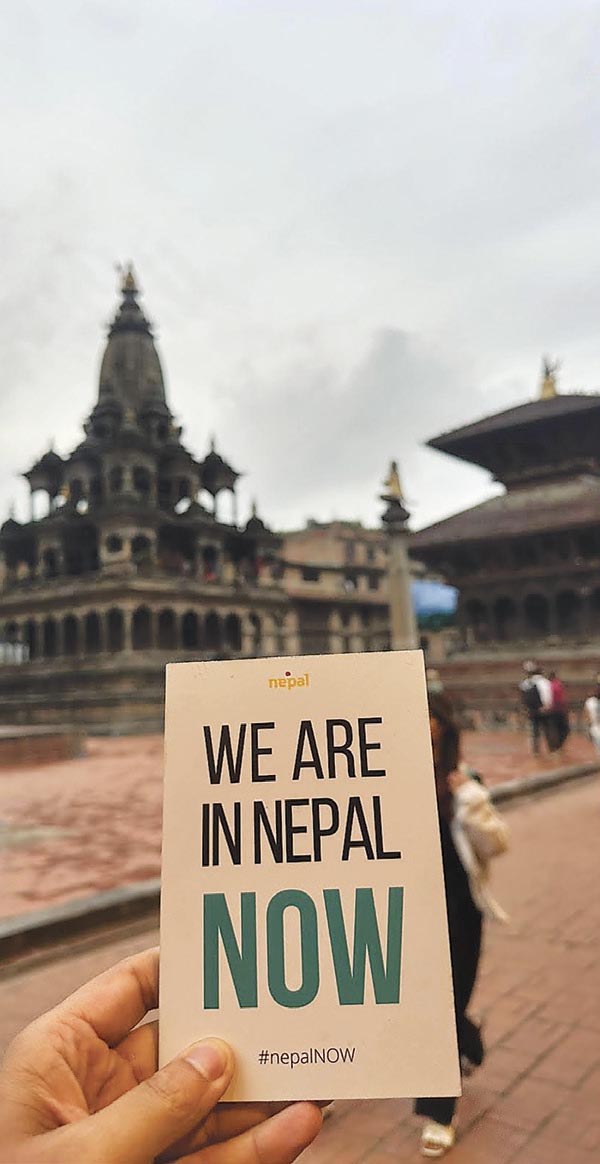

The Nepal Tourism Board’s once-successful hashtags—#NowInNepal, #NepalNow, and WE ARE IN NEPAL NOW—have made a comeback. They were earlier employed in the aftermaths of the 2015 earthquakes and the Covid pandemic.

The national tourism promotional body relaunched its campaign on social media with a sense of urgency, hoping to stem the sharp decline in tourist arrivals. This comes as the country’s tourism industry reels from the Gen Z protests of September 8 and 9—an anti-corruption uprising that quickly escalated into days of violence, arson, and bloodshed, shaking the sector at its peak season.

Deepak Raj Joshi, the board’s CEO, acknowledged how fragile travellers’ trust can be.

“We have been holding discussions on restoring travellers’ confidence and showcasing Nepal as a welcoming destination,” he said, adding that the campaign would highlight Nepal’s enduring strengths—its rich culture, breathtaking natural beauty, and adventure experiences that have long drawn the world to its mountains and valleys.

“This is the campaign where tourists themselves will hold a placard with hashtag #NowInNepal and tell the world about Nepal’s real situation,” said Joshi. “Following its success, this social media campaign launched by Nepal has been replicated in a number of countries.”

Still, Joshi admitted that timing was not on their side. The protests had erupted just as Nepal’s prime tourist season was beginning, leading to mass cancellations and casting a long shadow over hopes of recovery.

According to him, from September 1 to 8, the average tourist arrivals via air were 3,120 per day. But from 9 to 14, arrivals dropped to 1,300 per day, which is a 40 percent fall.

He added that arrivals are recovering. The average daily arrivals from September 17 to 20 is 2,200.

The scars go beyond perception.

Nepal, still struggling to find its footing after a decade-long Maoist insurgency (1996–2006), the royal massacre of 2001, the devastating earthquake of 2015, and the Covid pandemic, had pinned its hopes on tourism as a lifeline for its fragile economy.

Yet political instability, corruption, and erratic policy-making have continued to drag the country into a slow-growth trap, dimming prospects of a sustained rebound.

Last fiscal year alone, nearly a million people—migrant workers and students alike—had left Nepal in search of opportunities elsewhere.

The World Bank and the Asian Development Bank had pointed to tourism recovery as a cushion against this economic stagnation, noting the visible boom in the hospitality sector. Hotels bearing international brands were rising in Kathmandu, Pokhara, and beyond, promising new jobs and revenue.

Then came the protests, dashing those fragile hopes.

The Hotel Association Nepal did the maths.

Damage worth Rs25 billion had already been inflicted, they said, with nearly two dozen hotels severely affected by the rampages in early September. Images of flames consuming the Hilton Hotel in Kathmandu flashed across global news and social media feeds, reinforcing fears and convincing many tourists to abandon their plans.

Far from the capital, the ripples spread quickly.

In Chitwan, the monsoon had just eased, and the towns bordering Chitwan National Park—Sauraha, Patihani, Meghauli, Amaltari, and Pithauli—were preparing for the annual flood of visitors.

The festival season always marks the second busiest tourism season of the year. But this year, just as elephants and jeeps were being readied for safaris, the Gen Z protests exploded across the country.

The government cracked down heavily on the first day. Protesters retaliated with arson the next. Suddenly, the jungle resorts stood half-empty.

Mahesh Khanal, a hotelier in Sauraha, recalled the abrupt silence.

On September 8, he hosted 40 Chinese and Indian guests. But after they left, no new vehicle arrived at his property. “Guests are now few and far between,” he said, describing how cancellations piled up by the day.

“Corporate bookings through November are gone. Tourists are not coming. Even advance bookings are being scrapped. There is no chance of government or NGO seminars being held. Overall, the signs are not good.”

Khanal, who also serves as general secretary of the Regional Hotel Association in Sauraha, said his colleagues across the town reported the same. Cancellations are sweeping through the industry.

Chitwan National Park, home to the endangered one-horned rhinoceros and the elusive Royal Bengal tiger, usually attract 300,000 tourists each year. They come for jeep rides into the jungle, elephant treks through buffer zone forests, canoe trips down quiet rivers, or guided nature walks. But this year, even the elephants have stood idle.

“Normally, after mid-August, demand peaks. Thirty-five or thirty-six elephants would go out daily,” explained Dipendra Khatri, chairman of the United Elephant Owners Cooperative. “But after the protests, tourists have practically disappeared. It’s not zero, but only three or four elephants are going out now.”

The jeep safari operators, too, faced the pinch. During the monsoon, their trips were suspended, but October always brought a revival.

Rishi Tiwari, chairman of National Park Safari Pvt. Ltd., said they were preparing to deploy 32 new jeeps with comfortable seating and new routes from the first week of October. “But the national situation has shaken confidence,” he admitted. “Still, we are hopeful. The long holidays are starting, and we expect people to travel.”

Despite the chaos, the physical infrastructure in Chitwan remained unharmed. Khanal stressed that this was an opportunity. “If we promote the fact that tourism sites and infrastructure are safe, both domestic and foreign visitors will come,” he said, trying to inject some optimism.

In Pokhara, however, the damage was far more visible. The protests had left six hotels, resorts, and restaurants in flames. The trekking season in the Annapurna region, which typically peaks in September and October, was already faltering. Foreign trekkers, who had booked months in advance, were pulling out.

Krishna Acharya, president of the Gandaki chapter of the Trekking Agencies’ Association of Nepal, estimated that about 40 percent of trekkers had cancelled. Hotels were bearing the brunt too.

“September bookings have collapsed,” said Laxman Subedi, president of the Hotel Association Pokhara. “For October, new reservations are limited. Some tourists are cutting their trips short and leaving early. The flow of Indian visitors has also dropped, leaving the market eerily quiet.”

Before Covid, Pokhara’s hotels had boasted occupancy rates of up to 98 percent during the peak. This September, they stood half-empty, their lobbies hushed.

Just three weeks before the Gen Z protests erupted, tourism entrepreneurs in Bhairahawa estimated that around 5,000 Indian nationals were crossing into Nepal daily through the Belahiya border point.

According to Sagar Adhikari, former president of the Lumbini provincial chapter of the Nepal Association of Tour and Travel Agents, about half of these visitors continued on to Pokhara, 40 percent headed to Kathmandu, and the remaining 10 percent travelled to Chitwan.

Nepal welcomed 1.14 million tourists last year, a 13 percent rise from 2023, though still below the pre-pandemic high of 1.2 million. In the first eight months of this year, 736,562 tourists had arrived, suggesting a possible rebound.

But the protests struck just as momentum was building, leaving hoteliers, guides, and trekking agencies scrambling.

The stakes are high.

According to the World Travel and Tourism Council, tourism contributed Rs327.9 billion ($2.5 billion) to Nepal’s economy in 2023, supporting 1.19 million jobs directly and indirectly. Now, with confidence shaken and bookings evaporating, the industry faces yet another uphill battle.

14.12°C Kathmandu

14.12°C Kathmandu

1.jpg)

.jpg)