Money

Nepalis working abroad keep home fires burning

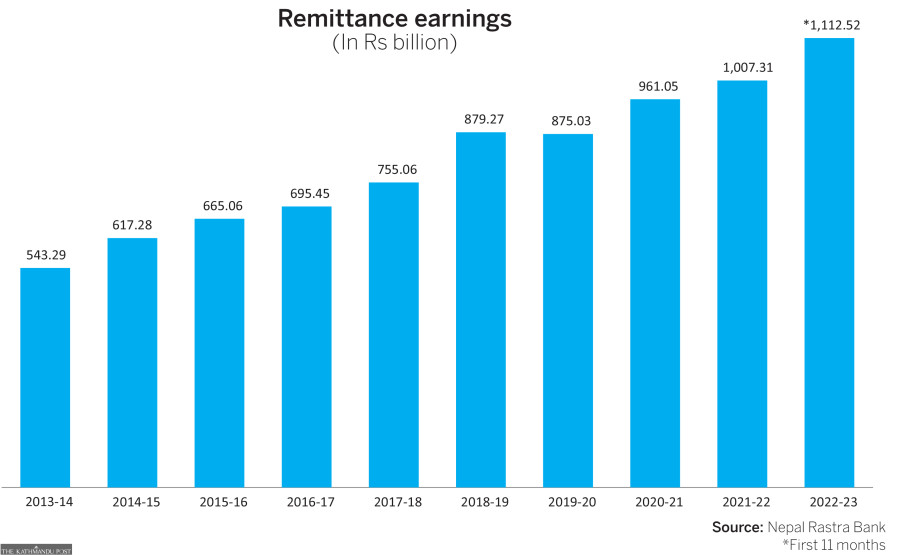

Remittance inflows totalled a staggering Rs1.11 trillion in the first 11 months of the fiscal year ended mid-June, the central bank says.

Sangam Prasain

As the migration of Nepali youths to foreign lands hits all-time highs, the cash they are sending back home is also setting new records.

Nepal Rastra Bank says remittance inflows amounted to a staggering Rs1.11 trillion in the first 11 months of the fiscal year ended mid-June. The river of money represents a 22.7 percent increase year-on-year.

During the same 11-month period, Nepal issued labour permits to nearly 720,000 outbound youths, the central bank said.

Gunakar Bhatta, spokesperson for Nepal Rastra Bank, says the massive remittance inflow has mellowed ongoing liquidity constraints.

According to the Department of Foreign Employment, the number of Nepalis working abroad started to increase after 2000 when the Maoist insurgency that started in 1996 reached a peak.

In the fiscal year 2000-01, just over 55,000 Nepalis went abroad. With the country’s economy in tatters due to the bloody fighting, Nepali youths had no choice but to seek their fortunes in other lands.

In the last two decades, remittance inflows have swelled nearly 25-fold from Rs47 billion in 2000-01 to Rs1.11 trillion in the first 11 months of 2022-23.

Remittance is the lifeblood of Nepal’s economy and is associated with improved health and social indicators.

A survey conducted by Nepal Rastra Bank in 2014-15 in 16 districts comprising 320 households shows that 25.3 percent of the money received from migrant workers goes towards repayment of the loans taken by the households, 23.9 percent is spent on buying food, clothes and other daily essentials, 9.7 percent on education and health bills, 3.5 percent on marriage and other social occasions, and 3 percent on buying assets like land.

Similarly, 28 percent is put aside in savings and 1.1 percent is invested in businesses.

“The money sent home by Nepalis working abroad has played a crucial role in lifting people from poverty. It has increased the living standard of Nepalis,” said Bhatta.

Various studies have shown that a 10 percent increase in the share of remittances in a country’s GDP leads to a reduction of 1.6 percent of people living in poverty.

In Nepal, poverty dropped from 25.2 percent in 2010 to 16.6 percent in 2019, largely due to a rise in remittance earnings, the central bank study shows.

But there are negative aspects of remittance too.

“If young people keep moving out at this rate, it may severely hit consumption levels,” said Bhatta. “Similarly, in the coming years, Nepal may face a severe labour shortage.”

Experts say that if Nepal fails to develop appropriate policies to retain its youth in the coming years, the bulging youth population and labour force may even become a curse.

While Bangladesh is experiencing rapid demographic changes accompanied by age-structural transitions, it is also creating a window of opportunity for potential demographic dividends over the next three to four decades, according to a report.

Currently, about 45 percent of its population is aged below 24 years, and 70 percent is aged below 40.

In Nepal, the census showed that the country has a 62 percent working-age population, aged 15-59 years. As per international practice, the 15-64 years age group is considered working age. The share of this age group is 65 percent of the total population in Nepal.

“Having such a large working-age population is considered a demographic window of opportunity. The theory is that the country can achieve rapid economic growth if we can mobilise this working-age population to boost production and accelerate nation-building,” Prof Yogendra Gurung, head of the Central Department of Population Studies at Tribhuvan University, told the Post in a recent interview.

A country’s ability to achieve economic development by mobilising its working-age population is called its demographic dividend.

“The government’s policy now should be to take advantage of this window of opportunity. The nation has to invest heavily in health and education. The goal should be to enhance the skills of the population of this age group,” said Gurung.

“Political uncertainty has led to massive brain drain,” said Jeevan Baniya, a labour expert. He estimates that the total labour permit issuance could reach 800,000 by the end of this fiscal year and the figure could keep rising each passing year.

“Due to political instability, corruption and low economic growth, there are no jobs in the country. Every young Nepali is concerned about attaining a better life,” he said.

In a new trend, hordes of Nepalis are now leaving for developed nations like Australia, the United States, the United Kingdom, Canada and Japan, and chances of their returning to Nepal are slim, experts say.

“Developed countries are facing labour shortages after Covid,” said Baniya.

“Remittance may boom in the future, but there are side effects too. Nepal may not be able to experience its demographic dividend in the years to come,” said Baniya.

The trend of students going abroad, apart from migrant workers, is more worrying. Universities in Nepal have reported a massive drop in student enrolment.

The central bank said that travel payments, or money spent to go abroad, increased 37.9 percent to Rs119.99 billion, including Rs89.18 billion for education, in the first 11 months of the current fiscal year.

In the labour segment, the increase was due to wage rises and strong labour markets in the Gulf Cooperation Council countries—Bahrain, Kuwait, Oman, Qatar, Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates—and Malaysia.

Malaysia was the top labour destination receiving 247,780 Nepalis in one year, followed by Qatar (122,828), the UAE (105,005) and Saudi Arabia (104,749), according to the central bank.

According to the Department of Foreign Employment, in 1993-94, the total number of Nepalis leaving the country for jobs abroad was just 3,605 individuals.

At the height of the Maoist insurgency in 2000-01, the number rose to 55,000 and started swelling rapidly to reach 527,814 individuals in 2013-14.

Even after the end of the insurgency in 2006, Nepal’s economy was stuck in a low growth trap due to topsy-turvy politics, decade-long power cuts and natural calamities like earthquakes.

The low growth trap prompted thousands of Nepali youths to rush out to seek greener pastures abroad.

19.6°C Kathmandu

19.6°C Kathmandu