Editorial

Plain truth

The hill-to-plains migration is starting to assume dangerous proportions.

The latest census report, which was made public on Friday, encompasses various striking trends and brings some pressing issues to the fore. It has further substantiated the general assumption about the growing demographic imbalance between the country’s hilly and Tarai regions. According to the report, 53.61 percent of the country’s population now lives in the southern belt, which makes up just 17 percent of the country’s landmass. The corresponding population figure was 50.27 in the census conducted a decade ago.

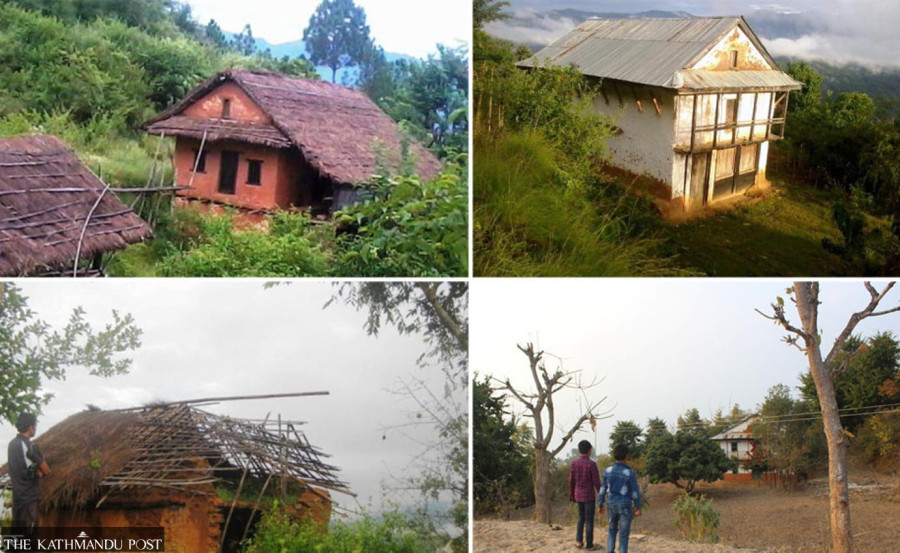

The new census shows the country’s population has disproportionately shifted from the northern hills to the southern plains, and from the villages to a handful of urban areas. The concentration of population in specific areas can have serious implications. While the census highlights the necessity of stopping the hills and mountainous regions from becoming barren, it is as important to protect the fertile lands of Tarai from turning into a concrete jungle in the image of Kathmandu and some other major Nepali cities.

The demographic picture has drastically changed in the past couple of decades. From 1960 until the 1980s, the state encouraged people to migrate to the plains to ease the population pressure in the hills and cultivate the large swathes of unused lands in the southern belt. But the pace of this migration has been so quick, many hilly villages are now turning into ghost towns. It is an alarming development for our planners and experts. But taking initiatives for planned development with long-term vision is not a strong suit of our political leaders. When they act, it is mainly because a particular development project will result in personal monetary gains. Seldom is their action motivated by public interest.

Yet it has now become imperative to act on the data of the latest census report. One way to stop the hill-to-plains migration could be by hastening the Mid-hill highway project that connects hill districts from Panchthar in the east to Baitadi in the far-west. Ten towns have been planned along the highway. If the project comes to fruition, the scattered populations of the hills can be encouraged to congregate in these areas. But the project, which began nearly two decades ago, is progressing at a snail’s pace. The project needs to be speeded up. Only such planned settlements with enough income-generating opportunities, and decent education and health services can retain people in the hilly and mountain regions. As added incentives, the government can start agro-based and other entrepreneurship projects in these settlements.

Worried about the emptying villages, some rural municipalities in the hill districts have started offering cash and other incentives to encourage reverse migration. There are also examples of successful adventure tourism ventures in hilly districts. Better connecting roads and availability of reliable electricity will be more reasons for people to come to live in these settlements. There is not a moment to lose. If Nepalis continue to move away from the hills at the current rate, there is a risk of most of the country being emptied of people, with a concomitant loss to the environment and the national economy. The loss of a way of life will be no less sad.

9.12°C Kathmandu

9.12°C Kathmandu