National

Continuing crowding of the Tarai creates multiple concerns

Planners say time has come to push for reverse migration by developing urban centres up in the hills.

Prithvi Man Shrestha

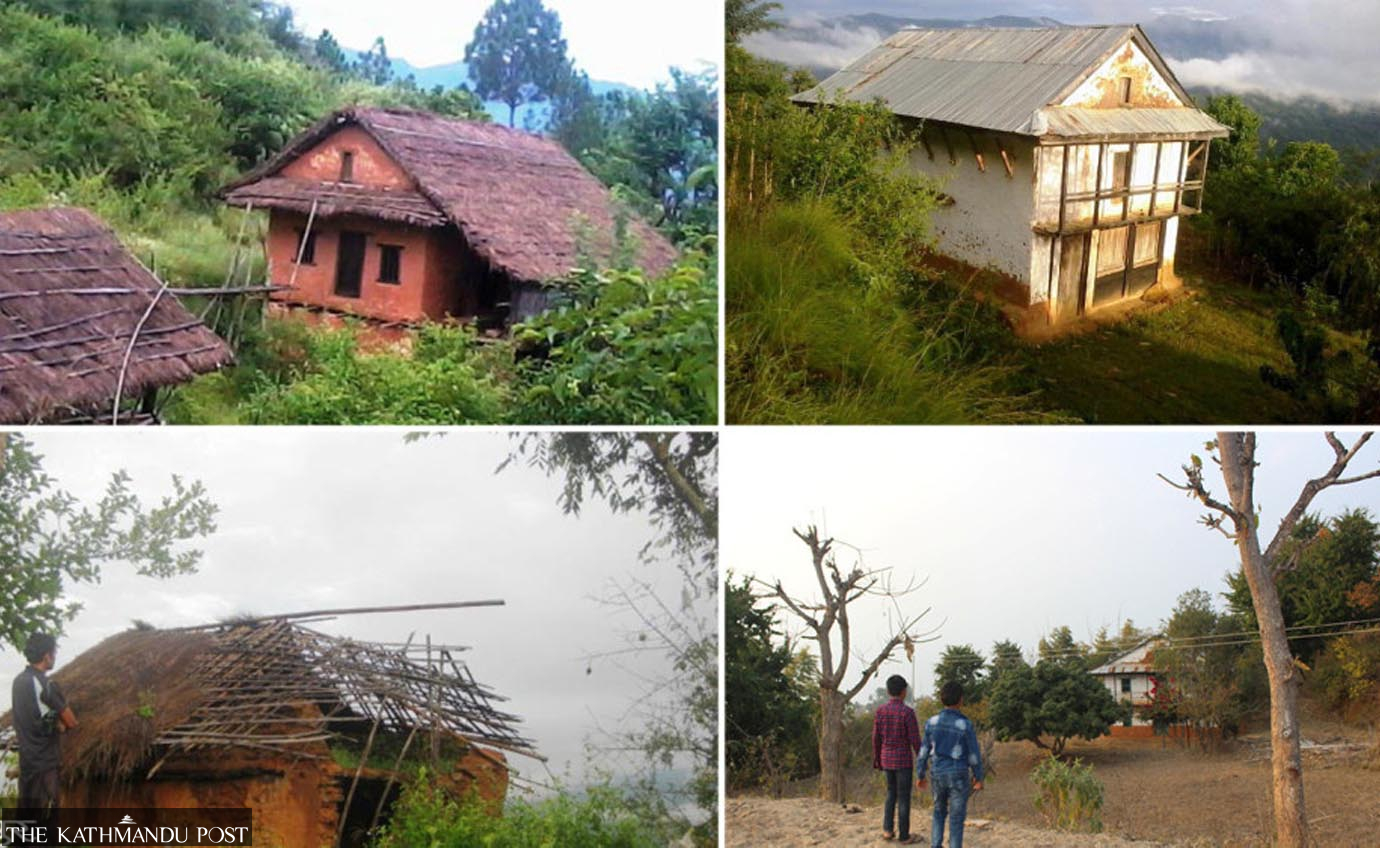

Rising migration of Nepalis from hilly regions to the Tarai is leaving large swathes of the hills barren while overcrowding the plains, which make up just 17 percent of the country’s landmass.

According to final data of the Population Census 2021 released on Friday, the southern belt hosts 15,634,006 people, 53.61 percent of the country’s total population of 29,164,578.

As per the 2011 census, the Tarai was home to 50.27 percent Nepalis. The population of both hilly and mountainous regions shrank rapidly in a decade since 2011, according to the new census data.

In the decade until 2021, the share of the hill population came down to 40.31 percent from 43.01 percent while mountain dwellers decreased from 6.73 to 6.08 percent.

Development experts and planners said growing migration to the Tarai region has caused the agricultural land there to shrink. As housing takes up more space in the country's food basket, Nepal could grow more food-insecure in the future.

They stress that systemic planning of human settlement has become urgent to save agricultural land in the plains from shrinking more rapidly.

Growing migration to Tarai from the hilly regions is a reality at present, said Jagadish Chandra Pokharel, former vice-chairperson of the National Planning Commission (NPC). “What we need to do is stop haphazard settlement on agricultural lands. We must promote concentrated settlements to limit land use and ease the delivery of services.”

Planners call for specific policies to discourage people from migrating from the hills to the Tarai. They suggest developing large urban centres in the hill, particularly along the Mid-Hill Highway, and creation of new economic and job opportunities.

Pokharel said various pocket settlements should be developed in the hilly regions where people from the rural areas could migrate, live and work. “Even the people who could not migrate to hilly urban centres from rural areas should be incentivised to do so as it would reduce the cost of providing basic services such as roads, drinking water, and electricity.”

Because of outmigration, the population in 34 of the 77 districts has decreased. All these districts are hilly and mountainous, according to the census. Ramechhap, Khotang, Manang, Bhojpur and Tehrathum witnessed the highest decrease in population in the decade.

The populations of Tarai districts and big towns are growing, the census revealed. Bhaktapur, Rupanedhi, Chitwan, Banke and Jhapa topped the list of districts with highest population growth. Marriage is the main source of migration followed by dependence, employment and study.

Nepal’s rulers earlier had made planned efforts to populate the Tarai, thereby decreasing the population pressure in the hills. In 1964, during the Panchayat regime, Nepal Punarvas (Resettlement) Company, a government owned but autonomous body, was formed to resettle the hill population in the Tarai.

The Nawalparasi Resettlement Project was launched that year, followed by the Khajura project in Banke in 1966. Eight other resettlement projects were launched by 1977. Under these schemes, 6,000 families were relocated. During the fifth periodic plan (1975-80), three more projects were launched in Bardiya, Kailali and Kanchanpur and a total of 1,945 families resettled, according to a bulletin published by the Centre for Nepal and Asian Studies (CNAS) of the Tribhuvan University in 1983.

Now, people are descending voluntarily and on a larger scale from hilly and mountainous regions.

Former government secretary and urban planner Kishore Thapa said time has come to introduce a policy to encourage reverse migration.

“We can do so by running planned urbanisation schemes in various pocket areas and developing good infrastructure, creating health and education hubs and developing industries including tourism, animal husbandry, and those based on water resources,” he said.

Not that urban centres have not been developed in hilly regions but people continue to migrate to the Tarai. “This is happening as various hilly regions are urbanising without creating enough economic opportunities for the people,” said Sanjaya Uprety, general secretary of Regional and Urban Planners’ Society, an agency of urban planners.

“We have to develop urban planning for the hilly regions under the urban-rural partnership model so that people from the rural areas also get economic opportunities there.”

Uprety, an associate professor of urban planning at the Institute of Engineering, Pulchowk, said settlements in the Tarai too should be developed under the concept of ‘urban regions’ by integrating several urban centres. This in turn will help establish bigger markets for the produce of hilly regions and encourage people to stay there.

Growing population in the Tarai has been eating up its limited unpopulated land. Development and urban planners say time has come to ensure optimal use of the land for human settlement in Tarai considering the shrinking share of unpopulated areas.

“We should encourage the development of compact and dense settlements in the Tarai,” said Thapa. “We need to promote group housing and high-rise buildings, instead of scattered housing facilities which will help minimise the use of land in addition to helping the state provide facilities at lower costs.”

Growing population of the Tarai could also tilt the political power towards the region, as well as to the urban areas, as electoral constituencies are determined based on population though geography is also taken into consideration.

Hilly and mountain regions which have been deprived of development opportunities might be further ignored if political power concentrates more on the Tarai, said Pokharel.

18.12°C Kathmandu

18.12°C Kathmandu