Sports

Despite scant resources, Nepal’s para-fighters keep kicking

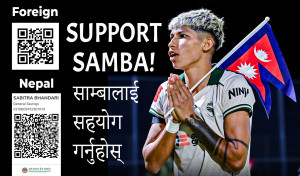

After guiding Nepal to its first-ever Paralympic medal, volunteer coach Kabiraj Negi Lama is training five athletes. But Lama has no job, no recognition, and minimal state support.

Nayak Paudel

Every morning, except on Saturdays, Kabiraj Negi Lama walks into a modest taekwondo hall of the Nepal Taekwondo Association building in Satdobato, Lalitpur. The sun has barely risen, but the space is already abuzz with the echoes of powerful, menacing kicks hitting paddle targets and the sharp “aah!” of athletes pushing their limits.

They are para-taekwondo players—five of them—all chasing the same dream: medals for the country. And Lama is their coach—unpaid, unrecognised, but still holding on.

Less than a year ago, Lama helped Palesha Goverdhan win Nepal’s first-ever medal at the world’s biggest multi-sport stage—a bronze in the K44 -57kg category at the 2024 Paris Paralympics.

It was a moment of historic pride. Flags waved. Speeches were made. Promises poured in.

Among them was a simple one: Lama would be given a formal coaching role.

But nearly a year later, Lama, under whom Nepal has secured 11 official international medals, including three gold, two silver, and six bronze, is yet to be appointed.

By day, Lama works at the All Nepal Football Association (ANFA). By early morning, he volunteers his time, training the next generation of para-fighters—Bharat Singh Mahata, Amir Bhlon, Dipesh Mahat, Kamana Prasai, and Renu Tamang—who are now preparing for the 10th Asia Para Taekwondo Championships, a G4 category event, in Kuching, Malaysia.

Goverdhan (-57kg), Mahata (-58kg), Bhlon (-63kg), Prasai (-47kg), and Tamang (-47kg) will be leaving for the tournament on July 29, with their bouts taking place on August 1. “Mahat, who does not have both of his hands, will not join us as his category did not have enough players,” Lama said. “Goverdhan will join us in Kuala Lumpur directly from China, where she is pursuing her bachelor’s in architecture engineering. We will then head to Kuching together.”

The Kathmandu District Taekwondo Association and Nepal Chamber of Commerce (NCC) bid farewell to the squad at an event on Saturday.

“It’s a big tournament,” Lama said. “A good result here could open doors for our athletes for LA 2028.”

A medal, but no job

Lama’s own Olympic dream had ended years ago—he was a promising taekwondo athlete, but was often outmatched due to his shorter height.

“My height wasn’t on my side,” he said. “So, I thought maybe I could make it as a referee, just to be part of the Olympics.”

That path, too, closed. But during referee training, Lama learned something that reshaped his purpose: the Olympics and Paralympics were of equal stature, organised under the same structures and values. Pulling up the official social media pages of Paris 2024, LA 2028 and Brisbane 2032, he shows their profile pictures. “The emblems of the Olympics and Paralympics are side-by-side. These matching logos say it all,” Lama said.

“My dream was to reach the Olympics. I couldn’t do it as an athlete, but I became part of a medal-winning team. And now, others are chasing the same dream. I can’t walk away from them.”

Dreams on Rs100 a day

The five athletes Lama trains are determined but financially strained.

They get just Rs100 a day from the association for training, which barely covers transport cost. A separate Rs500 daily stipend under the government’s ‘Mission 26’ programme, an initiative aimed at securing a gold and double-digit medals at the 2026 Asian Games, was also recently cut at the end of the fiscal year 2024-25, citing budget constraints. Lama was among its recipients.

In martial arts, where a practitioner needs good nutrition and diet to stay fit while focusing on preventing injuries, a couple of hundred rupees is dirt in the desert. Still, the athletes keep showing up.

Take Bharat Singh Mahata. He hails from a village near Lipulekh, one of Nepal’s most remote border regions. Born without his left hand below the elbow, Mahata initially played volleyball but had to stop due to the lack of inclusive opportunities.

He came to Kathmandu in 2015 in search of some para-sports to join.

“I looked up one-hand cricket on YouTube and even tried wheelchair cricket in Kathmandu,” he recalled. “But nothing worked out.”

Disheartened, he returned to his village, a journey that still takes over two days, with hours of walking from the final bus stop.

In 2023, he came back to the Capital after hearing about para-taekwondo and met Lama.

Just two years in, he is already considered one of Nepal’s most promising fighters.

“I just wanted a space where I’d be recognised for my talent,” he said. “People like us aren’t given proper jobs. We’re not seen through the same lens. With wins in major tournaments, I want to change the way we are seen.”

Now 27, Mahata is married, has a young son, and supports three sisters. He keeps cows to sell milk and helps run the household.

“Rs100 may sound like nothing, but it’s what kept me going,” he said. “Whether taking a bus or buying a bottle of water, I think a hundred times before spending money. I know I’m getting almost nothing from the state, but at least that amount has kept me going.”

Mahata also returns in the evenings from Kirtipur to train with able-bodied taekwondoins, pushing himself to perform at an even higher level.

Gold, not survival

Inside the training hall, two A4-sized papers hang on the wall: one bears the LA28 logo, the other, the 2026 Asian Games emblem. Mahata taped them up himself.

“Paris was tough,” he said of the Paralympics, where he failed to progress towards a medal. “But the Asian Games in Japan and the Paralympics in LA—they won’t be the same. This time, I’m not training for bronze or silver. I aim for gold.”

The ambition has caught on. Amir Bhlon, who took up the sport on October 24, 2021, a date he clearly remembers, begins his morning routine by circling the Satdobato sports complex seven times—his warm-up ritual.

“I’ll keep getting better and better,” he said. “I want to win medals on the biggest platforms.”

Each of the athletes shares a similar story: limited financial support, poor job security, and mounting personal responsibilities.

“There are no good jobs for people with disabilities in this country,” said Bhlon. “I used to work for an online platform—calling clients, reminding them of payment deadlines. But I left to focus on training. How I’m surviving now, even I don’t know.”

Yet, every morning, they return to that hall, their kicks sharper, their voices louder, and their eyes still locked on a brighter future.

Will the medal matter?

Lama believes the Paris bronze changed something. Since Goverdhan’s win, there’s been a visible surge in interest as more persons with disabilities are exploring para-sports, asking about opportunities, and showing up.

“Thanks to the hall and basic training equipment provided by the association,” Lama continued, “we can at least keep kicking and keep moving towards the dreams that seem impossible.”

But whether that interest is matched with institutional backing remains uncertain.

“If we don’t act now, we’ll lose them,” Lama said. “This can’t be a one-time story. There has to be a system in place.”

20.23°C Kathmandu

20.23°C Kathmandu