Climate & Environment

Tigers return in Nepal; their number now reaches 355

Nepal achieves the feat of doubling the big cat population as per its 2010 pledge. Focus now should be on sustainability and reducing conflicts, as conservation success has come at human costs, experts say.

Gobinda Prasad Pokharel

Nepal has become the first among the 13 countries that 10 years ago had pledged to double their tiger populations by 2022 to achieve the feat. The number of big cats in Nepal has reached 355, according to the latest count.

Prime Minister Sher Bahadur Deuba on Friday announced the tiger population, as per the census conducted in December last year, at a function marking the Global Tiger Day.

“Human-tiger coexistence is needed for the success of conservation efforts,” said Deuba, while unveiling the latest number of big cats in the country.

Ramchandra Kandel, director general of the Department of National Parks and Wildlife Conservation, said that effective implementation of the periodic tiger conservation action plan helped achieve the target.

The fourth nationwide tiger and prey survey was carried out in all the potential habitats between December 2021 and April 2022 in 24 districts. During the survey 316 individual tigers were identified in the photographs.

Photographs of 113 individual tigers in Chitwan, 117 in Bardiya, 35 in Parsa, 23 in Banke, and 28 in Shuklaphanta were captured.

Based on spatial capture-recapture estimate, the tiger population is estimated to be 41 in Parsa, 128 in Chitwan, 25 in Banke, 125 in Bardiya and 36 in Shuklaphanta, according to the report titled “Status of Tiger and Prey in Nepal” was also released on Friday.

The latest tiger number is a 51 percent jump from the last survey of 2018.

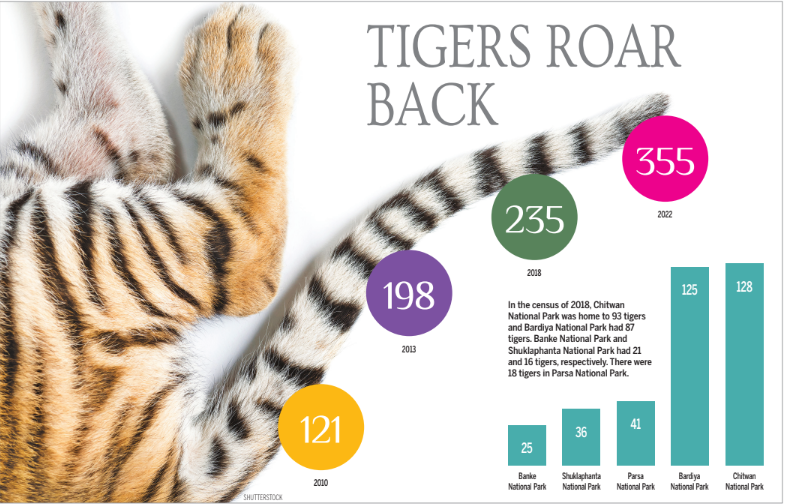

In 2010, there were 121 tigers in Nepal. The number rose to 198 in 2013 and 235 in 2018.

As per the new census, Chitwan National Park has 128 tigers, Bardiya National Park has 125, Parsa National Park has 41, Shuklaphanta National Park has 36 and Banke National Park has 25 tigers.

In the census of 2018, the Chitwan National Park was home to 93 tigers and Bardiya National Park had 87 tigers. Banke National Park and Shuklaphanta National Park had 21 and 16 tigers, respectively. There were 18 tigers in the Parsa National Park.

Amid celebrations that the tigers are roaring back in Nepal, concerns too have grown about their habitats, prey density—and above all the increase in human-tiger conflicts.

While Nepal’s tiger conservation efforts have been hailed globally, questions have also arisen, as the success has come at human costs.

Estimates suggest three people are attacked by tigers every month, when they are in the jungles or buffer zones to collect fodder and firewood or any other forest products. Tigers too have been reported to have strayed into human settlements in search of food.

In the last three fiscal years, 104 tiger attacks inside national parks and buffer zones were recorded, resulting in 62 fatalities. In 28 percent of such instances, people sustained serious injuries.

Tiger attacks on humans have substantially increased especially around Bardiya and Chitwan, according to the report. There has been regular tiger presence in the areas where people also visit frequently for fodder, fuelwood and other non-timber forest products.

The report says that with an increase in tiger population, territorial fights among tigers are also increasing as space available for them is limited, driving the wild cats to forest fringes and other areas where human activities are high.

The report made public on Friday says the total area occupied by tigers is 9,653.4 square kilometres of the total potential habitat of 18,928 square kilometres. Tiger density per hundred square kilometres in protected areas and adjoining forests is estimated to be 4.06 in Chitwan and 7.15 in Bardiya, according to the report.

Tiger population is spread in 16 districts—Rautahat, Bara, Parsa, Makwanpur, Chitwan, Nawalparasi East, Nawalparasi West, Dang, Banke, Salyan, Bardiya, Surkhet, Kalikot, Doti, Kanchanpur and Dadeldhura.

Chirnajibi Pokharel, a tiger expert who was involved in the research, said the increase in prey species also helped in achieving the new tiger population.

“Protection of habitats also helped in breeding and provided safe space for tigers to rear their cubs, leading to an increase in their numbers,” he told the Post.

Prey populations too played a key role. Spotted deer, sambar, hog deer, barking deer, blue bull, four-horned antelope, wild boar, gaur, rhesus monkey and langur are the animals on which tigers prey. The prey density per square kilometres in protected areas and adjoining forest is 75, 100, 33, 90 and 146 in Parsa, Chitwan, Banke, Bardiya and Shuklaphanta, respectively, according to the report.

Professor Tej Bahadur Thapa, head of the Central Department of Zoology at the Tribhuvan University, said there are major challenges in sustaining the current tiger population.

“Focus should be on maintaining the coexistence of tigers and humans amid rising conflicts near the protected areas,” Thapa told the Post. “Currently, we can’t say the tiger population in Nepal has reached a saturation point. The challenge in the days ahead is sustaining this population, as the numbers have been on an increasing trend. Conservationists should pay attention to prey resources and habitats.”

Rama Mishra, who is doing her PhD in small carnivores, said the rise in tiger-human conflicts outside the protected areas may be because community forests are well managed. Forests managed by communities make good habitats. And there are ample resources for tigers. This may be the reason why tigers are coming out from the core areas,” she told the Post. “And the pitfall is an increase in tiger-human conflicts. Now the focus should be on habitat management in the core areas.”

Pem Kandel, secretary of the Ministry of Forest and Environment, told the Post that the focus now will be on livelihood programmes and alternative ways for the people living near the buffer zones. He also said that effective implementation of wildlife-friendly infrastructure construction directives, 2022 will help reduce conflicts.

Experts concede that people and even conservationists have paid a huge price to increase the tiger numbers in Nepal.

Dr Ganesh Pant, an ecologist, said that more than 300 people, including conservationists and activists, have died in the last decade in tiger attacks.

The report, however, says tigers account for just 6 percent of the total human-wildlife conflict. The major conflicts are caused by elephants, leopards and rhinos, according to the report.

Research and monitoring programmes have been recommended for sustaining the tiger population.

Experts say that estimated ecological carrying capacity can provide crucial scientific inputs for preparation of site-specific habitat management plans.

According to Pant, assessment of ecological carrying capacity of the Banke-Bardiya landscape is currently ongoing. Previously in 2020, during such assessment, Chitwan’s tiger carrying capacity was found to have been 175.

Baburam Lamichhane, a wildlife biologist who was involved in preparing the report, said the increase in the number of tigers in Chitwan is due to the habitat management and prey availability.

“During the count of 2018, there were more than 52 females among the total 93 tigers. The cubs may have grown into adults and contributed to an increase in the population,” said Lamichhane. “In these four years, habitat restoration and grassland management have helped increase prey density as well. Zero-poaching also contributed to the rise in the numbers.”

Nepal has made remarkable progress in controlling poaching also since it committed to doubling the population.

Of the 228 tiger deaths in the last ten years, 202 died of natural causes and 26 were victims to poaching, according to Dil Pun, spokesperson for the Department of National Parks and Wildlife Conservation. “Some data, however, is missing,” he said.

Hari Bhadra Acharya, chief warden of the Chitwan National Park, admits the rising conflicts.

“We are seeing increasing conflicts between tigers and humans. Tigers are coming out of the core of the jungle to areas adjoining buffer zones,” Acharya told the Post.

According to Acharya, the major challenge is prey species availability inside the core area.

“Plenty of grasslands and wetlands inside the core jungle area are needed to reduce human-tiger conflict,” he said. “In the lack of those, tigers venture out of their territory in search of easy prey.”

13.2°C Kathmandu

13.2°C Kathmandu