Culture & Lifestyle

Nepali women should embrace their ‘Unsanskari’ selves

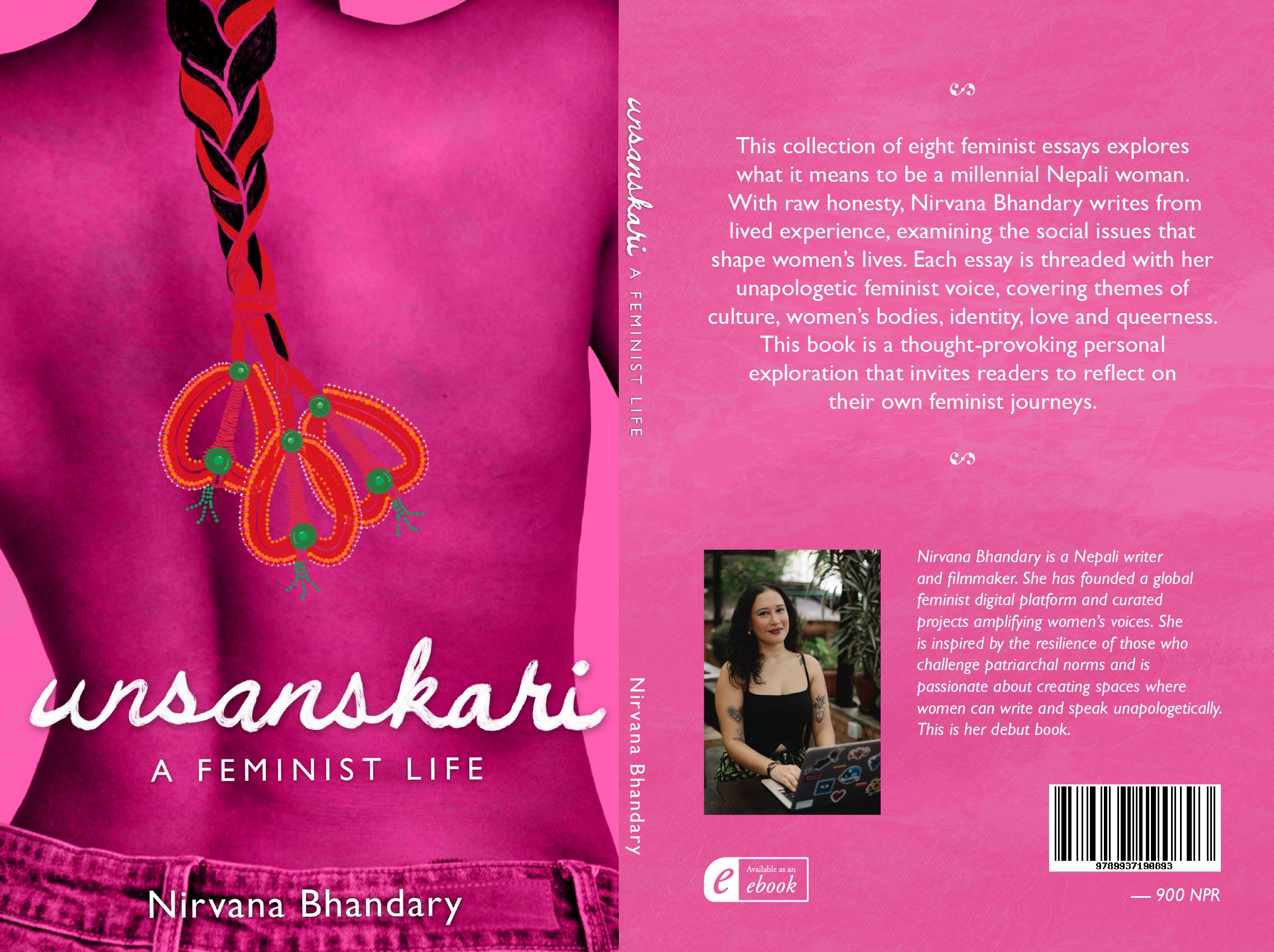

Writer and filmmaker Nirvana Bhandary discusses her debut book ‘Unsanskari: A Feminist Life’, and the importance of unlearning patriarchal norms.

Sanskriti Pokharel

Nirvana Bhandary is a Nepali feminist writer, independent filmmaker, and digital activist. She founded the online feminist storytelling platform The Feminism Project. She also wrote and directed the documentary ‘Moti, Dubli, Kali, Gori: Nepali Women Reclaim Their Bodies’, which explores Nepali women’s experiences with colourism and body shaming. ‘Unsanskari: A Feminist Life’ is her debut book.

In this conversation with the Post’s Sanskriti Pokharel, Bhandary reflects on her feminist journey, the cultural tensions that shaped her identity, and the importance of unlearning patriarchal norms to reclaim autonomy and joy.

‘Unsanskari’ is such a striking title. What does being ‘unsanskari’ mean to you personally?

I came up with the word ‘Unsanskari’. The fact that it comprises both English and Nepali—‘un’ being an English word, and sanskari being a Nepali word, is a reflection of my identity. I am a woman who walks the line between both worlds.

Since I was a little girl, I have always heard the word sanskari explicitly attached to women. A woman should be sanskari to be respected. But why should we be the silent, subservient bearers of a culture that is patriarchal in its traditions?

Gender roles are built into the very fabric of Nepali society, and I strongly critique that in my book. Through my writing, I aim to reassure my Nepali sisters that it is okay to defy social expectations and encourage them to embrace their ‘unsanskari’ sides.

Being ‘unsanskari’ means rejecting the parts of our patriarchal culture, society and traditions that do not prioritise our joy and liberation.

You’ve been a filmmaker, activist, and writer. What inspired you to express your feminist journey in book form this time?

Writing comes naturally to me, and it has been my best friend, therapist, lover, and parent. ‘Unsanskari’ is a collection of essays which I wrote over the last eight years. So, this book was coming together for a long time.

Which feminist writers, thinkers, or activists have influenced you, both globally and within Nepal?

More than them, it’s the women around me who have influenced me the most—my mother, grandmothers and the community of young Nepali women who want to live their most authentic, feminist lives.

How did living between Nepal and the West influence your sense of identity and feminism?

I had a cultural identity crisis growing up due to constant migration. The feeling of “not Nepali enough” and “not Western enough” still challenges my self-perception.

But looking at the positives, I have developed a multifaceted identity and a wide range of interests through my experiences in both worlds. My understanding of feminism has grown because of it.

What was the hardest part about being honest and vulnerable in your writing?

It was terrifying. But as I wrote more and more, I realised how many women were able to see themselves in my words. That gave me the courage to continue.

While I worked on my book, my editor encouraged me that at times I need to forget about the reader and write for myself—write my unfiltered truth. Whether that is received with praise or criticism is beyond my control.

The book talks about learning to preserve the beautiful parts of culture while letting the oppressive parts rot away. How can young Nepali women start doing that in their daily lives?

We need to challenge the sexist norms in our communities—in our homes, workplaces and schools to the best of our capacity.

Unlearning the narratives we have been fed growing up is crucial. We need to unlearn that we are not as strong as boys, that being pretty is more important than being smart, that menstruation is dirty, and that marriage and motherhood are the eventual purpose of our lives.

Unlearning is not easy or linear; it’s hard and often uncomfortable. It can be a lonely and isolating experience if the people around you push back against it and attempt to coerce you into continuing oppressive practices. But I have faith in the strength, intelligence and courage of young Nepali women.

In a chapter on women’s bodies and sex, you connect self-pleasure to self-autonomy. Why do you believe this topic is central to feminist activism?

Bodily autonomy is a core part of human rights. Patriarchy has restricted women’s control over their own bodies in a number of ways over the centuries: lack of access to contraception, criminalising abortion, and forced motherhood.

We are taught that our bodies are solely to be used as vessels for male benefit, whether that is through corporations and media sexualising us, or coercive sex. With all this history and context, regaining control and pleasure over our bodies is a feminist act and achievement.

Nirvana Bhandary’s book recommendations

The Beauty Myth

Author: Naomi Wolf

Publisher: Chatto & Windus

Year: 1990

A classic feminist text that reveals how beauty standards are used as a political weapon to discipline women.

Bitch Doctrine

Author: Laurie Penny

Publisher: Bloomsbury USA

Year: 2017

This book is a sharp collection of essays that covers politics, gender, class and online culture.

The Artist’s Way

Author: Julia Cameron

Publisher: Jeremy P Tarcher

Year: 1992

I highly recommend this timeless book by Cameron to anyone who wants to nurture their creative powers.

Feminism Is for Everybody

Author: Bell Hooks

Publisher: South End Press

Year: 2000

Hooks makes feminism feel warm and accessible. I love how she explains the core ideals without losing depth.

The Power

Author: Naomi Alderman

Publisher: Viking

Year: 2016

In this novel, girls and women can generate electric currents from their bodies, shifting the global balance of power.

15.12°C Kathmandu

15.12°C Kathmandu