Culture & Lifestyle

Nepal Vocational Academy aims to create both traditional artisans and modern workers

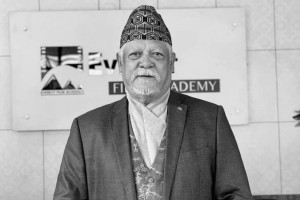

Established by Rabindra Puri, the academy has managed to provide skill training to hundreds in a span of just five years..jpg&w=900&height=601)

Shashwat Pant

In 2000, Rabindra Puri completed the construction of Namuna Ghar, in Bhaktapur, an old Newar residential building restored to blend ancient architecture with modern amenities. As the building received a lot of attention, and his work started gaining national traction, he decided to engage himself in building more architectural structures that pertained to the same idea of bringing together traditional designs with contemporary comfort. But the major challenge he faced while pursuing such projects was the lack of skilled human resources to turn his vision into reality.

Then, in late 2014, he established Nepal Vocational Academy in Panauti to produce skilled artisans, who are adept in traditional knowledge of wood carving, metal casting and stone carving.

“The idea of the academy was born out of desperation,” says Puri, who has also expanded his academy to Bhaktapur. “But it is one of the most important projects I am overseeing.”

The academy in Panauti was started with the help of a German organisation Schülen für Nepal. Puri and his team had a clear vision of what they want to yield from the academy and the students. But during their initial enrollment, they realised it wasn’t going to be easy to carry out the task they had undertaken. They received a lot of applications, but as the classes started, not many students took the job seriously.

“Many were quick to drop out,” says Mrigendra Pradhan, vice-principal of the academy. “That’s why we now interview candidates to see if they are serious about learning.”

But the importance of this project became more evident when just a year after they established the academy, the 2015 earthquake damaged many cultural heritages across the country.

“Of course, it was an unexpected and tragic event for the country. But it further established the need for more skilled artisans who are well versed in traditional architecture and its restoration,” says Puri, who trained in sculpture-making in Germany.

The academy in Panauti since its inception has created over 100 artisans. In order to produce more skilled workers, they have built another one in Ganchhen, Bhaktapur. While works have already started, Puri says that the academy in Bhaktapur will formally open from January 1, 2020. This one aims to create around 200 artisans a year.

Some of the graduates from the vocational academy in Panauti are employed by Puri himself. They are assisting in various projects undertaken by Puri, while some are passing on the skills they have learned to new students enrolled in the academy.

Dinesh Tamang, who is among the academy’s first batch of graduates, works as a teacher in the academy. Trained in wood carving, unlike most of his batchmates who weren’t serious about learning the craft and dropped out soon after they enrolled, the 25-year-old took the opportunity seriously.

“I feel grateful that I get to teach these young boys what I’ve learnt,” says Tamang. “This is how I contribute to preserving this traditional art form.”

But the academy in Bhaktapur is going to be a bit different from the one in Panauti, says Puri. While the one in Panauti is open and deals with traditional arts and crafts, the one in Bhaktapur deals with skills needed to provide service to regular households, such as carpentry, plumbing and electrician training, apart from learning traditional craftsmanship skills.

This, Puri hopes, will help in curbing the flow of Nepalis travelling abroad to work as migrant workers. And even if they decide to leave the country to make a good living, they are equipped with skills that can be helpful to them finding better jobs in foreign countries.

Even the classrooms in Bhaktapur are equipped with electricity boards in both Nepali and German systems. “We will also have visiting instructors from Germany to help our students learn the international methods,” says Puri. “We want to prepare our students so that they can work anywhere in the world. We ensure that their skill will sell everywhere.”

The response has been positive so far. He says a few people have even asked him whether they train in repairing elevators. “This was the motivation for us to expand our academy,” he says. “We wanted a space where we could produce as many skilled workers as we could.”

The academy charges a fee of Rs3,000 for the first three months, after which the training is free for another six months. For those who are from other parts of the country, there is also a hostel facility for students. The hostel fee is Rs12,000 for six months, after which lodging is also free.

“We also provide monthly salary after the students complete six months at the academy,” says Puri.

Puri, through the Rabindra Puri Foundation, has donated one ropani of land worth Rs 70 million, while Schülerhilfe für Nepal has donated Rs50 million to the academy.

This, though, is just the start, he says. In future, he wants to establish a vocational university to realise his vision. “Vocational education is quite important and I feel that we need more institutes like these so that Nepalis have a skill-set to sustain themselves,” says Puri.

20.12°C Kathmandu

20.12°C Kathmandu