National

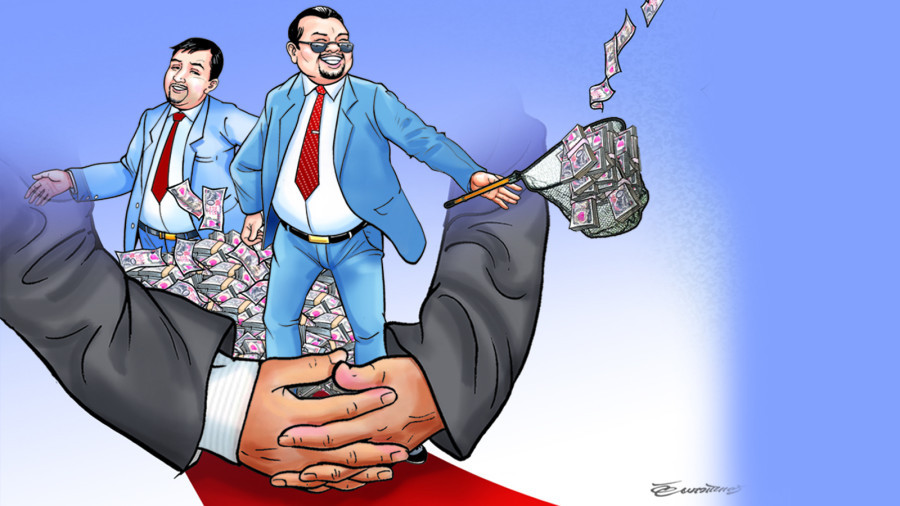

Prime minister’s reform pledge rings increasingly hollow

PM Oli-led Good Governance Commission has not met even once since its formation last month.

Purushottam Poudel

Instead of strengthening existing state agencies responsible for good governance, Prime Minister KP Sharma Oli formed a 15-member High-Level Governance Reform Recommendation Commission—also known as the Good Governance Commission—under his own leadership.

However, nearly a month since its formation, the commission has not held a single meeting.

The Cabinet on April 21 tasked the commission with studying issues related to public service delivery, structural administrative reforms, and good governance and submitting a report within six months. Yet, according to one of its members, Law Minister Ajay Kumar Chaurasiya, the commission has yet to begin its work.

He argued that the commission could not meet as the government was entirely focused on convening the Sagarmatha Sambaad, a three-day international dialogue, which ended on Sunday.

“Hopefully, it will meet soon,” Minister Chaurasiya told the Post on Monday.

But the government’s reluctance to do even the bare minimum such as making ministers’ property details public, ten months after the government’s formation, has made a mockery of its announcement to promote good governance, including through the commission.

Although there is no legal obligation to disclose the ministers’ property holdings publicly, the practice has long been seen as important to ensuring transparency, accountability, and public trust in state institutions.

Former home secretary Umesh Mainali, who also served as the chief of the Public Service Commission, says governments routinely made ministers’ property public following the 1990 political change.

But this practice was discontinued during the tenure of the election government led by then chief justice Khil Raj Regmi in 2013. Since then, some governments have revived the practice while others have ignored it.

“Even if it is not a legal obligation, it does not mean that previous disclosures were wrong,” Mainali adds. “Therefore, the government must either say the earlier idea of disclosing property details was wrong, or it should immediately make such disclosures.”

According to a notice published in the Nepal Gazette published on July 4, 2018, the prime minister, ministers and ministers of state have to submit their property details to the Office of the Prime Minister and the Council of Ministers. Such details should then be sent to the National Vigilance Centre within two months of appointment. It is a democratic practice to publish such details.

Section 50 of the Prevention of Corruption Act 2002 requires public office holders to submit their property statements within 60 days of assuming public office and at the end of each fiscal year.

“Whoever joins a public office shall, within 60 days from the date of joining the public office, and whoever is engaged in a public office on the date of commencement of this section shall, within 60 days from the date of commencement of this Act, and after that, within 60 days from the date of completion of each fiscal year, submit the updated statement of property in his/her name or the name of his/her family members, along with the sources or evidence thereof, to the body of authority,” reads the Act.

However, subsection 50(4) of the Act also allows for these details to be kept confidential.

Article 28 of the Constitution guarantees the right to privacy. As the constitution protects a person’s property, its disclosure is left to personal discretion.

“The privacy of any person, his or her residence, property, documents, data, correspondence, and matters relating to his or her character shall, except by the law, be inviolable,” reads the Article.

But Krishna Gyawali, a former secretary of the Nepal government, argues that publication of ministers’ property details should be mandatory as those in power might otherwise hide their assets.

“The public can see the differences in the properties of a minister from the time of their assuming office to the time they leave only if property details are made public. This helps them establish whether their government representatives are corrupt,” Gyawali told the Post.

Citing corruption as the main obstacle to the country’s progress, there have often been calls for the formation of a powerful judicial commission to investigate the assets of individuals holding public office since 1990.

Such demands have been raised not only by opposition leaders in the House of Representatives who seek to hold the government to account, but occasionally even by members of the ruling parties.

Former administrators also see the government’s decision to form the Good Governance Commission as unnecessary. The Good Governance Act of 2007 already provides for a monitoring committee chaired by the chief secretary. Besides, the Good Governance Regulations of 2008 stipulates the formation of another committee under the leadership of the prime minister. Given these existing legal provisions, they question the necessity of establishing yet another commission.

Mainali even questions how the prime minister-led Good Governance Commission can be expected to offer recommendations to another committee, which is also chaired by the prime minister.

Gyawali suggests it would have been better to form a Government Reform Committee, similar to the High-level Economic Reforms Commission, and appoint someone from outside the government to lead it. “The inputs of such a body might have been more credible and impactful,” he says.

A few months ago, the government formed an Economic Reforms Commission under the leadership of former finance secretary Rameshore Khanal to recommend ways to improve the country’s economy. The commission submitted its report to the government last month. The inputs of the commission, according to officials, were accommodated while preparing the government’s policies and programmes for the upcoming fiscal year.

9.12°C Kathmandu

9.12°C Kathmandu