National

The bill that was and the bill this is

What did King Birendra do with the bill to amend Citizenship Act 1964 that became a topic of discussion after President Bhandari returned the bill to amend Citizenship Act 2006?

Tika R Pradhan & Tufan Neupane

Days after President Bidya Devi Bhandari returned the bill to amend Citizenship Act 2006 with a 15-point message, the House of Representatives on Thursday passed the bill in the existing form. Once the National Assembly passes the bill, it will be sent back to the President again for authentication. This time, the President will have to authenticate it within 15 days from the date of receiving it as per the constitutional provisions.

The President’s move of returning the bill left politicians divided, with those from the ruling parties taking exception to it while those from the opposition hailing the action.

There, however, is no denying that the President exercised her constitutional powers to return the bill. One key issue, however, got buried in the political brouhaha.

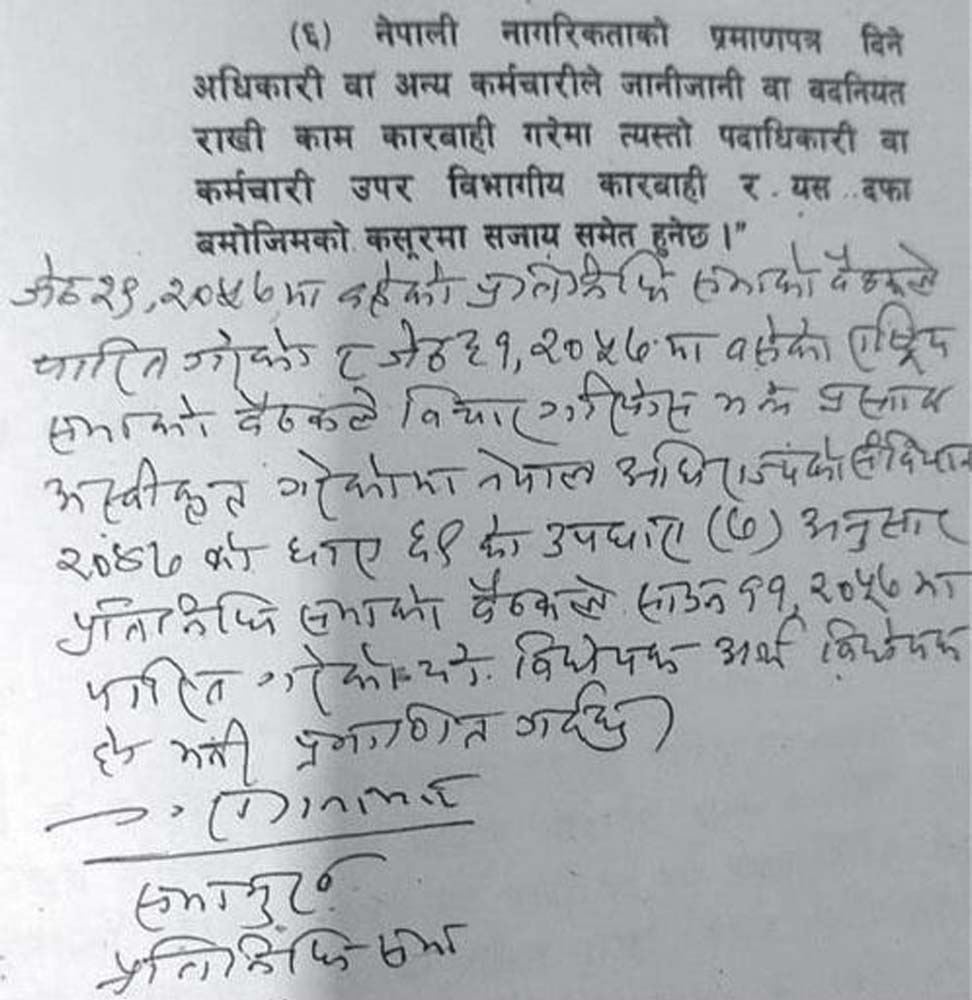

While returning the bill, the President called on the House of Representatives to take a historical overview of issues surrounding citizenship and reminded lawmakers of an incident from 2000. She referred to the amendment bill to the Citizenship Act 1964, which was passed by the lower house on June 11, 2000 but was rejected by the upper house on June 13 that year. The lower house, however, rejected the upper house proposal for a review on July 26.

It is known to all that the bill failed to take the form of an Act, the President said in her message to the House.

The Post inquired with the Parliament Secretariat about the incident. Officials said they had no documents regarding that amendment bill.

“We have long been trying to locate the documents but haven’t found them,” Narayan Dhakal, chief at the bills section of the secretariat, told the Post.

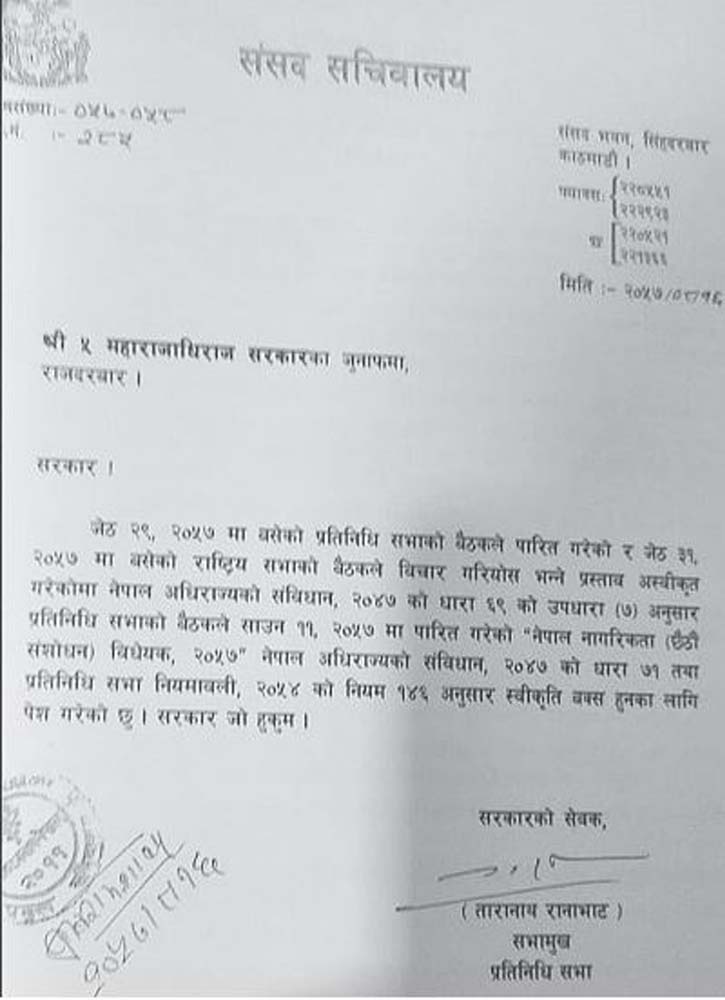

Some documents that are available, however, show that then Speaker Taranath Ranabhat had certified the citizenship bill as a “money bill,” and he had sent the bill to King Birendra—the then head of the state— for authentication on December 1, 2000.

When the Post reached out to Ranabhat, he said he could not exactly recall the incident and that there must have been some circumstances that prompted him to certify the citizenship amendment bill as a “money bill.”

But why would the Speaker certify any other bill as a “money bill”? And why did the bill in 2000 fail to take the form of an Act?

In interviews with the Post, experts and officials called it one of the many idiosyncrasies of the parliamentary system, saying that such practices happen in other democracies too.

What is a money bill?

A money bill is defined by Article 110 (3) as matters concerning imposition, collection, abolition, remission, alteration or regulation of taxes, among others. Article 68 (3) of the 1990 Constitution also had a similar definition for the bill.

The peculiarity of the money bill is that it needs to be introduced only in the lower house and there is no upper house veto on it—it is deemed passed by both the houses if it's endorsed by the lower house—and it cannot be returned by the head of state.

A statement issued by the Office of the President on Sunday said: “The President has sent the Citizenship Act amendment bill to the House of Representatives as per Article 113(3) of the constitution, along with a message that it needs a review.”

Article 113(3) says: “In case the President is of the opinion that any Bill, except a Money Bill, presented for authentication needs reconsideration, he or she may, within 15 days from the date of submission of such Bill, send back the Bill along with his or her message to the House in which the Bill originated.”

Radheshyam Adhikari, an advocate, two-time member of the Constituent Assembly and former National Assembly member, said the parliamentarians in 1990 appear to have misused the constitutional provision so as to ensure that the king did not return the bill.

“As far as my memory serves me right, King Birendra didn’t return the bill, or let’s say there was no message from the palace regarding the bill,” Adhikari told the Post. “Nonetheless, a citizenship bill, or any other bill, should not be certified as a money bill.”

Ranabhat, however, said that any bill involving tax, fine or any financial issues could be certified as a money bill. “You should better ask the general secretary of the Parliament Secretariat, he could explain it better,” he told the Post.

Mukunda Sharma, a former secretary at the Parliament Secretariat, told the Post that there was a tendency to certify most of the bills as a money bill.

“There was a trend in the 1990s to certify any bill that involved even a single rupee of fine or tax as a money bill so that the upper house did not have a veto on it,” said Sharma. “That could be the reason the citizenship amendment bill must have been certified as a money bill.”

After the restoration of democracy in 1990, the king became a constitutional monarch, but the upper house continued to have the majority of members from the palace.

“It was a tactical move to nullify the role of the national assembly,” Sharma told the Post. “The Speaker’s role hence became powerful.”

According to Sharma, discussions were also held over whether every other bill should be introduced as and certified as a money bill.

Both the 1990 Constitution and the 2015 Constitution have similar provisions regarding a money bill, except for one addition in the 2015 charter—“provided that any bill shall not be deemed to be a Money Bill only by the reason that it provides for the levying of any charges, fees or tariff such as licence fee, application fee, renewal fee or for the imposition of fines or penalty of imprisonment.”

Article 68 (4) of the 1990 Constitution says: “If any question arises whether a bill is a money bill or not, the decision of the Speaker shall be final.” This provision has been retained in the 2015 Constitution as well.

The Post could not independently verify if any controversy had arisen in 2000 on whether the citizenship bill was a money bill or not.

People familiar with the matter in 2000 say the king had held consultations with the Supreme Court but they could not exactly say what followed. The 1990 Constitution allowed the king such consultations. Article 88 (5) of the 1990 Constitution says: “If His Majesty wishes to have an opinion of the Supreme Court on any complicated legal question of interpretation of this constitution or of any other law, the court shall, upon consideration on the question, report to His Majesty its opinion thereon.”

Badri Bahadur Karki, a senior advocate who was the attorney general at that time, said King Birendra had sought the opinion of the Supreme Court.

"The Supreme Court used to conduct hearings on issues on which the king sought the court’s opinion," Karki told the Post. "I can't remember who participated in the hearing then and what all happened."

The provision that a money bill cannot be returned by the President for a review is in the Indian constitution as well.

Article 111 of the Indian constitution says that the President may return any bill, if it is not a money bill, to the Parliament for a review. If the bill is passed again by the Houses with or without amendment and presented to the President for assent, the President shall not withhold assent therefrom, the Indian constitution says.

The Indian government in 2016 had introduced the Aadhaar Bill as a money bill in the Lok Sabha (lower house). It was endorsed as the Bharatiya Janata Party enjoyed a majority. But it led to a row. The opposition didn’t agree with the government’s classification of the Aadhaar Bill as a money bill, in which the Rajya Sabha (upper house) has no power to veto. In 2018, a five-judge Supreme Court bench held its constitutional validity.

The question, however, remains why the constitution empowers the Speaker to certify any bill as money bill, and why is there another provision that says “the President can return any other bill except the money bill to the Parliament for a review.”

Rameshore Khanal, a former finance secretary, said such provisions are put in the constitution so as to rescue the governments during difficulties. “The problem is politicians tend to ignore the good intent of the provision and misuse it for their political interests,” Khanal told the Post.

Khanal offered the example of the ordinance provision.

“Ordinances have been provisioned in the constitution with good intent. Who had imagined the provision of ordinance would be misused,” Khanal told the Post. “Both KP Oli and Sher Bahadur Deuba misused it for their petty interests.”

Back to the money bill.

Since there is no constitutional provision for the President to return the money bill because such a bill is introduced to the lower house with prior notice to the President, the President has no option but to authenticate it. But what happens when any bill certified by the Speaker as a money bill is sent to the head of state for authentication and the head of state does not agree with it or its provisions?

Nothing has been specified in the constitution about it.

Since there’s no provision of returning, the President may not act—won’t authenticate it, leading to automatic termination of the bill. Since no documents are available relating to the citizenship bill amendment case of 2000, the general assumption is the king didn’t act on it—and it lapsed.

The last amendment to the Citizenship Act 1964 was made on May 30, 1991. In 2006, a new law was enacted for amendment and integration of matters relating to the Nepal Citizenship Act.

A bill to amend the Citizenship Act 2006 was introduced in the House on August 7, 2018. The State Affairs and Good Governance Committee deliberated on it for 22 months before sending it to the House. But the Sher Bahadur Deuba government earlier last month withdrew the old bill and introduced a new amendment bill, which was passed by the lower house on July 22 and the upper house on July 26.

After the passage of the bill by the lower house on Thursday, it is set to be sent to the President soon.

The President now will be left with no option than to authenticate it because she is bound by the constitution.

“In case any bill is sent back along with a message by the President, and both houses reconsider and adopt such a bill as it was or with amendments and present it again, the President shall authenticate that bill within 15 days of such presentation,” says Article 113(4).

(Binod Ghimire contributed reporting.)

16.12°C Kathmandu

16.12°C Kathmandu