National

Status of those disappeared during insurgency continues to elude families

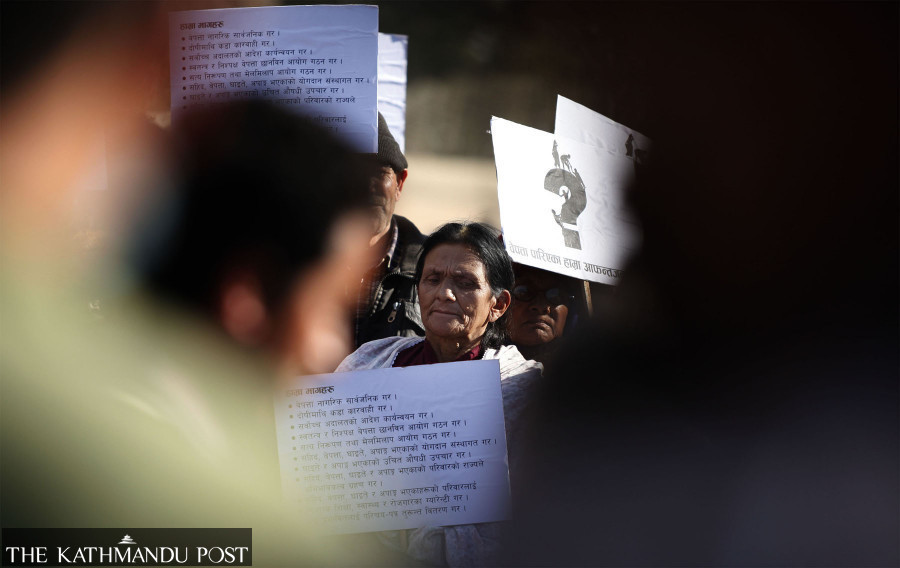

Conflict victims are not hopeful of the government’s latest plan to conclude the transitional justice process.

Binod Ghimire

Ganesh KC was just thirteen when he joined the Maoist rebellion.

The year was 2001 and the teenager had returned home for vacation from New Delhi, India when a cultural team of the CPN (Maoist) wooed him into joining them.

Being of an impressionable age, Ganesh agreed to join the Maoists and left his home at Jaimini, Baglung.

On November 28, 2001, Ganesh was arrested when he and his fellow comrades encountered a patrol team of the then Royal Nepal Army.

While the other senior members of his group managed to flee, Ganesh could not.

For the next few months, the Army reportedly used Ganesh to spy on the Maoists and their sympathisers. And then he disappeared.

Ganesh’s father Bimal has been searching for the whereabouts of his missing son ever since.

“When I visited the district battalion of the Army to inquire about my son’s whereabouts, I was directed to the Western Division of the Army in Pokhara,” Bimal said on the eve of the International Day of the Disappeared, which is observed every year on August 30.

“I then travelled to Pokhara, but I was told that the district battalion should know where my son is,” said Bimal over the phone from Baglung.

This back and forth continued for a long time without any progress.

“I think it was their [Army] strategy to tire me,” Bimal said.

Bimal, who used to work in New Delhi, quit his job to search for his missing son. His search continues even today.

“I’ve a feeling that my son will return home one day,” he said.

Parshuram Koirala from Thakre Rural Municipality in Dhading has a similar story.

On the night of December 14, 2003, three Maoist combatants took away his wife Goma. Parshuram was told by the Maoists that they would return Goma home safely after asking her some questions.

“I knew one of the Maoist fighters because he had stayed in our house on many occasions,” Parshuram said. “I had suspected something was wrong but I didn’t believe they would disappear her.”

It's been 18 years since Parshuram and his family have been searching for Goma’s whereabouts.

“Some say she was killed for spying on the Maoists. If that’s true, I demand to see her body,” Parshuram said. “I can name the three persons who abducted her. Book them as per the law. Is it that complicated?”

Ganesh and Goma are among the hundreds of individuals who were disappeared by the Maoists and the state security forces during the decade-long insurgency, in which more than 13,000 people lost their lives.

The Maoists laid down their arms and officially joined peaceful politics with the signing of the Comprehensive Peace Agreement on November 21, 2006.

The agreement stipulated that both sides—the state and the Maoists—would make public, within 60 days of signing the deal, the information including the real names, castes, and addresses of the people who disappeared or were killed during the insurgency, and inform the victims’ family members.

Both the parties have failed to abide by the deal.

Except for forming the disappearance commission and providing some compensation, the state has done little to find out the fate of the disappeared persons.

In its six years of formation, the commission has received 3,223 complaints of enforced disappearance perpetrated both by the security forces and the Maoists. After looking into the complaints, the commission has identified 2,494 cases as genuine.

The latest report by the International Committee of the Red Cross, however, says 1,333 people are still missing in connection with the armed conflict.

The victim families whose members have disappeared have each been provided Rs1 million in compensation but not all have received the amount. The report of the disappearance commission shows only 1,227 such families have received the compensation.

“We have recommended that the government provide compensation to the remaining families and provide additional government benefits to those who have received identity cards issued by the commission,” Sunil Ranjan Singh, a member of the commission, told the Post. “We are preparing to carry out exhumation in a few places and start taking statements from the alleged perpetrators within a couple of months.”

Officials at the commission say as the government’s common minimum programme aims to conclude the remaining tasks of the peace process by expediting the transitional justice process, they expect that the long overdue revision of the Enforced Disappearances Enquiry, Truth and Reconciliation Commission Act, 2014 will be made.

The Supreme Court in February 2015 had directed the government to amend around a dozen amnesty-related provisions in the Act.

The conflict victims, however, aren’t hopeful.

“The incumbent government hasn’t consulted us nor is it interested in it. The common minimum programme mentioned the issue just to show it to the world,” Suman Adhikari, former chair of Conflict Victims Common Platform, said. “This government will do nothing in our favour.”

16.73°C Kathmandu

16.73°C Kathmandu