Miscellaneous

The First Map of Nepal

The 1802 British expedition to Nepal by surgeon-naturalist Francis Buchanan-Hamilton was seminal for two reasons—it introduced 1,100 species of plants to the world of botany and it gave the world the very first scientific map of Nepal.

Sanyukta Shrestha

The 1802 British expedition to Nepal by surgeon-naturalist Francis Buchanan-Hamilton was seminal for two reasons—it introduced 1,100 species of plants to the world of botany and it gave the world the very first scientific map of Nepal.

This, however, was not the first British foray into Nepali territory. While we have completed 200 years of Nepal-Britain relationship this year, records show that the British had attempted to set up bilateral relationship with Nepal at least four times prior to Buchanan-Hamilton’s expedition. The first ever attempt was by Captain George Kinloch’s troop marching via the Tarai, in 1767, to help king Jaya Prakash Malla defend his Kathmandu throne against the Gorkhali invasion. Kinloch’s travelogue from 26th August to 17th October in his diary, archived at the British Library, remains one of the most dramatic expeditions to Nepal in known history.

In his own words, Kinloch’s troop faced adverse weather conditions and had so little food to eat that they eventually had to retreat before they went anywhere close to Kathmandu Valley. This circumstantial retreat was quickly fabricated by the Gorkhali contingent as a victorious rout. But the fact remains that the British were never truly interested in northern Nepal, due to potential conflict it would invite at the Chinese frontier and the additional resources it would drain from East India Company. Maintained till the end, their interest was largely limited to the fertile lands of the Tarai. Once their plan to ally with Kathmandu’s Malla kings proved to be unrealistic, the British quickly switched to conciliatory policy with the Gorkhali new order.

Execution of this new British policy with Nepal started with James Logan’s mission in 1770, then Foxcroft’s mission in 1784 and finally Kirkpatrick’s oft-cited expedition in 1793. All these missions, however, failed miserably. While Kirkpatrick managed to introduce Nepal to Britain, and the world at large, through his seminal book in 1811, he actually failed to set up a British residency in Kathmandu as he had initially set out to do. Known the world over for their diplomacy, the ultimate mission of the British was not to be realised until Francis Buchanan-Hamilton travelled to Kathmandu, putting together the first map of Nepal in the process.

Buchanan-Hamilton’s expedition started from Patna on 12th January, 1802, and camping further along the Indian border at Gorasan and Chucheroa until mid-March, he first entered Nepali territory at Gor Pursera on 29th March. Already at Hettaura (Hetauda) by the end of March, he travelled past Bhimphedi, Chitlong, Panouny, and Tancot, before camping at Suembu (Swoyambhu) for a little more than three months. Eventually, he was moved to a home near Narainhutty (NarayanHiti) temple with Captain Knox on 26th July 1802, setting up the first British residence in the Capital.

En route to Kathmandu, Buchanan-Hamilton made the best use of his botanical expertise by documenting 1,100 plant species from Nepal, alongside 110 paintings by a Bengali artist who might have accompanied him from Patna. Most of these floral species are already in an endangered state in Nepal, as they are either over-consumed for medicinal use or have fallen prey of the changing climate and habitat of the Himalayan region. Considered as ‘Father of Nepali botany’, there are those that believe Buchanan-Hamilton initially produced his maps to locate Nepal’s floral distribution.

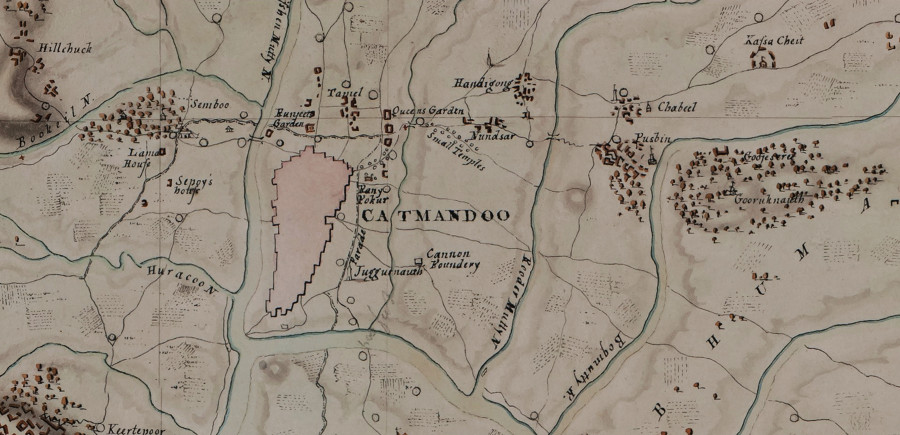

There are a total of three maps at the Linnean Society of London, and a set of copies signed by Major Charles Crawford—a companion of Buchanan-Hamilton during the expedition—at the British Library too. The smallest one among these, 76 x 72 cm, is also the only coloured piece. With the most detailed view of Kathmandu Valley scaled down to 1¼ inches to a mile, it is titled “Map of the Valley of Nepaul,” referring to the then Nepal proper or the Kathmandu Valley. The significance of this map can be valued for its potential to support our understanding of Kathmandu’s early settlements, heritage sites and some of the forgotten nomenclature as well.

The map includes two places labelled “Chounga Narain”. One is to the northwest of Bhaktapur where we would normally expect the present day Changunarayan Temple. The other is midway between Semboo (Swoyambhu) and Nagarjoon (Nagarjun), which is potentially the mislabeling of the present-day Ichangunarayan temple. What also appears twice in his map is Sanghoo. The first label is eastward from Vajrayogini, where we would normally expect Sankhu in a contemporary map. Then again southeast from Bhaktapur Kutunja (Katunjay), appears another Sunghoo which most probably is present-day Sanga misspelt.

With his Scottish accent and newly-learnt Bengali, Buchanan-Hamilton took up Sankhu as Sanghoo and Vajrajogini as Bujjer Jogunee. To the northwest of Bhatgong (Bhaktpur), he clearly lines up the towns of Bhoreh (Boday), Nugdhes (Nagadesh), and Themee (Thimi) almost along the same longitude. While not all of our inferences from these maps can be as useful due to his language limitations, the solid spatial placement of labels are indeed effective in fitting various missing pieces from the historic jigsaw of the lesser-documented Kathmandu.

Among his errors, some of which stick out as a sore thumb, are malformed conjuncts like Boorah Leel Kunt for Budhanilkantha. This further misleads him to write Leel Kunt temple further down the southwest, which can actually be the Nilkuntha temple of today. An instance like Gudoulee for Godavari could be less of his own error, since the resident Newars’ tongue is well accustomed to replacing an “R” sound with an “L” sound. Others, like Soonagooly to the west from Harisidee (Harisiddhi) also hints towards any earlier form of present-day Sunakothi. Further south from Harisiddhi, instances like Thyboo, Pinoutee, and Thauncote could also very well be local dialect for what is today known as Thaiba(h), Panauti, and Thankot respectively.

The other two maps in this set are wider, 128 x 76 cm each, and monochrome. One of them is titled “Map of the Route of Nepaul” and its scale is not defined. The third map lacks a title and is scaled down to five inches to a degree. These two maps attempt to project the boundaries of the Gorkha expansion, which was at its peak, under the brand name of Nepal, through the eyes of a small team from the full-blown British Empire that had already taken shape. Buchanan-Hamilton’s route to Catmandoo (Kathmandu) clearly marks Goorca (Gorkha) to the west, alongside Pokhra (Pokhara) and further to MukteeNauth (Muktinath) to the far northwest. The dominion of Nepal is clearly shown from near Hurryduar (Haridwar) on the Ganges, to the Teesta, together with the bordering parts of Tibet and Gorwhal. While places like Delollgaut (Dolalghat) are labelled in the east, clearly marked in the south is Bettiah from where the expedition entered Nepal.

Drawn by Major Charles Crawford, the most reliable testimony for the making of the maps is Buchanan-Hamilton’s book from 1819 titled An Account of the Kingdom of Nepal and the Territories Annexed to the Dominion by the House of Gorkha. However, the British Library’s India section has an unpublished manuscript Some Observations on Nepal, also by Buchanan-Hamilton. Dated 1802 on its cover page, Buchanan-Hamilton seems to have drafted much of the initial text during his expedition itself. Same can be estimated about when maps were drawn.

Interestingly, Buchanan-Hamilton has addressed the mountain Hindus as Parbatiyas, much like what the Kathmandu Newars do till date, and their language as Parbatiya bhasha, or Khas bhasha as it was popularly known to the west from the Capital. As a critical observer, he found Khas bhasha rapidly progressing to an extent of ‘extinguishing the aboriginal dialects of the mountains,’ which today is already a harsh reality. He further made notes of the Nepali word for neighbouring British territory as Mogulany, and the southern plain as Terriany. While he is assured that Mogulany is after its former Lords or the Moghul emperors, it also goes well with what we call Muglan today.

Throughout the introduction of his book, Buchanan-Hamilton has credited a number of local informants for his maps of Nepal. Eight of his principal consultants were, namely, the Kirat chief Agam Singha, a Brahmin from Bahadurgunj, Narayan Das from Lohanga, a slave of the Gorkha King, a Kirat from Hedang near Arun River, the royal priest of Palpa named Sadhu Ram Upadhaya, businessman Kanak Nidhi Tiwari from Kumaun, and Samar Bahadur, the uncle to the king of Palpa. The above ensemble speaks volumes for the hard work put together by Buchanan-Hamilton and Crawford to come up with their cartographical masterpiece on Nepal.

Easily invading smaller and less powerful kingdoms around it, Gorkha expansion was soon approaching the British dominion to the south and Tibetan highlands to the north at the time. Had it not been for the Papers Respecting the Nepaul War published from New Delhi in 1983, we would have never been able to relate these maps as confidently to the real purpose for which they were drawn or at least later utilised.

Hundreds of messages corresponded between various officers of the British Raj are cited in this compilation running 998 pages. On page 37 is a letter signed on 19th August 1814 by Dr Buchanan. He is none other than surgeon Francis who later changed his surname to Hamilton for inheritance purposes. Addressed to John Adam, the secretary to the British Government, Buchanan-Hamilton writes around 38 long paragraphs to communicate a great deal of military advice aimed at the ultimate invasion of Nepal. He also starts the second paragraph with a mention of his maps.

Later, on September 9, Adam is seen replying Buchanan-Hamilton to convey his Governor-General’s acknowledgement for the receipt of his maps, and claims his advice as ‘the greatest utility in framing the system of operations to be undertaken against the Nepaulese’. Moreover, a simple comparison between Buchanan-Hamilton’s original 1802 manuscript and his reworked 1819 publication makes it crystal clear that his intention was to keep the purpose of his expedition a secret. Alongside deleting the names of his expedition members here and there, he seems to be carefully omitting sensitive information on Nepali territory that was aimed at assisting military operations by the British. Throughout his career with the Company, Buchanan-Hamilton seems to have been successful in keeping all of his extended strategic programmes a secret within his confidential letters to the British Government.

Finally, Secretary Adam’s letter dated 2nd November 1814 from camp Bareilly is addressed to the Magistrate of Rungpore, David Scott. In this detailed correspondence conveying the Governor-General’s instruction to negotiate with Nepal for a Treaty of Peace, he seeks the independence of Sikkim from the Gorkhalis. A 15- paragraph long extract from the Buchanan-Hamilton’s initial report is also enclosed as an authorised declaration.

Beyond this point, we do not know if Hamilton’s maps were of any further use during the Anglo-Nepali war leading to the Sugauli Treaty of 1816 that ceded a third of Nepal’s territory to the British. What we know is that the British invasion of Nepal remained an unfulfilled dream, and there is so much to learn from the first maps of Nepal drawn by them.

The maps are incidentally on sale at the Linnean Society of London for a relatively measly sum of £21,000; maybe it would be a good fit in a museum in Nepal?

(All photographs are from the permission of The Linnean Society of London.)

The author is a researcher of Nepali art history and a software developer based out of London, UK

12.47°C Kathmandu

12.47°C Kathmandu