Columns

The great divide

It is distressing to see boys sent to private schools while their sisters attend public ones.

Deepak Thapa

It was in the early 1990s that, for the want of anything better to do at a family function, I had picked up the school magazine of a younger relative whose house we were at. She went to one of those places that was well known at one point but has since lost its sheen. What astounded (and infuriated) me was that the main story in an annual publication meant to showcase students’ academic and extra-curricular activities was a recounting of the principal-cum-owner’s family vacation in the United States, complete with photos taken in a few key locations.

Mind you, this was long before itinerant and ubiquitous Nepalis had made it nothing out of the ordinary to hear Nepali spoken in almost every major city in the West. Nepal was still quite a poor country, and travelling for fun to places like the US was almost unheard of among the middle class to which the owner of the school squarely belonged. The only difference was that a few years earlier, he and his family had started a school that had rapidly gained fame in the still quite-uncrowded field in Kathmandu as well as in Nepal generally. One upshot of getting into the education business was that within years, they had the moolah for the American sojourn.

Such stories are legion across Nepal. One can only surmise that this is why there has been little more than studied disinterest in the protest programmes announced by the private schools against the proposed School Education Bill that is finally wending its way through parliament. Equally unconvincing to the general public would be that the main bone of contention of the private schools has all to do with money matters and nothing more. Perhaps aware of the tremendous political clout the private education sector has—and can wield—all the major student unions have banded together to call on the government to go take even more drastic steps to reduce the role of the private players in education. How these contradictory demands and those of other interest groups will play out in the legislative process will be interesting to observe in the coming weeks and months.

Meanwhile, we can look at the current role of private schools in education in Nepal. But first, a slight detour to delve into the past.

It may have slipped the notice of many, but the one big change over the years vis-à-vis private schools is that fewer people refer to them as ‘boarding schools’, or simply ‘boarding’. This conflation of private schools with those with dormitories for boarding students came about thanks mainly to the missionary school, St Xavier’s (and, later, St Mary’s) and Pharping Boarding School (now called Tribhuvan Adarsha Awasiya Madhyamik Vidyalaya), both established in 1951. These early pioneers, and a few others set up along similar lines, had laid the groundwork for a market for English-medium education.

The private sector received a fillip following the introduction in 1973 of the New Education Plan, which categorically stated that Nepali would be the language of instruction in schools thenceforth. The growing middle class would not have it and began looking at the non-government sector to fulfil their need for English-medium schools. Thus began the ‘boarding school’ phenomenon that spread across Nepal within a matter of a decade or so, and the concomitant downward slide of government schools.

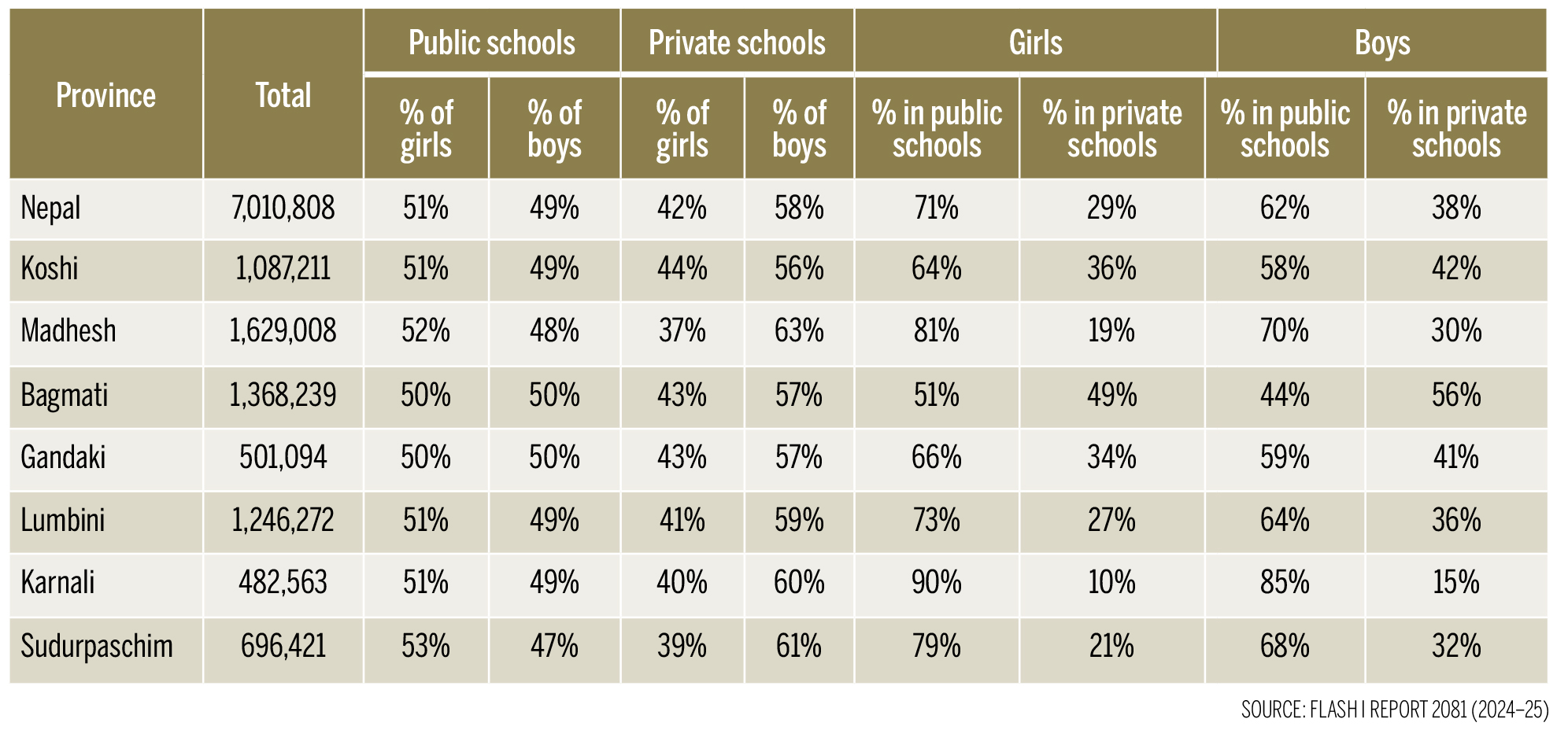

According to the latest government statistics, there are currently over 35,000 schools in Nepal. Of these, 77 percent are ‘community and religious schools’, as the government/public schools are known formally, and 23 percent are private schools, ‘institutional schools’ in official parlance. The latter includes schools owned privately or by a trust or some such entity, and number more than 8,000, certainly not a small number at all. In fact, the proportion of students in these institutions is comparatively higher. Of the total 7 million school students in the country, 4.6 million study in public schools and 2.4 million in private schools, with the latter number representing 34 percent of the students. That is only to be expected though since government schools continue to operate in the most far-flung places, sometimes catering to just a few students, unlike the private ones that are concentrated in urban areas and market centres.

That students from private schools perform much better than those from government schools is well known. As has often been pointed out, this happens even though government schoolteachers are generally paid more and enjoy better facilities, including job security. This seeming anomaly does not consider factors such as the economic background of those who attend private schools, along with motivational attitudes of parents and families and a conducive home environment, among many others that contribute to the well-being of students. Whereas government schools usually contend with forced and casual truancy, poor quality textbooks (if they arrive in time), large student-to-teacher ratios, political interference, and so on.

The fact remains that private schools are often the first choice of those who can afford it. That is why it is even more distressing to look at the gender disparity that remains, with boys sent to private schools while their sisters attend public ones. The Nepal average shows 38 percent of the male students in private schools as opposed to 29 percent of the female student body. And it cuts across all the provinces, even though the contrast is sharper in some provinces compared to others.

One way the gap could be bridged is by private schools proactively fulfilling the proposed law’s scholarship mandate towards that end should that provision be retained. They could even go a step further to reduce caste/ethnic differences as well. For some inexplicable reasons, official reports discuss only the attendance of students from ‘Dalit and Janajati communities’ and ‘22 disadvantaged Janajati communities’ and without any elaboration on the type of school they attend. The government could easily provide data on all caste/ethnic groups, which private schools could make use of to bring about equitable outcomes for our young ones.

But that might be too much of an ask. I could be wrong, but I know of no occasion when private school groups have come together for something other than what affects their pocketbooks. For instance, I am not aware of any group or groups of schools demanding at any time that textbooks approved for use in class meet some kind of standard, whether in terms of language, content or production quality. That could be just one way of demonstrating that their interest also lies in the welfare of their students.

20.9°C Kathmandu

20.9°C Kathmandu