Columns

Football takes capitalism out of bounds

With a red card shown to the moguls, the time may have come for a broader rethink of who owns what.

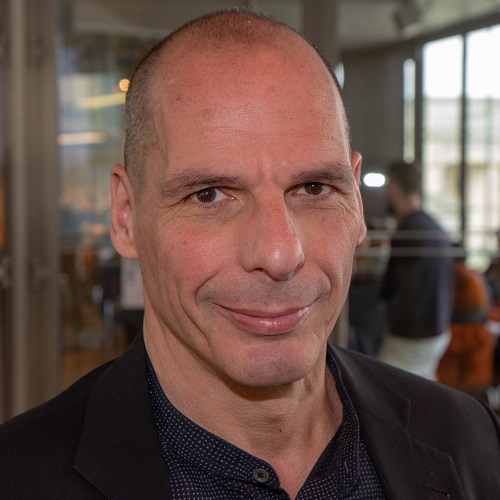

Yanis Varoufakis

Europe has discovered its moral Rubicon, the frontier beyond which commodification becomes intolerable. The line in the sand that Europeans refuse to cross, come what may, has just been drawn.

We bowed to bankers who almost blew up capitalism, bailing them out at the expense of our weakest citizens. We turned a blind eye to wholesale corporate tax evasion and fire sales of public assets. We accepted as natural the impoverishment of public health and education systems, the despair of workers on zero-hour contracts, soup kitchens, home evictions, and mind-numbing levels of inequality. We stood by as our democracies were hijacked and Big Tech stripped us of our privacy. All of this we could stomach.

But a plan that would end football as we know it? Never.

Last week, Europeans showed the red card to the moguls—and their financiers—who tried to steal the beautiful game. A potent coalition of conservatives, leftists, and nationalists, uniting Europe’s north and south, rose up in opposition to a secret deal by the owners of many of the continent’s richest football clubs to form a so-called Super League. To the owners—including a Russian oligarch, an Arab royal, a Chinese retail magnate, and three American sports potentates—the move made obvious financial sense. But from the perspective of the European public, it was the last straw.

Last season, 32 clubs qualified to play in Europe’s Champions League, sharing €2 billion ($2.4 billion) in revenues from television rights. But half of the clubs, teams like Real Madrid and Liverpool, attracted the bulk of the European television audiences. Their owners could see that the pie would increase substantially by scheduling more derbies between the likes of Liverpool and Real Madrid, rather than matches featuring lowly sides from Greece, Switzerland, and Slovakia.

And so it was that the Super League proposal was hatched. Instead of sharing €2 billion between 32 clubs, the top 15 clubs calculated they could divide €4 billion among themselves. Moreover, by creating a closed shop, with the same clubs every year, regardless of how well they perform in their national championships, the Super League would remove the colossal financial risk that all clubs face today: failing to qualify for next year’s Champions League.

From a financier’s perspective, kicking out the laggards and forming a closed cartel was the logical next step in a process of commodification that began long ago. Here was a deal that would quadruple future income streams and remove risk by turning those streams into a securitised asset. Is it any wonder that JPMorgan Chase rushed in to finance the deal with a golden-handshake offer of €300 million to each of the 15 clubs that agreed to leave the Champions League behind?

Whereas the Brexit saga lasted years, this particular breakaway attempt collapsed within two days. Whatever the financial logic behind the Super League, its plotters had failed to consider an intangible yet irresistible force: the widespread conviction among fans, players, coaches, communities, and entire societies that they, not the tycoons, were the true owners of Liverpool, Juventus, Barcelona, and the rest.

And who could blame the owners for not seeing it coming? No one protested when they floated their clubs’ shares on stock exchanges alongside McDonald’s and Barclays. For years, fans watched passively as oligarchs poured billions into a few leading clubs, killing off all real competition by packing their rosters with the world’s great players.

But while the European public could tolerate that the probability of a laggard ever winning anything had fallen close to zero, the Super League would officially take that chance the rest of the way. Maximising profits would now mean the formal extinction of the possibility even to dream that a lowly team like Stoke City or Athens’ Panionios could one day win the Champions League. The complete elimination of hope, however distant capitalism had rendered it, provided the spark that stopped football’s oligarchy in its tracks.

Meanwhile, in the United States, even cynical sports moguls understand that free-market capitalism chokes competition. The US National Football League is a paragon of aggressive competitiveness, and not only because super-fit players sacrifice their health for wealth, acclaim, and a shot at Super Bowl glory. The NFL is competitive because it imposes on its teams a strict salary cap, while the weakest are guaranteed their pick of the best rookie players. American capitalism sacrificed the free market to save competition, minimise predictability, and maximise excitement. Central planning lives in sin with unbridled competition—directly under the spotlight of American show business.

If the objective is an exciting, financially sustainable football league, the American model is what Europe needs. But if Europeans are serious about their claim that the clubs ought to belong to the fans, players, and communities from which they draw support, they should demand that clubs’ shares be removed from the stock exchange and the principle of one member-one share-one vote is enshrined into law.

The crucial question of whether the oligarchy should be regulated or dismantled extends well beyond sports. Will US President Joe Biden’s spending and regulation agenda suffice to rein in the unbridled power of the few to destroy the prospects of the many? Or does genuine reform demand a radical rethink of who owns what?

Now that Europeans discovered their moral Rubicon, the time may have come for a broader rebellion that vindicates Bill Shankly, the legendary Liverpool manager and staunch socialist. 'Some people believe football is a matter of life and death,' Shankly famously said. 'I can assure you it is much, much more important than that.'

—Project Syndicate

22.68°C Kathmandu

22.68°C Kathmandu